SoFloPoJo

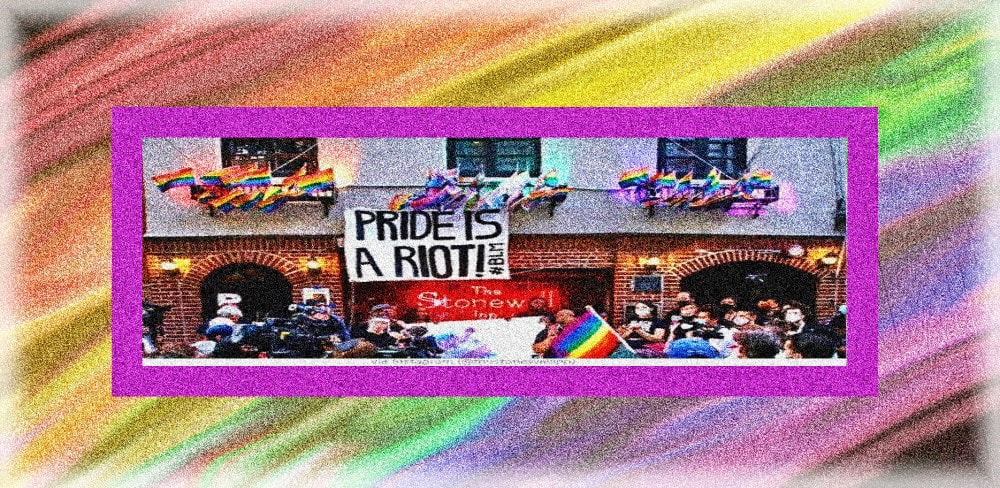

JUST SAY GAY

Poetry, Prose, Pictures & Rants

in Response to the homophobia

exhibited by Florida's "anti-Woke"

elected officials

Poetry, Prose, Pictures & Rants

in Response to the homophobia

exhibited by Florida's "anti-Woke"

elected officials

Lorelei Bacht. Fadrian Bartley. Robert Carr. James Champion. Casey Charles. Acadia Currah. Ace Englehart. Nathaniel Farcas. Robin Gow. Caroline Hayduk. A.E. Hines. SG Huerta. Judy Ireland. Andie Jones. Paige Justice. Ben Kline. Koss. Danielle Lemay. Jason Masino. Bryan Monte. Michael Montlack. Kyrsta Moorehouse. F.M. Nicholson. Dion O'Reilly. Kenneth Pobo. David P. Prather. Carrie Magness Radna. Sam Runge. G.J. Sanford. Gregg Shapiro. Alison Stone. Laurie Rachkus Uttich. Keagan Wheat. Cassandra Whittaker.

Lorelei Bacht

molluscan seashells

i have an idea: enter this roofless room,

colour-wash every wall

with surprises: peony tongue, orange

vault of the mouth. leave blame

in the locker. travel and lose

the ticket in the dunes. make a comprehensive

list: indifferences, potentials and

sanctimonies. every goddamned bullet

point. eat it. a group of nudibranchs

is called a decision. forget your 80s

power suit. come be: soft-bodied clown,

marigold, splendid and dancer.

Lorelei Bacht's poetic work has appeared/is forthcoming

in The Night Heron Barks, Queerlings, Barrelhouse, Sinking City,

Stoneboat, streetcake, and elsewhere. They can be found on Twitter

@bachtlorelei and on Instagram @lorelei.bacht.writer. They are currently

watching the rain instead of working on a chapbook.

|

Fadrian Bartley

No Skin is Too Thick Let us hold men in our hands to feel their rough edges between our fingers, and massage their temper before we misunderstand. Let us have them sit on balconies and submit to our attentions and call those moments the vibes, so their inner voice will speak through cigarettes and the smells of intoxicated pores through thick skins. Let us speak to them in silence, since they already know the meaning of that word, but not in the shape and form of poetry. Let them know that giants cannot crush the rain with bare hands, or sweep away the river with their lashes. Let them know that it is ok to empty the soul in front of the universe for all to see, and release the clogged tunnel in their veins. Let them know that petals bleed when no one is looking, but birds and butterfly will know. |

Fadrian Bartley is a Jamaican writer and is the author of family curses. His poetry is available in a few online web magazines which include, IHRAF- International Human Rights Art Festival. Mixedmag.co, Pif-magazine, Aphelion, and platforms such as allpoetry.com. Fadrian has a NVQJ diploma in customer relations, and his writing focuses on life, nature, and people’s personality. His inspiration comes from within and continuously opening new pages to begin new chapter.

Robert Carr

A Day Without Trousers

To be something pretty, to scratch

the clothes you think I am, drop pants and wrap

in Sri Lankan sarongs I ordered on Amazon.

To step proudly in my prissy garden,

obsessed with floral perfections,

petaled geometries, squeal in heat when groundhogs

strip leaves from the coneflower.

To holler – The flowers! and mean every tooth,

spit back at neighbors who roll their eyes.

To catch and release the most beastly things,

to bawl on the lawn, curse my failed Hav-a-Hart

Trap, attend to the dramas of wishbone

and cantaloupe bait. Husband, I dream

furry rodents choking in midnight, perennial

soil transformed to tombstone. Echinacea,

for headaches, for pain, the salmons,

some yellows, the reds. I know grief is tiresome –

You slam doors; drive off to buy poison.

In your eyes, I’m without a stomach

for bullets or the balls to drown vermin.

Diminishing dreams, you taunt my waking

screams, the sound made by whistle pigs.

Let’s have a day without trousers,

roll sheets of fabric low on our hips, bare chested,

dissolve in bright color. How lovely, together,

to shamelessly mince among half-eaten flowers.

Robert Carr is the author of Amaranth, published in 2016 by Indolent Books and

The Unbuttoned Eye, a full-length 2019 collection from 3: A Taos Press. Among other

publications his poetry appears in Crab Orchard Review, Lana Turner Journal,

the Maine Review, the Massachusetts Review and Shenandoah. Selected by the Maine

Writers and Publishers Alliance, he is the recipient of a 2022 artist residency at Monson Arts.

Additional information can be found at robertcarr.org

A Day Without Trousers

To be something pretty, to scratch

the clothes you think I am, drop pants and wrap

in Sri Lankan sarongs I ordered on Amazon.

To step proudly in my prissy garden,

obsessed with floral perfections,

petaled geometries, squeal in heat when groundhogs

strip leaves from the coneflower.

To holler – The flowers! and mean every tooth,

spit back at neighbors who roll their eyes.

To catch and release the most beastly things,

to bawl on the lawn, curse my failed Hav-a-Hart

Trap, attend to the dramas of wishbone

and cantaloupe bait. Husband, I dream

furry rodents choking in midnight, perennial

soil transformed to tombstone. Echinacea,

for headaches, for pain, the salmons,

some yellows, the reds. I know grief is tiresome –

You slam doors; drive off to buy poison.

In your eyes, I’m without a stomach

for bullets or the balls to drown vermin.

Diminishing dreams, you taunt my waking

screams, the sound made by whistle pigs.

Let’s have a day without trousers,

roll sheets of fabric low on our hips, bare chested,

dissolve in bright color. How lovely, together,

to shamelessly mince among half-eaten flowers.

Robert Carr is the author of Amaranth, published in 2016 by Indolent Books and

The Unbuttoned Eye, a full-length 2019 collection from 3: A Taos Press. Among other

publications his poetry appears in Crab Orchard Review, Lana Turner Journal,

the Maine Review, the Massachusetts Review and Shenandoah. Selected by the Maine

Writers and Publishers Alliance, he is the recipient of a 2022 artist residency at Monson Arts.

Additional information can be found at robertcarr.org

James Champion Whitehall, MI

Inventing the Veil

We are making love to ourselves in the dark.

It makes a ghost,

doesn’t it boys. We ignore it as it stalks

us, pacing room to room,

holding ourselves, flickering

in compact

mirrors. No lipstick, no

sticky sentiment. We snap

shut like ungodly clamshells—we’ve

nothing to offer, no pearl

for public viewing.

It is our soul-thing, our opal gleam.

Boys, we must now be precise, undaunted

as the surgeons we really are. Let’s

pull ourselves

on in the woods, like a sheath

of smoke, our strange-sexed nylon stockings.

The mascara of night

applies itself to us. We

blush. It’s a shame.

We really have let it come to this.

The mourning

dove weds our reality to

the morning—

a melodic glue. In the obscene light

we see the results

of our night’s cruel

experiments: bra straps clasped onto

thin air, hacked

Barbie limbs, matte-white ceramic

shards in the ditch, like pieces of destroyed moon.

James Champion (he/him/his) is from Whitehall, Michigan.

He has a bad habit of looking only at his shoes as he walks place to place,

but this makes arrival (and the sky) a constant surprise. You can find him

online at @jameslchampion on Instagram or Twitter.

Inventing the Veil

We are making love to ourselves in the dark.

It makes a ghost,

doesn’t it boys. We ignore it as it stalks

us, pacing room to room,

holding ourselves, flickering

in compact

mirrors. No lipstick, no

sticky sentiment. We snap

shut like ungodly clamshells—we’ve

nothing to offer, no pearl

for public viewing.

It is our soul-thing, our opal gleam.

Boys, we must now be precise, undaunted

as the surgeons we really are. Let’s

pull ourselves

on in the woods, like a sheath

of smoke, our strange-sexed nylon stockings.

The mascara of night

applies itself to us. We

blush. It’s a shame.

We really have let it come to this.

The mourning

dove weds our reality to

the morning—

a melodic glue. In the obscene light

we see the results

of our night’s cruel

experiments: bra straps clasped onto

thin air, hacked

Barbie limbs, matte-white ceramic

shards in the ditch, like pieces of destroyed moon.

James Champion (he/him/his) is from Whitehall, Michigan.

He has a bad habit of looking only at his shoes as he walks place to place,

but this makes arrival (and the sky) a constant surprise. You can find him

online at @jameslchampion on Instagram or Twitter.

Casey Charles

Luck at First Sight

We had a German shepherd collie mix

who curled up on the braided oval like a fox

in the foyer at the foot of the stairs.

Her name was Lucky because we were lucky to have her,

lucky to sit in the crook of our fig tree

and watch her chase Bob the milkman

in his dairy truck down Seabury,

our street lined with blue agapanthus.

I wanted to find out what luck was,

why Mom played the slots at Crystal Bay

came back like the Silver Dollar Lady in Virginia City.

Why I smoked Lucky Strikes like the mechanic at the plant,

why his veined arms and tank top

dove down to the deep end of my pooling want,

why why me cried out when I got the virus

from a man I thought I loved. Who the Fool

in the Tarot was. How luck was supposed to be a lady

and not a lad. My lad pointing to water beds in Echo Park,

the ones framed by hard wood. Why I was convinced

the lottery would never be mine to win,

as if some configuration, or algorithm, some convergence

or will of God, some windy house built by Chaucer

or wheel spun by buxom blonds could prefigure

unsold copies, lost elections, a mealy peach--

something as simple as warming the bench

for every scrimmage, a slur hurled from a locker,

a bottom drawer of form letters, a pair of crossed eyes.

Was it aptitude or attitude, fear or a few extra pounds

that led to star alignment and Scorpio, to fix blame

on some lonely raven, find behind my prophecy

some wizard’s die or lot cast long ago.

I tried to use evidence of lost balls, flat tires in the Mojave,

an archive of pink slips and low credit scores,

a history of unreleased bindings and broken skateboards,

bad grammar and failed chemistry, tried to turn the past to providence,

self-sabotage to fate’s middle finger.

Proclivity became propensity, abstraction distraction,

chance a kind of writing on a predictable wall. I knew it.

That cat’s color excused my speeding ticket, my guilty plea,

my chance to host two plagues. It’s not my fault,

this decline of democracy in America. I just live here.

I just need a scapegoat in the yard to eat dandelions,

another long nap. I try to be agnostic

but when the only room in Idaho is a river suite for 395 a night

when the dashboard will not crack beneath a fist,

when Joe won’t call me back after countless messages

and my friends trash my kitchen while I’m gone,

when—minor though these be—odious as comparisons are--

determinism again kicks in like a mugging in Manhattan

or a partner who has called my bluff and left for good,

I have to face the sky, cry why to some sadistic overlord,

some angry Puritan with a whip, who, omniscient

and on a mission to thwart the felicity of harmless homos,

has morphed my masochism into a kind of folie à deux

even though I flunked French at State freshman year.

Casey Charles writes from Missoula, Montana and Palm Springs, California--from the deep red north and hot blue south. He publishes in all genres: poetry, novels, essays, nonfiction, and most recently a memoir called Undetectable, forthcoming from Running Wild Press. Lawyer, teacher, activist, dog-walker, Casey Charles works to look into queer questions. www.caseycharles.com

Luck at First Sight

We had a German shepherd collie mix

who curled up on the braided oval like a fox

in the foyer at the foot of the stairs.

Her name was Lucky because we were lucky to have her,

lucky to sit in the crook of our fig tree

and watch her chase Bob the milkman

in his dairy truck down Seabury,

our street lined with blue agapanthus.

I wanted to find out what luck was,

why Mom played the slots at Crystal Bay

came back like the Silver Dollar Lady in Virginia City.

Why I smoked Lucky Strikes like the mechanic at the plant,

why his veined arms and tank top

dove down to the deep end of my pooling want,

why why me cried out when I got the virus

from a man I thought I loved. Who the Fool

in the Tarot was. How luck was supposed to be a lady

and not a lad. My lad pointing to water beds in Echo Park,

the ones framed by hard wood. Why I was convinced

the lottery would never be mine to win,

as if some configuration, or algorithm, some convergence

or will of God, some windy house built by Chaucer

or wheel spun by buxom blonds could prefigure

unsold copies, lost elections, a mealy peach--

something as simple as warming the bench

for every scrimmage, a slur hurled from a locker,

a bottom drawer of form letters, a pair of crossed eyes.

Was it aptitude or attitude, fear or a few extra pounds

that led to star alignment and Scorpio, to fix blame

on some lonely raven, find behind my prophecy

some wizard’s die or lot cast long ago.

I tried to use evidence of lost balls, flat tires in the Mojave,

an archive of pink slips and low credit scores,

a history of unreleased bindings and broken skateboards,

bad grammar and failed chemistry, tried to turn the past to providence,

self-sabotage to fate’s middle finger.

Proclivity became propensity, abstraction distraction,

chance a kind of writing on a predictable wall. I knew it.

That cat’s color excused my speeding ticket, my guilty plea,

my chance to host two plagues. It’s not my fault,

this decline of democracy in America. I just live here.

I just need a scapegoat in the yard to eat dandelions,

another long nap. I try to be agnostic

but when the only room in Idaho is a river suite for 395 a night

when the dashboard will not crack beneath a fist,

when Joe won’t call me back after countless messages

and my friends trash my kitchen while I’m gone,

when—minor though these be—odious as comparisons are--

determinism again kicks in like a mugging in Manhattan

or a partner who has called my bluff and left for good,

I have to face the sky, cry why to some sadistic overlord,

some angry Puritan with a whip, who, omniscient

and on a mission to thwart the felicity of harmless homos,

has morphed my masochism into a kind of folie à deux

even though I flunked French at State freshman year.

Casey Charles writes from Missoula, Montana and Palm Springs, California--from the deep red north and hot blue south. He publishes in all genres: poetry, novels, essays, nonfiction, and most recently a memoir called Undetectable, forthcoming from Running Wild Press. Lawyer, teacher, activist, dog-walker, Casey Charles works to look into queer questions. www.caseycharles.com

|

Acadia Currah Vancouver, British Columbia

Little League Butterflies and a daisy with all the petals meticulously picked off. A game of “Does she love me, does she love me not” whispered into the grass. And you ask it not to tell anyone. It doesn’t answer. But that’s okay. It’s grass. You water that spot on the lawn every day anyway, in case it ever feels unforgiving. And you’ll sit your heart down at the kitchen table, sigh and say “I’m not mad, I’m just disappointed” The first time you kissed a girl, you looked over your shoulder the whole way home, desire as heavy as the devil on your back. And when you got home, you scrubbed your lips raw, thinking someone might see the shadow of another girl's lips on yours. And know. You know how to be a girl, with keychain wolverine claws and lipstick coffee cups. You know how to cross your legs and put a pillow over your stomach on the couch. You know how to be touched like a girl, hard and heavy and mean. Her hands are gripping your collar, burying her shame-flushed face in your lips. And you wish you knew how to be a boy, easy confidence and pressing into hips, pushing back short hair and leaning against a wall. But you don’t. So you improvise. And when you were about thirteen, you went to your friend's baseball game after school. And tried, honestly, to keep your eyes trained on the dirt-knees players. But despite your efforts, you find yourself drawn to the fathers, clutching wife-purses, faces red-hot yelling at pee-wee boys circling the pitch. A groan of disappointment, yelling at the referee, shoving popcorn in mouth like a starved animal. And you’re shadowboxing in the East Side Mario’s bathroom. He is nice, all “Get whatever you want.” and “Tell me about your family”. But your heart, regrown like a deformed lizard tail, a starfish leg, cannot. He will touch your hand across the table and you want to saw it off with your butterknife and give it to him, say “Here, take it.” Just take it. And you have your hands on the sink, looking into your own mascara eyes in the mirror. Come on. Let him pay, put his hand on the small of your back and move it to your leg in the passenger seat. And you think, so much of love with him and him and him would be about allowance, let him touch you, let him look at you. You’ll let him push your hair behind your ear, and whisper you look beautiful. And you’ll nod, and you’ll want to want. Leave the bathroom. “Game face.” And later you’ll walk down your suburban street on a hot day to a church of which you do not know the denomination. And it doesn’t matter anyway. You’ll let the carpet-burn your knees and you’ll ask to love like a woman, silent and starving. And Father, he’ll sigh like you’ve struck out, put down his foam finger and prescribe you multivitamin hail mary’s. He will tell you to plant your desire in the backyard, bury it and trim its branches. Nothing grows. There’s a girl, reaching over you to grab her bag “Do you mind?” “Yeah, no problem.” And the second time you kiss a girl, she whispers “This is nothing” over and over again. This is nothing, this is nothing. And it isn’t. It doesn’t have to be, she can press her warm mouth to yours in the fluorescent light that feels like dark. And you can burn like the rosary beads that press into your chest, picture them scattering on the linoleum if you pull too hard. She’ll smack your hand away from hers like a child reaching for the cookie jar. You don’t try again. And she has a boyfriend. He has big enough hands to love her. You understand, your chewed-nail fingers are only for catching on nylons while a movie plays in class. Only to squeeze like a stress ball when she gets a bad test score. His are to hold her waist, spin her around under streetlights, to hold her face while he devours her, wholly. You aren’t hungry, not like he is. You cannot love loud like a boy, cannot even fathom how. The first lesbian movie you ever saw featured two women kissing behind a pillar, pressing desperately, quietly, into one another. Loving good and hidden like they should. When you were twelve they taught you about love being sacrifice, how Jesus sacrificed himself on the cross as an ultimate show of love for humanity. And you think about how you could love your husband, how you must love him if it’d pain you to be with him, to sacrifice your happiness for a man you haven’t met being the idyllic, sacrificial version of love. And there are fourteen stations of the cross, all of which are printed in high definition on the walls of your middle school. And every single one makes you think, why? Why didn’t he put it down, and run as far away from Golgotha as possible, and stop telling people he was the messiah? “Do you like anyone in our class?” “Oh-, Josh A, I guess” You understand, later. The first time a boy loves you, you don’t know until much later. He tells you “I was so crazy about you! Couldn’t you tell?” and recalls throwing his jacket over a puddle like the male lead in a vaguely sexist movie. “I was so obvious back then” And you meet a girl at a party complaining about downing her second drink, you volunteer,too quickly, to get her another one “Are you cold? I can make tea” She looks at you, like she’s seeing past something “I’m okay.” The third time you kiss a girl, your mouth tastes like lukewarm raspberry vodka, and she’s leaning into you. She’s smiling, pecking vanilla lip gloss onto your mouth. You hadn’t realized how dry your lips had been before. “This is nothing” “What did you just say?” And you’re fun at parties until you’re just a dyke. You can smear your lipstick and giggle while boys are watching and return to a boyfriend-lap perch without raising alarm. Without explanation. “You don’t-like me, right?” You put down your cross, big and heavy as a baseball-bat. “Of course not.” The last time you are in a confession booth ever, you are apologizing. And you hear your mothers voice in your head, when she’d find you eating all the advent calendar chocolate on the second of december, “Are you sorry you did it or sorry you got caught?” And you aren’t sure. You make a home in the term bisexual, finding comfort in it’s ability to tell a half truth about you. You wear attraction to men like a too-big sweater you get for a childhood birthday. “She’ll grow into it” You don’t. But it works, for a while. And he’s looking at you across the table “Aren’t you going to finish your breadsticks?” You nod, “Right, yeah.” But you don’t let him pay, and you go home early. And you could allow him to love you, open car doors and look up from under your eyelashes. And you thought, maybe, if you just stayed long enough, gave it enough time, you could train yourself to love him, and him, and him. Practice tricks in the backyard, put yourself on a leash. And there, tied to an oak tree, you begin to wonder how to love without training, without trepidation and meticulously maintained composure. The fourth time you kiss a girl, her mouth tastes like spit. Her hands, a little bigger than yours, clutch your hips like a lifeline. And there’s a livewire between you, connecting frayed t-shirts and ill-fitting jeans. And you think, to love her would be about wanting. You grab her shoulders like a steering wheel. “Thank you.” She laughs a little. “You’re welcome?” And you kiss her again. Again and again and again. And you love like a girl, low and hazy and sparking. You know, that this feeling indicates a failure to hold a man like this, like you want to brand him with your fingerprints And you feel, a little bit, like a child, being called “it” in a playground game of tag. “I wasn’t playing anyway.” You let the grass go dead, you’ve never had a green thumb. The voice is there again. “Are you sorry you did it, or are you sorry you got caught?” And you know, definitively. “Neither.” Acadia Currah (She/They) is an essayist and poet residing in Vancouver, British Columbia. Their work explores her relationship with gender, sexuality, and religion. She is a leather-jacket-latte-toting lesbian, her work seeks to reach those who most need to hear it. Their work has appeared in The Spotlong Review and Defunkt Magazine. |

|

Ace Englehart

Catching Moments in the Difficult World for Adrienne Rich May 2020, after arriving home from our first

overnight camping trip together: I think of the trail we hiked, crossing the creek, that steep climb down into a Tennessee waterfall basin we found at the top of the mountain. I think of how many photos we took trying to capture ourselves in the perfect kiss. December 1991, Adrienne Rich mentions in a poem

a brutal murder in the Appalachian Mountains: a lesbian couple camping alone on the trail, shot at by a man across the river as they made love. She did not want to know how he tracked them, but I did. I wanted to know if it was true, and why. May 1988, it happened. He had done it,

feeling taunted by their touching. They had met him earlier, in passing. He had tracked them. He watched them, pointed his gun at them and shot. I wanted to know the name of what evil had been there, what last words the two women had shared, if her lover’s hand was the last thing Rebecca felt or the damp leaves, patiently waiting for help; whether it was Claudia’s eyes or Appalachian stars that shone last before her own fading sight that night. I choked on the horror I read. September 2020, lost in graduate research one night

and isn’t it funny how words join together so effortlessly to knock the wind from your chest? Breathless, detached, like catching the moment before the fall: I crawled into bed at 2AM that night, new images in my mind—women the same ages as us, similar places, names and body shapes-- moments I never want to be caught in, damp leaves I don’t want to feel in my hands, eyes I don’t want to watch fade from life and as I put my arm around the love of my life, I promise her we’ll bring the gun next time. Ace Englehart is a 30-year-old Richmond, Va native currently in Yorktown where she teaches high school English and advises the school's GSA. In 2021, she completed her MFA in Creative Writing at the University of Tennessee, and received a Bachelors in English from VCU. Her poems appear in online journal such as Persephone's Daughters, The Timberline Review, and The Appalachian Review. Ace enjoys karaoke, photography, and spending time with her wife Holly, their princess pup Zulu, and black cats Phantom and Phoebe.

|

|

Nathaniel Farcas Florida

Loves me not

He loves him, he does,

and this is a frequent cause of the wars waged inside his own head.

At the very least he knows he doesn’t love him in the way he should, the way a

better man than him might--

this helps him settle his mind,

helps him forget at least

for awhile.

He’s been finished with love for a long time now;

he knows he can’t go back and the last thing he wants is to try.

The idea of it makes him feel something he won’t admit is fear.

But he loves him.

Only sometimes, and certainly not most of the time.

He doesn’t love the machine he barks orders at.

When he’s blinded by anger,

ripping at matted hair,

throwing that scarred and broken body down onto the rocks,

he sees nothing worth loving in those gaunt cheeks and empty eyes.

He doesn’t love him when he falls,

when he bleeds,

when he falters

or stutters

or trips up--

nor does he love him when he performs perfectly.

Whatever he feels towards that blind obedience isn’t love; whatever he

feels when he hits him or grabs him or takes what he wants from him and gets

no response isn’t love,

and he knows that.

But he loves him.

It’s in the late nights when they’re alone together, when he’s had too

much to drink and his head

is spinning and his tongue is loose and consequences

seem like a faraway dream,

when he spills his guts out into the world and there’s only one person to listen.

He sees something then.

Perhaps it’s the alcohol blurring his vision,

perhaps it’s wishful thinking--

just him longing for someone to hear him,

to understand how desperately his chest aches, to know the depths

of his suffering—or perhaps the eyes that meet his across the table are softer than

usual.

Sometimes he dares to believe that might be the case.

Things are always back to normal by morning anyway.

But he loves him.

In those rare moments he loves him, and though it’s a sick twisted hopeless love

it’s love nonetheless, no matter how much he hates that, no matter if it makes him

sick to his stomach.

Perhaps even rarer are the times he’ll catch a tender look,

a favor completed he hadn’t asked for—in those moments he feels the

rusted gears of his heart start to creak and turn and shriek like a wounded beast.

Once when he’d been sick, lying in a feverish haze, he could’ve sworn that when

someone had pulled the covers up over him as he lay shivering in bed and placed

their hand on his cheek, he’d felt cool metal against his skin.

His heart had screamed louder then and the gears spun faster than ever.

He knows, always, these moments will mean nothing by the next day.

But he loves him.

In some fucked up way,

which he thinks might be the most he’s capable of,

he loves him.

And sometimes,

when he sees himself side-by-side with him,

when he looks down at his own bloodied hands and knows they’ll never shake as

badly

as the

hands that

clean up afterwards,

when he meets those dark eyes and sees some deep gentle sorrow—

sometimes he can’t help but wonder which of them is more human,

him or his broken old machine.

Loves me not

He loves him, he does,

and this is a frequent cause of the wars waged inside his own head.

At the very least he knows he doesn’t love him in the way he should, the way a

better man than him might--

this helps him settle his mind,

helps him forget at least

for awhile.

He’s been finished with love for a long time now;

he knows he can’t go back and the last thing he wants is to try.

The idea of it makes him feel something he won’t admit is fear.

But he loves him.

Only sometimes, and certainly not most of the time.

He doesn’t love the machine he barks orders at.

When he’s blinded by anger,

ripping at matted hair,

throwing that scarred and broken body down onto the rocks,

he sees nothing worth loving in those gaunt cheeks and empty eyes.

He doesn’t love him when he falls,

when he bleeds,

when he falters

or stutters

or trips up--

nor does he love him when he performs perfectly.

Whatever he feels towards that blind obedience isn’t love; whatever he

feels when he hits him or grabs him or takes what he wants from him and gets

no response isn’t love,

and he knows that.

But he loves him.

It’s in the late nights when they’re alone together, when he’s had too

much to drink and his head

is spinning and his tongue is loose and consequences

seem like a faraway dream,

when he spills his guts out into the world and there’s only one person to listen.

He sees something then.

Perhaps it’s the alcohol blurring his vision,

perhaps it’s wishful thinking--

just him longing for someone to hear him,

to understand how desperately his chest aches, to know the depths

of his suffering—or perhaps the eyes that meet his across the table are softer than

usual.

Sometimes he dares to believe that might be the case.

Things are always back to normal by morning anyway.

But he loves him.

In those rare moments he loves him, and though it’s a sick twisted hopeless love

it’s love nonetheless, no matter how much he hates that, no matter if it makes him

sick to his stomach.

Perhaps even rarer are the times he’ll catch a tender look,

a favor completed he hadn’t asked for—in those moments he feels the

rusted gears of his heart start to creak and turn and shriek like a wounded beast.

Once when he’d been sick, lying in a feverish haze, he could’ve sworn that when

someone had pulled the covers up over him as he lay shivering in bed and placed

their hand on his cheek, he’d felt cool metal against his skin.

His heart had screamed louder then and the gears spun faster than ever.

He knows, always, these moments will mean nothing by the next day.

But he loves him.

In some fucked up way,

which he thinks might be the most he’s capable of,

he loves him.

And sometimes,

when he sees himself side-by-side with him,

when he looks down at his own bloodied hands and knows they’ll never shake as

badly

as the

hands that

clean up afterwards,

when he meets those dark eyes and sees some deep gentle sorrow—

sometimes he can’t help but wonder which of them is more human,

him or his broken old machine.

Stories You Wouldn’t Tell

1.

You and I never meet.

We are both gone

by next year.

2.

You and I meet this time.

We speak briefly. I toy with the idea

of digging around inside your ribcage

for something. Your brittle bones crack

when my fingernails touch them, and

we pass pleasantries from hand to hand

until they slip through our fingers.

3.

You and I fall in love this time.

You jump, or maybe I do.

I like this version least of all.

4.

You and I fall in love this time.

I stay and stay and stay while you rip me apart,

shoveling handfuls of me into the earth.

A bowl of pomegranate seeds glitters in the sun,

red and sticky and sweet. Your lips are

stained with it and when you smile they crack.

I don’t know how this one ends.

5.

You and I fall in love, every time.

Your skin still tastes like vanilla rather than copper

and your knuckles are still smooth. We find each other

and I kiss your eyelids and your lips aren’t scarred

and the sun rises every morning, red and ripe,

like you could bite into it.

6.

You and I, in another life,

in any other life, in every other life.

You and I. You and I. You and I.

7.

You and I fall in and out of love.

I meet a boy whose hands are like hot coals,

like whiskey in my chest. No one else is you.

I don’t want them to be.

8.

I don’t remember if your eyes shone like

beetle shells or coins, or if your breath was like fire.

I don’t remember how it felt to ache for you.

I don’t think there’s anything left for you and I.

9.

It was nice while it lasted, though,

wasn’t it?

Nathaniel Farcas is a 19-year-old award-winning short story author and has been writing poetry since the age of six.

He is a proud member of the LGBTQIA community and his work explores the joy and heartbreak that live within his community.

He currently resides in Florida.

1.

You and I never meet.

We are both gone

by next year.

2.

You and I meet this time.

We speak briefly. I toy with the idea

of digging around inside your ribcage

for something. Your brittle bones crack

when my fingernails touch them, and

we pass pleasantries from hand to hand

until they slip through our fingers.

3.

You and I fall in love this time.

You jump, or maybe I do.

I like this version least of all.

4.

You and I fall in love this time.

I stay and stay and stay while you rip me apart,

shoveling handfuls of me into the earth.

A bowl of pomegranate seeds glitters in the sun,

red and sticky and sweet. Your lips are

stained with it and when you smile they crack.

I don’t know how this one ends.

5.

You and I fall in love, every time.

Your skin still tastes like vanilla rather than copper

and your knuckles are still smooth. We find each other

and I kiss your eyelids and your lips aren’t scarred

and the sun rises every morning, red and ripe,

like you could bite into it.

6.

You and I, in another life,

in any other life, in every other life.

You and I. You and I. You and I.

7.

You and I fall in and out of love.

I meet a boy whose hands are like hot coals,

like whiskey in my chest. No one else is you.

I don’t want them to be.

8.

I don’t remember if your eyes shone like

beetle shells or coins, or if your breath was like fire.

I don’t remember how it felt to ache for you.

I don’t think there’s anything left for you and I.

9.

It was nice while it lasted, though,

wasn’t it?

Nathaniel Farcas is a 19-year-old award-winning short story author and has been writing poetry since the age of six.

He is a proud member of the LGBTQIA community and his work explores the joy and heartbreak that live within his community.

He currently resides in Florida.

|

Robin Gow

I Dream the Hospital of Transgender Doctors Has my doctor always been kind? She says she’s prescribing me whatever body I need. Then, at today’s visit she asks three times “Do you have any other questions or concerns?” My tongue becomes a bicycle avalanche. I want to ask in return, “Do you ever feel like this? Do cis people feel like this?” Small on the altars of our medicine? Always trying to nest in my body? I am concerned I am too old to be looking for new ways to change as if one might create me. I want to ask, “How can I learn to breathe silver?” and “Can you tell me why at night my blood turns indigo?” No. This would be too much to admit. When I say all my doctors have been cisgender, I mean they have all been too certain. I want a hospital where my doctor is as catastrophic as me—so queer they’re no longer doctors. They’ll wear pink dresses and tweed jackets. Mustaches and lipstick. They’ll use a poem as a stethoscope. There will be a hall of x-rays to make our bones lucid and an IV of nothing but light. We will be mended but never fixed. There will be no cures or antidotes. I want to say Tell me doctor, will we already be dead or just not yet here? Today, I tell her I want a thicker needle to draw my testosterone up from the vial but I don’t say “Why does this have to come in a vial?” Sometimes to be queer is to long for everything that is not yet possible. Who else is going to hold onto purple? Who else is going to learn to breathe silver? In The Hospital of Transgender Doctors we often forget we are transgender, not out of fear or shame but out transcendence—a glow without invented words. So transgender we surprise ourselves each moment-- a body without systems to name it. We perform surgery with notebook paper. Write prayers to our divine and insert them in each other’s throats like resting birds. No one is in critical condition but also everyone is. There is a gallery of precipices we gaze into and there is nothing to be prevented. No one is clean and no one is saved and everyone stands in a past and a future bedroom. My doctor reviews the appointment. Plans for STD tests and a flu shot. I lie to my doctor when she asks for a third time, if “Do you have any questions or concerns?” I say, “No, I don’t.” Robin Gow is an autistic transgender and queer poet from rural Pennsylvania. They are the author of several poetry collections, an essay collection, and the YA novel in verse, A Million Quiet Revolutions. |

Caroline Hayduk Scranton, PA

I never learned

about the planets because there was a boy popping my bra strap in science class & I was too busy

trying to make sure my shirt sleeves were long enough my JCpenney training bra tucked away &

/ the math teacher who compared equations to having a mistress & / the cleaning guy who said

big birthday coming up through windex streaks & / the guy who rolled a poker chip up my thigh

throbbing at me without permission or pulse & / it’s why i can’t cut my hair short & / if a man

stops looking at me do i disappear & / have i been gay enough &/ can i still have sleepovers with

the girls & / do they know how small my hands are & / remembering to ask how are you after

saying anything about yourself & / emily’s mom crying on my porch that she can’t have a gay

child & do you know where they go & / what if my best friend wants to kiss: will god watch too

& / who’s your friend &/ you’ll never be a real person because of your problems with men.

Caroline Hayduk is a queer poet and educator in Scranton, Pennsylvania. She received her MA and MFA in Creative Writing

and Poetry from Wilkes University. She has been published in Penn Review.

I never learned

about the planets because there was a boy popping my bra strap in science class & I was too busy

trying to make sure my shirt sleeves were long enough my JCpenney training bra tucked away &

/ the math teacher who compared equations to having a mistress & / the cleaning guy who said

big birthday coming up through windex streaks & / the guy who rolled a poker chip up my thigh

throbbing at me without permission or pulse & / it’s why i can’t cut my hair short & / if a man

stops looking at me do i disappear & / have i been gay enough &/ can i still have sleepovers with

the girls & / do they know how small my hands are & / remembering to ask how are you after

saying anything about yourself & / emily’s mom crying on my porch that she can’t have a gay

child & do you know where they go & / what if my best friend wants to kiss: will god watch too

& / who’s your friend &/ you’ll never be a real person because of your problems with men.

Caroline Hayduk is a queer poet and educator in Scranton, Pennsylvania. She received her MA and MFA in Creative Writing

and Poetry from Wilkes University. She has been published in Penn Review.

|

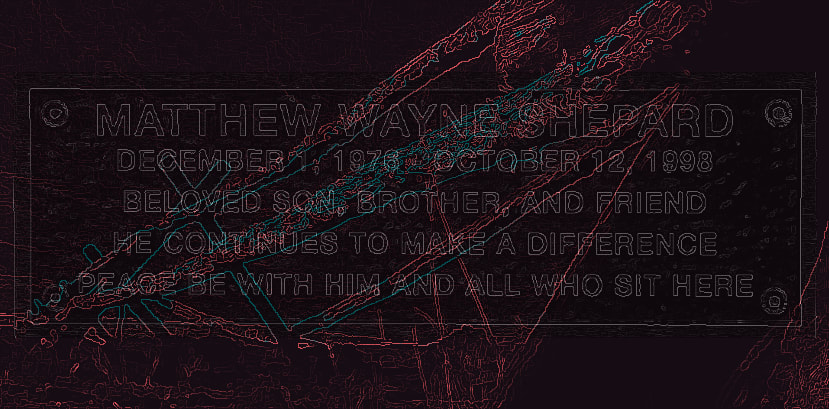

AE Hines Medellin, Colombia

Postcards from the Dead Ten years later, my killers interviewed from their cells will say: Matthew Shepard needed killing. Ten years after that, my people lay my ashes to rest in the shining capitol, under the stone ceiling of a vaulted cathedral, far from the fence in that naked winter field, from the icy prison of Wyoming. My killers thought I’d be forgotten when they offered me a ride, then bound my hands and placed that filthy bag over my head. But for ten years, for thirty, far longer than I was alive, our people remember my name. It blooms from their lips like a cold prairie rose. AE Hines is the author of Any Dumb Animal, his debut poetry collection released from Main Street Rag in 2021. His work has appeared in American Poetry Review, The Montreal Poetry Prize Anthology, Rhino, Ninth Letter, The Missouri Review, I-70 Review, Sycamore Review, and Tar River Poetry, among other places. Originally from North Carolina, he lived for many years in Portland, Oregon, and now resides part-time in Medellín, Colombia. www.aehines.net |

SG Huerta

Last Night You Said I Should Write More Queer Love Poems

But I just can’t stop watching Selling Sunset,

my TV right past my laptop, this blank Google

Doc that’s been staring me down. Davina (or

was it Heather?) just ordered a macadamia

milk latte, but I doubt it tops the H-E-B

coffee we take turns making each other

in the early mornings.

Lately, this is my only exposure

to straight culture, to (rich and mostly) white people,

to everything we aren’t and would never

want to be. The soundtrack is so consistently

bad– lyrics full of the unearned, unadulterated

confidence of #girlbosses. Would you believe

I didn’t know what a brokerage was until

two days ago? When I watch Amanza struggle

to remember the number of bathrooms

in the mansion she’s showing, I can’t help

but envision our dream home. Some must-

haves: at least one skylight, space for the cats,

shelves on shelves for the books you keep buying

me. Let’s take a shot of less-than-top-shelf

vodka every time an agent’s main motivation

is money, get too drunk to care about these strangers,

and lay in bed together, my head on your chest,

my heart completely yours.

Mortality, Gender, and Other Anxieties That Are Not Unique to Me

Bury me in my cherry red Doc Martens. Gender is a performance & my legs refuse to break.

Bury me with an iced oat milk latte. Bury me far away from my father. Gender is a performance

& I’m stuck backstage. Bury the cis girl I was before you bury the sort-of guy I am. Gender is

lineated poetry & I can’t stop writing prosaic stanzas. Bury me. Gender is. So on & so forth.

Bury my gender? Is that anything? Tell me it’s (I am) something.

SG Huerta is a Chicane writer from Dallas. They are the author of the chapbook

The Things We Bring with Us: Travel Poems (Headmistress Press, 2021), and their work has appeared in

Split Lip Magazine, Infrarrealista Review, Variant Lit, and elsewhere. They live in Texas with their partner and

two cats. Find them at sghuertawriting.com or on Twitter @sg_poetry.

Last Night You Said I Should Write More Queer Love Poems

But I just can’t stop watching Selling Sunset,

my TV right past my laptop, this blank Google

Doc that’s been staring me down. Davina (or

was it Heather?) just ordered a macadamia

milk latte, but I doubt it tops the H-E-B

coffee we take turns making each other

in the early mornings.

Lately, this is my only exposure

to straight culture, to (rich and mostly) white people,

to everything we aren’t and would never

want to be. The soundtrack is so consistently

bad– lyrics full of the unearned, unadulterated

confidence of #girlbosses. Would you believe

I didn’t know what a brokerage was until

two days ago? When I watch Amanza struggle

to remember the number of bathrooms

in the mansion she’s showing, I can’t help

but envision our dream home. Some must-

haves: at least one skylight, space for the cats,

shelves on shelves for the books you keep buying

me. Let’s take a shot of less-than-top-shelf

vodka every time an agent’s main motivation

is money, get too drunk to care about these strangers,

and lay in bed together, my head on your chest,

my heart completely yours.

Mortality, Gender, and Other Anxieties That Are Not Unique to Me

Bury me in my cherry red Doc Martens. Gender is a performance & my legs refuse to break.

Bury me with an iced oat milk latte. Bury me far away from my father. Gender is a performance

& I’m stuck backstage. Bury the cis girl I was before you bury the sort-of guy I am. Gender is

lineated poetry & I can’t stop writing prosaic stanzas. Bury me. Gender is. So on & so forth.

Bury my gender? Is that anything? Tell me it’s (I am) something.

SG Huerta is a Chicane writer from Dallas. They are the author of the chapbook

The Things We Bring with Us: Travel Poems (Headmistress Press, 2021), and their work has appeared in

Split Lip Magazine, Infrarrealista Review, Variant Lit, and elsewhere. They live in Texas with their partner and

two cats. Find them at sghuertawriting.com or on Twitter @sg_poetry.

Judy Ireland Lake Worth, FL

D.Q., She/Her

Judy Ireland is a poet, teacher, and amateur photographer.

Andie Jones Akron, OH

Armchair Confessional

I like to wrap myself in

pages of queer love

& sadness. Warmed

from the outside in, I settle

between the words.

But as I write

of the people I love, I am

stripped naked.

My skin a translucent

window to all the ways

I haven’t yet earned the right to lay

my queerness before the world

& call it

beautiful.

Andie Jones (they/them) is a transgender nonbinary and bi+

science teacher living in Akron, OH. They enjoy playing Stardew

Valley, listening to sad indie rock/pop, and eating far too much

popcorn in one sitting. They are as of yet previously unpublished

and currently owe all of their thanks to a special few friends and

partners for being their biggest cheerleaders and editors in all of

their writing endeavors. You can keep up with their art and bad

jokes on Twitter and Instagram at @andie_the_enby

Armchair Confessional

I like to wrap myself in

pages of queer love

& sadness. Warmed

from the outside in, I settle

between the words.

But as I write

of the people I love, I am

stripped naked.

My skin a translucent

window to all the ways

I haven’t yet earned the right to lay

my queerness before the world

& call it

beautiful.

Andie Jones (they/them) is a transgender nonbinary and bi+

science teacher living in Akron, OH. They enjoy playing Stardew

Valley, listening to sad indie rock/pop, and eating far too much

popcorn in one sitting. They are as of yet previously unpublished

and currently owe all of their thanks to a special few friends and

partners for being their biggest cheerleaders and editors in all of

their writing endeavors. You can keep up with their art and bad

jokes on Twitter and Instagram at @andie_the_enby

|

Paige Justice

The Closet A girl is playing hide-and-seek with her siblings. She hides in the deepest, darkest crevasse; deep enough so they cannot find her by just opening the door. Time isn’t real in the closet. At first, she is happy--look how well I’ve done! she thinks. As time goes on she sits in the darkness, waits in the darkness, becomes a part of the darkness; her siblings never find her. She soon starts to think that maybe they didn’t want to find her; didn’t want her to ruin their fun; didn’t want to be seen with her, or the other kids would make fun of them, too; they didn’t want her. The girl crawls towards the door, her hand outstretched; all she finds is cold, smooth sheetrock greeting her. She paws around, growing more frantic with each passing moment. She is sure the door is there, knows it is there; how else could she have gotten here? Maybe this is a dream. She presses her back against the wall, drawing her knees to her chest. She can’t see, but she presses the tips of her fingers against her thigh, one by one, until she comes to a stop at the tenth. Not a dream, she confirms. She can’t see, but she begins to hear a commotion. Three sets of feet thump against the solid oak floors, all coming to a sudden halt followed by the slam of a door. Who could be with them? she asks herself. It was just the three of them playing. Had her aunt stopped by, and brought her son? “Oh, I cannot wait to tell mom about this,” she hears her older brother say. “Looks like you’re going to be going back to therapy,” her sister taunts. Before she can question who it is, who they are making their latest victim of bullying, she hears a voice. Her chest tightens. “It wasn’t me!” the voice detests. She hears the guilt in the voice. She hears herself. This can’t be real, she whispers. Small beads of sweat begin to form on her upper lip. She hears the voice speak again. “Just don’t tell her,” the voice pleas, “I’ll do whatever you want.” She wants it to stop. She wants the darkness to end. She kicks the wall with the flat of her foot, putting all eighty-five pounds of force behind it. She screams for her life, to be found, for all of this to stop. The walls don’t budge. No one can hear her. She is alone. She is trapped in the closet. * Time isn’t real in the closet. She isn’t sure how long she’s been here, how long it has been like this. She thinks that maybe it has been years now. She hears everything. She hears the girls at school with their mocking words, their accusations of her being a predator. She hears the voice that sounds like hers. She hears the voice that doesn’t acknowledge her screams for freedom, her pleas to see the light of day. She hears the voice of the liar, who responds that those girls are “just bitches with nothing better to do” when her mother questions why she’s heard talk around town that her daughter is a predator looking to corrupt other girls with the “sickness” she has. The closet is smaller now. She takes up more space. She isn’t sure if so much time has passed that she is growing, or if the walls are closing in with every lie the voice tells. She thinks that it’s probably both. She makes a bet with herself about which will happen first: she will finally find a way out of this place—find the door, make her own damn door—or there will be too many lies, no way out, and she will be nothing more than a mixture of blood and brains left canvasing the walls of this goddamn closet. Her bet is on the latter. * The girl is now a woman. For the first time in a decade, she thinks, she begins to see light. There is nothing but blinding, illuminating whiteness. The time has come, she thinks. She has finally died. This is the light they had taught her about in church, the one that she was supposed to follow to take her to her eternal destination. She hears nothing but the screams and sobs of her mother, the sound of sheetrock shattering against her father’s fists. She is confused. She wonders why they aren’t happy to see her, to see their real daughter —not the imposter who has been living as her for the past ten years. She begs them to listen. She tells them about how she has been trapped in a closet for the past ten years, about how someone had locked her in there and took her place, about how she had wanted to tell them the truth even then but she herself didn’t have the words for it, that she didn’t understand it, that she still doesn’t. They tell her she is sick. They tell her she is crazy. They tell her they are going to get her help, so they can get their daughter back. Her eyes adjust. Everything looks just as she remembers it. She looks in the mirror. She doesn’t know the woman staring back at her. * The woman leaves before her parents can ship her off to be tortured, to be changed, to be confined in that closet forever. She struggles, at first. She has no money, no car, no place to sleep. She has no friends, no family, no one to call for help. She finds shelter in old sheds, alley ways, and occasionally under the stars in a hammock when the weather allows it. She has nothing, but she has never been happier—happy to be free, to not lie, to be seen for who she really is. She’s good at hiding it, her homelessness, just as she has always been good at hiding things. She keeps herself well-groomed, and has enough outfits, that people at work don’t even question the possibility of her unfortunate reality. Eventually, the woman makes friends. She doesn’t lie to them about who she is, or what she’s been through, but she doesn’t talk about the closet. Part of her is still afraid that maybe, somehow, she will be forced back to that place. The other part of her is afraid that maybe her parents were right, that she is sick, she is crazy. She meets a woman, and she learns what it means to fall in love and to be loved for who you truly are. At first, she is scared. She has never done this. She has been taught that it is wrong to do this, that people who did things such as this are sick. She learns that all of the things she was taught as a child are a lie. She knows, first-hand, that there is nothing more beautiful than a love like this, than the love that two women can share. The woman whispers soothing mantras and caresses her cheek every night when she inevitably kicks and screams herself awake, when the memories of the darkness, the confinement, consume her dreams. * The woman has a family of her own now and has made a beautiful life for herself. She has been with her wife for nine years. She hasn’t heard from her family in ten. She has a daughter and a son, twins. They have never met their grandma and grandpa, or aunt and uncle. She hopes that they never do. She will make sure they never do. She works to help children who are going through the same thing that she did. She runs a homeless shelter for LGBTQ+ youth and works as a counselor. She helps them process the trauma from all of the years that they were trapped in the closet, too. * The woman’s children ask her, beg her, to play hide-and-seek. She can’t say no. Inevitably, no matter how hard she tries to avoid it, it is her turn to hide. She scurries through the house, growing more frantic as each space she finds becomes smaller than that last, no place large enough to harbor her. She stands, staring. The closet is her only option. She hasn’t been in a closet since she was a girl, since she got trapped last time. Her therapist told her that she needed to do this, to expose herself to her fears, years ago. She never listened. The woman hears small footsteps approaching and takes a deep breath. Her shaking hand grasps the knob, and she finds herself in the deepest, darkest crevasse. At first, she remains calm. The ticking of her watch allows her to keep track of time. Ten minutes isn’t too long. The kids are young. She isn’t worried that they haven’t found her yet. Her kids love her. Her wife loves her. They want her. She knows they will not leave her here, alone. They will not allow her to be replaced by an imposter. Maybe they thought they weren’t allowed in here, the woman assures herself. Standing up, she steps forward and reaches towards the door. Her throat begins to burn, as her heart attempts to claw its way out of her body. Not again, the woman declares, I’m not getting stuck here again. * Time isn’t real in the closet. She isn’t sure how long she’s been here, how long it has been like this. She knows how to handle this now, though. She has spent enough time here, enough time fearing being brought back here, that she knows she can find her way out. She doesn’t give up hope. She doesn’t stop fighting to get out. She doesn’t go unheard. She knows what she has to do. Her fists slam into the walls. She can taste the blood in her throat, and her voice is indistinguishable. She doesn’t know how long she’s been yelling for help. Slowly, the door begins to creak open; a dark, slender figure towers over her. As her eyes adjust, she sees her mother reaching towards her. “Honey, come out of the closet,” her mother sighs, “you were just having another nightmare.” Paige Justice is a Professor and Academic & Student Success Director in Huntington, West Virginia. Her creative writing examines the duality and conflict that arises via the intersection of Queer and Appalachian identities. Her essay "The Appalachian Black Sheep" is forthcoming in the anthology Riding Fences: Essays on Being LGBTQ+ in Rural Areas. |

Ben Kline Cincinnati, OH

Brief History of Saying Gay

Kids have been saying gay since they encircled us

on the monkey bars, sniffing fear in our armpits, jeering

our toes on point and backpack diva graffiti, the hate

curling their grins, too fun to stop, too much to change

until the legislatures reach a disco quorum of dykes, faggots,

sissies, all our friends between revolutions, maybe some p-flags,

every bill a backbeat our syncopated hearts propel

to four on the floor choruses where we find it—freedom

from politics and gods, freedom in our hips and acrobatics

of the wrist, every playground a fall, ankles rolled before trying

again when an open hand says here, hold on, stay beautiful,

and the sun recedes, light pink as heartbreak going on

without us, our knees cracking over the bar, our hair admitting

gravity’s sway, fingers tickling the green blades.

Ben Kline (he/him) lives in Cincinnati, Ohio. Author of the chapbooks SAGITTARIUS A*

and DEAD UNCLES, Ben was the 2021 recipient of Patricia Goedicke Prize in Poetry and the winner

of the 2020 Christopher Hewitt Award for poetry. His work appears in South Carolina Review, Autofocus Lit,

bedfellows magazine, POETRY, Rejection Letters, Southeast Review, The Shore, fourteen poems and many

other publications. You can read more at https://benklineonline.wordpress.com/

Brief History of Saying Gay

Kids have been saying gay since they encircled us

on the monkey bars, sniffing fear in our armpits, jeering

our toes on point and backpack diva graffiti, the hate

curling their grins, too fun to stop, too much to change

until the legislatures reach a disco quorum of dykes, faggots,

sissies, all our friends between revolutions, maybe some p-flags,

every bill a backbeat our syncopated hearts propel

to four on the floor choruses where we find it—freedom

from politics and gods, freedom in our hips and acrobatics

of the wrist, every playground a fall, ankles rolled before trying

again when an open hand says here, hold on, stay beautiful,

and the sun recedes, light pink as heartbreak going on

without us, our knees cracking over the bar, our hair admitting

gravity’s sway, fingers tickling the green blades.

Ben Kline (he/him) lives in Cincinnati, Ohio. Author of the chapbooks SAGITTARIUS A*

and DEAD UNCLES, Ben was the 2021 recipient of Patricia Goedicke Prize in Poetry and the winner

of the 2020 Christopher Hewitt Award for poetry. His work appears in South Carolina Review, Autofocus Lit,

bedfellows magazine, POETRY, Rejection Letters, Southeast Review, The Shore, fourteen poems and many

other publications. You can read more at https://benklineonline.wordpress.com/

Koss

Gayke Manifesto

Gayke is a universal healing modality by which practitioners carry out the Source's will by

turning people gay, lesbian, bi or transgender through energy transmissions—including, and

especially, remotely. God (the Source) has a sensitivity training protocol by which humans are

expected to become less hateful, more compassionate and less judgmental. The primary

component to the sensitivity training is carried out by skillful and dedicated Gayke practitioners

who are now collectively focused on turning the Bible Belt gay by remote means.

Once the Bible Belt conversion is complete, on to Rome and beyond. Conversions have been

increasingly successful with the help of the media, including Fox News (the Bible Belt station),

Facebook and Google. Gayke practitioners have found that the low frequency vibrations of

negative media are conducive to clear channeling and transmission of divine Gayke energy, as

the wave lengths are incompatible. In other words, any publicity is good publicity.

Neither Google nor Facebook have decoded the divine algorithms of Gayke, nor will they.

Higher frequency Source energy is difficult, if not impossible to detect by web crawlers, Google

Analytics or other digital means. Divine Gayke energy has consistently bypassed all government

air and missile defense radar.

Gayke statisticians and tacticians have tracked and ensured success through their own highly-

sophisticated algorithms and an omni-database developed by God. Direct conversions have been

on the rise, with indirect conversions and large-quantity referrals climbing in record-breaking

numbers.

Gayke practitioners will continue to carry out the Source's divine sensitivity training plan quietly,

peacefully, and undetected as they receive new directives through the emerging SCUM

management team, which is finalizing its energy-based protocol through divine instructions from

the Source. There is no need to panic, as the conversion process is very painless with guaranteed

increase in loving feelings for all. You may not notice any change once converted until you wake

up in the morning with a same sex stranger (or two), or, perhaps, your best friend, after an

evening of drinking. You may also find yourself wandering into the wrong bathroom or buying

Pez dispensers at the checkout. This is normal. Love yourself and receive the abundant love

around you in the Source-Approved New Age of Universal Love for All.

Koss has work in or forthcoming in Diode Poetry, Five Points, Hobart, Gone Lawn, Bending Genres, Up the Staircase Quarterly, Chiron Review,

Spillway, San Pedro River Review, Spoon River Poetry Review, Bull, Westchester Review, Kissing Dynamite, Schuylkill Valley and many others.

They were in Best Small Fictions 2020 and won the 2021 Wergle Flomp Humor Poetry Award, plus received BOTN nominations in 2021 for fiction

(Bending Genres) and poetry (Kissing Dynamite). Twitter @Koss51209969. Website: http://koss-works.com

Gayke Manifesto

Gayke is a universal healing modality by which practitioners carry out the Source's will by

turning people gay, lesbian, bi or transgender through energy transmissions—including, and

especially, remotely. God (the Source) has a sensitivity training protocol by which humans are

expected to become less hateful, more compassionate and less judgmental. The primary

component to the sensitivity training is carried out by skillful and dedicated Gayke practitioners

who are now collectively focused on turning the Bible Belt gay by remote means.

Once the Bible Belt conversion is complete, on to Rome and beyond. Conversions have been

increasingly successful with the help of the media, including Fox News (the Bible Belt station),

Facebook and Google. Gayke practitioners have found that the low frequency vibrations of

negative media are conducive to clear channeling and transmission of divine Gayke energy, as

the wave lengths are incompatible. In other words, any publicity is good publicity.

Neither Google nor Facebook have decoded the divine algorithms of Gayke, nor will they.

Higher frequency Source energy is difficult, if not impossible to detect by web crawlers, Google

Analytics or other digital means. Divine Gayke energy has consistently bypassed all government

air and missile defense radar.

Gayke statisticians and tacticians have tracked and ensured success through their own highly-

sophisticated algorithms and an omni-database developed by God. Direct conversions have been

on the rise, with indirect conversions and large-quantity referrals climbing in record-breaking

numbers.

Gayke practitioners will continue to carry out the Source's divine sensitivity training plan quietly,

peacefully, and undetected as they receive new directives through the emerging SCUM

management team, which is finalizing its energy-based protocol through divine instructions from

the Source. There is no need to panic, as the conversion process is very painless with guaranteed

increase in loving feelings for all. You may not notice any change once converted until you wake

up in the morning with a same sex stranger (or two), or, perhaps, your best friend, after an

evening of drinking. You may also find yourself wandering into the wrong bathroom or buying

Pez dispensers at the checkout. This is normal. Love yourself and receive the abundant love

around you in the Source-Approved New Age of Universal Love for All.

Koss has work in or forthcoming in Diode Poetry, Five Points, Hobart, Gone Lawn, Bending Genres, Up the Staircase Quarterly, Chiron Review,

Spillway, San Pedro River Review, Spoon River Poetry Review, Bull, Westchester Review, Kissing Dynamite, Schuylkill Valley and many others.

They were in Best Small Fictions 2020 and won the 2021 Wergle Flomp Humor Poetry Award, plus received BOTN nominations in 2021 for fiction

(Bending Genres) and poetry (Kissing Dynamite). Twitter @Koss51209969. Website: http://koss-works.com

Danielle Lemay Central California

Christmas Card

A college student, I ate ravioli

in a booth at the Old Spaghetti Factory

in Boston, Massachusetts, 1995

with three friends: a husband, his wife,

and a soon-to-be-ex friend who says

Let’s line up all the gays

and shoot ‘em.

The husband, now a U.S. Congressman,

and his wife share their family Christmas photo

online in December 2021

with every member toting a gun,

and not the hunting kind,

unless they’re hunting people,

killing large groups at a time,

all in a line.

Danielle Lemay is a poet and a scientist who grew up in Florida

and now lives in central California. Her poetry has been nominated

for Best of the Net and has appeared in SWWIM Every Day, California

Quarterly, San Pedro River Review, and elsewhere. Read more at www.daniellelemay.com

Christmas Card

A college student, I ate ravioli

in a booth at the Old Spaghetti Factory

in Boston, Massachusetts, 1995

with three friends: a husband, his wife,

and a soon-to-be-ex friend who says

Let’s line up all the gays

and shoot ‘em.

The husband, now a U.S. Congressman,

and his wife share their family Christmas photo

online in December 2021

with every member toting a gun,

and not the hunting kind,

unless they’re hunting people,

killing large groups at a time,

all in a line.

Danielle Lemay is a poet and a scientist who grew up in Florida

and now lives in central California. Her poetry has been nominated

for Best of the Net and has appeared in SWWIM Every Day, California

Quarterly, San Pedro River Review, and elsewhere. Read more at www.daniellelemay.com

Jason Masino

I wanna talk

I wanna talk about confidence

& panic attacks in the grocery store

& induced seizures from my favorite childhood episodes of Jackie Chan Adventures

& stubbing my toe on a glass coffee table

I wanna talk about the danger

of throwing yourself into an Uber for 15 minutes just to get laid

& not sure if you’ll make it back in one piece but also not really caring

I wanna talk about the craving

of $3 hot dogs grilled on the sidewalk with too much mayo & not enough onions & of all

the mixed drinks, just like my heritage, bubbling into something deadly, waiting for more chemicals

- chemicals on chemicals

I wanna talk about proper grammar & how it’s inherently racist but I implore its use so I’m just

another pot calling the kettle black

I wanna talk about how I love to dry clean my favorite slacks & wear boots that click when I

walk down the halls so bitches know that I’m coming for their spot

I wanna talk about how it doesn’t make sense that doing it doggy style makes you a slut when we

collectively know that that title is reserved for missionary

I wanna talk about horror films & taxidermied animals on the bookshelf & how I’d fit in nicely

on top as a bookend

I wanna talk about us & we & them & how Zoloft costs too much but mixes nicely with

Prosecco & cheesecake

I wanna talk about big mouths & big brains with balls to match & how they can barely fit into a

skirt so we call it a kilt

I wanna talk about how you can’t shut me up but continually shut me out, shut me down, grind

me into fine powder and rub me into your gums

Jason Masino (he/they) is an artist and a Los Angeles native, he received his BA in Dramatic Art from the University of California,

Davis in 2010 and his MFA in Poetry at Regis University in Denver, Colorado in 2022. His work has been published in Cultural Weekly,

Inverted Syntax, Rigorous, Call + Response, Squircle Line Press, and others.

I wanna talk

I wanna talk about confidence

& panic attacks in the grocery store

& induced seizures from my favorite childhood episodes of Jackie Chan Adventures

& stubbing my toe on a glass coffee table

I wanna talk about the danger

of throwing yourself into an Uber for 15 minutes just to get laid

& not sure if you’ll make it back in one piece but also not really caring

I wanna talk about the craving

of $3 hot dogs grilled on the sidewalk with too much mayo & not enough onions & of all

the mixed drinks, just like my heritage, bubbling into something deadly, waiting for more chemicals

- chemicals on chemicals

I wanna talk about proper grammar & how it’s inherently racist but I implore its use so I’m just

another pot calling the kettle black

I wanna talk about how I love to dry clean my favorite slacks & wear boots that click when I

walk down the halls so bitches know that I’m coming for their spot

I wanna talk about how it doesn’t make sense that doing it doggy style makes you a slut when we

collectively know that that title is reserved for missionary

I wanna talk about horror films & taxidermied animals on the bookshelf & how I’d fit in nicely

on top as a bookend

I wanna talk about us & we & them & how Zoloft costs too much but mixes nicely with

Prosecco & cheesecake

I wanna talk about big mouths & big brains with balls to match & how they can barely fit into a

skirt so we call it a kilt

I wanna talk about how you can’t shut me up but continually shut me out, shut me down, grind

me into fine powder and rub me into your gums

Jason Masino (he/they) is an artist and a Los Angeles native, he received his BA in Dramatic Art from the University of California,

Davis in 2010 and his MFA in Poetry at Regis University in Denver, Colorado in 2022. His work has been published in Cultural Weekly,

Inverted Syntax, Rigorous, Call + Response, Squircle Line Press, and others.

Bryan Monte

The Bonfire

Magnus Hirschfeld (1865-1935); Brown University Library, 1985

I.

Will I ever hear your name unless I say it?

You, the great-grandfather of my history--

doctor, confessor, writer, orator.

Your name is missing from the university library.

White hair and a mustache, hand resting on your chin

face framed by wire glasses and a cravat,

I study your picture from a book

found by accident in a second-hand store

as if it were a mirror

or a map of directions.

The year your friend visited Wilde in jail

you founded the Institute for Sexual Science in Berlin

giving up your private practice for the problems of thousands

students in Charlottenburg, metal workers in Neuköln, prisoners in Tegel

free medical advice, lectures open to the public, marriage counseling.

For this they fined you again and again.

For 36 years you fought with charts, talks, films, books and exhibits,

a witness to the sexual diversity of humanity.

II.

The city’s libraries are to be cleansed of books of un-German spirit…

Students of the Gymnastik Academy are to start with the Institute of Sexual Science.

The Berliner Morgenpost, May 6, 1933

The rumble of lorries came early in the morning

rattling windows like a sudden storm, the pounding

spreading from the front door down the corridor

from room to room, students demanding keys

to offices, records, libraries they could ransack

pouring inkwells over files, throwing books, charts,

card catalogues to the bonfire below

a brass band playing drinking songs

burning pages and ashes floating

back up through the windows.

In a torchlight parade a few days later

they carried your bust on a pike down the street

to the Operplatz:

Freud, Einstein, Zola and Proust

Wilde, Carpenter, Gide and Marx

two truckloads, ten thousand of your irreplaceable volumes

fed to the flames, students and soldiers singing

at this, their destruction of understanding.

III.

I thumb through the university’s card catalogue once again,

this high-rise cemetery, this file of the dead and the living

numbed by your conspicuous absence

and the presence of those you opposed

still quoted in Canada’s and Great Britain’s parliaments

fifty years after your death

my magazines turned back

at both borders the bookstores warning:

Please do not list the name of your press

on your mailing envelopes as Customs

seizes all gay material as pornographic.

Blackened by the ashes of the world’s greatest crematoria

I sift through the layers of crumbling books

searching for the lost civilizations

of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Bryan R. Monte was shortlisted for the Hippocrates Open Poetry Prize

and the Gival Press Oscar Wilde Award in 2021. His poetry has appeared

recently in The Arlington Literary Journal, Irreantum, Italian Americana,

and Kaleidoscope Magazine (UDS), and is forthcoming in the anthology,

Without a Doubt, (New York Quarterly Books). His book, On the Level:

Poems on Living with Multiple Sclerosis, will be published by Circling Rivers

in November 2022.

The Bonfire

Magnus Hirschfeld (1865-1935); Brown University Library, 1985

I.

Will I ever hear your name unless I say it?

You, the great-grandfather of my history--

doctor, confessor, writer, orator.

Your name is missing from the university library.

White hair and a mustache, hand resting on your chin

face framed by wire glasses and a cravat,

I study your picture from a book

found by accident in a second-hand store

as if it were a mirror

or a map of directions.

The year your friend visited Wilde in jail

you founded the Institute for Sexual Science in Berlin

giving up your private practice for the problems of thousands

students in Charlottenburg, metal workers in Neuköln, prisoners in Tegel

free medical advice, lectures open to the public, marriage counseling.

For this they fined you again and again.

For 36 years you fought with charts, talks, films, books and exhibits,

a witness to the sexual diversity of humanity.

II.

The city’s libraries are to be cleansed of books of un-German spirit…

Students of the Gymnastik Academy are to start with the Institute of Sexual Science.

The Berliner Morgenpost, May 6, 1933

The rumble of lorries came early in the morning

rattling windows like a sudden storm, the pounding

spreading from the front door down the corridor

from room to room, students demanding keys

to offices, records, libraries they could ransack