SoFloPoJo Contents: Home * Essays * Interviews * Reviews * Special * Video * Visual Arts * Archives * Calendar * Masthead * SUBMIT * Tip Jar

Interview With A Poet- 3 Poets, 5 Questions, Each Month 2016-2019

- Dec 2019: Kathy Fagan, Victor B. Johnson, Sr.

- Nov 2019: Mary Galvin, Anannya Dasgupta, Yvonne Zipter

- Oct 2019: Crystal Boson, Glen Wilson

- Sep 2019: Amirah Al Wassif, Claus Ankersen, Judy Ireland

- Aug 2019: Marci Cancio-Bello, Paul Hostovsky, Flose Boursiquot

- Jul 2019: Fang Bu, Tony Barnstone, Gabriella Garofalo

- Jun 2019: Sanjeev Sethi, Melissa Studdard, Austin Davis

- May 2019: David Trinidad, Thomas Fucaloro, Chris Bluemer

- Apr 2019: Terese Svoboda, Angela Narciso Torres, Emma Trelles

- Mar 2019: Susan Deer Cloud, Bunkong Tuon, Robbi Nester

- Feb 2019: Charles Scheitler, Kristin Garth, Drew Pisarra

- Jan 2019: Jesse Millner, Elizabeth Jacobson, Ray Neubert

- Dec 2018: Yaddyra Peralta, David Estringel, Arminé Iknadossian

- Nov 2018: David Kirby, Jen Karetnick, Sean Sexton

- Oct 2018: Catherine Esposito Prescott, Eric Campbell, Mia Leonin

- Sep 2018: Marianne Szlyk, Patricia Carragon, Martina Reisz Newberry

- Aug 2018: Len Lawson, Nina Romano, Holly Lyn Walrath

- Jul 2018: Doug Ramspeck, Nicole Yurcaba, Indran Amirthanayagam

- Jun 2018: Joan Leotta, Caitlin Scarano, Joan Colby

- May 2018: Yuan Changming, Karen Paul Holmes, Gregory Byrd

- Apr 2018: Vicki Iorio, Alexis Bhagat, Lucia Leao

- Mar 2018: Geoffrey Philp, Sarah White, Richard Smyth

- Feb 2018: Grace Cavalieri, Allan Peterson, Jade Cuttie

- Jan 2018: L.B. Sedlacek, David B. Axelrod

- Dec 2017: Robert Cooperman, Ian Haight, Adam Levon Brown

- Nov 2017: Dorianne Laux, Catfish McDaris, Carolyne Wright

- Oct 2017: Caridad Moro-Gronlier, Joseph Fasano, Devon Balwit

- Sep 2017: Charles Rammelkamp, Susan Marie, Joshua Medsker

- Aug 2017: Julie Marie Wade, Akor Emmanuel Oche, Austin Alexis

- Jul 2017: Bryan R. Monte, Gregg Shapiro, Ace Boggess

- Jun 2017: Alan Catlin, Laurel S. Peterson, Ariel Francisco

- May 2017: Molly Peacock, Gregg Dotoli, Allison Stone

- Apr 2017: Cara Nusinov, Paul David Adkins, Elizabeth Upshur

- Mar 2017: Norman Minnick, J.S. Watts, J. Tarwood

- Feb 2017: Linda Nemec Foster, David Colodney, Suzette Dawes

- Jan 2017: John Arndt, Linda Avila, Bruce Sager

- Dec 2016: Denise Duhamel, Deborah Denicola, Maureen Seaton

- Nov 2016: Nicole Rollender, Jordi Alonso, Alexis Rhone Fancher

- Oct 2016: Peter Adam Salomon, Monalisa Maione, Nick Romeo

- Sep 2016: Trish Hopkinson, David Lawton, Laura Peña

- Aug 2016: Rick Lupert, Francine Witte, Jordi Alonso

- Jul 2016: Howard Camner, M.J. Iuppa, Jonathan Rose

- Jun 2016: Donna Hilbert, Lynne Viti, Rachel Galvin

- May 2016: Bruce Weber, Elisa Albo, C.S. Fuqua

- Apr 2016: Lyn Lifshin, Corey Mesler, Janet Bohac

- Mar 2016: Michael Hettich, Barbra Nightingale, Richard Ryal

- Feb 2016: Dianne Borsenik, Paul Saluk, Stacie M. Kiner

December 2019

Kathy Fagan

1 Who are you reading?

To be absolutely honest, I spend most of my time reading my students or former students right now—and that’s fine with me. They are all so different, one from another, and writing with much greater depth and understanding than I ever did when I was young. In addition, I read Poem-a-Day and Poetry Daily every day, and I have new poetry collections by Linda Bierds, Mary Ruefle, Rose M. Smith, Carmen Gimenez and Christopher Howell on my desk, along with the fiction and nonfiction I ride with in the car to keep me road-calm (Kiese Laymon, Elizabeth Strout, Toni Morrison) and in hard copy beside me in the mornings with whom I caffeinate (James Baldwin, Hilary Mantel, Kathryn Davis)

2 How often do you write/edit poetry?

I engage with poetry every day one way or the other and don’t fret anymore about which ways. I take notes for or revise my own work, and I make notes on my students’ poems. I also serve as series co-editor for the OSU Press/Wheeler Poetry Prize , so at the moment I have a few dozen semi-finalists’ manuscripts I’m looking through. I have found over the years that even when I’m not actively engaged in a poem of my own, I am engaged with poetry somehow, and on the rare occasions when I’m not, I’m experiencing something that will perhaps lead to a poem. I write words and phrases in my phone or notebook pretty much every day; poetry is no longer what I do, it’s who I am.

3 What do you think of literary magazine submission fees?

Hmm, I wish they didn’t exist, of course, but with the convenience of Submittable, I understand why they do. There are plenty of fine journals that do not charge submission fees, and I still tend to submit to them, when I get around to submitting poems, and encourage my students to do the same. It’s important to remember that editors and journals aren’t getting rich on submission fees; in fact, most of the editors I know personally don’t get paid for their work on behalf of other writers at all.

4 And MFA programs?

Well, I’m first-gen college, the product of one MFA program, and Director of another, so I have to say I am in favor. They’re not for everyone, but there are only a handful of places in smaller cities and towns where poets can find mentorship and community. An MFA program is one of those places, and if it also financially supports its writers for a few years, as ours does, so much the better. Writing complex, crafted and interesting poems is hard; finding a way in the poetry world may be even harder. I support any mechanism by which poets find their pursuit more tenable.

5 Do you send out snail-mail submissions?

I never send snail-mail submissions anymore—and I am a dinosaur so that’s saying a lot. I reserve snail-mail for personal notes and surprise packages, and still go to my local post office regularly because I sort of love it.

Kathy Fagan’s fifth book is Sycamore (Milkweed, 2017), a finalist for the 2018 Kingsley Tufts Award. She has received fellowships from the NEA, the Ingram Merrill and the Ohio Arts Council. Recent work has appeared in Poetry, Tin House and The Nation. Fagan directs the MFA Program at The Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio, where she also serves as series co-editor for the OSU Press/Wheeler Poetry Prize.

To be absolutely honest, I spend most of my time reading my students or former students right now—and that’s fine with me. They are all so different, one from another, and writing with much greater depth and understanding than I ever did when I was young. In addition, I read Poem-a-Day and Poetry Daily every day, and I have new poetry collections by Linda Bierds, Mary Ruefle, Rose M. Smith, Carmen Gimenez and Christopher Howell on my desk, along with the fiction and nonfiction I ride with in the car to keep me road-calm (Kiese Laymon, Elizabeth Strout, Toni Morrison) and in hard copy beside me in the mornings with whom I caffeinate (James Baldwin, Hilary Mantel, Kathryn Davis)

2 How often do you write/edit poetry?

I engage with poetry every day one way or the other and don’t fret anymore about which ways. I take notes for or revise my own work, and I make notes on my students’ poems. I also serve as series co-editor for the OSU Press/Wheeler Poetry Prize , so at the moment I have a few dozen semi-finalists’ manuscripts I’m looking through. I have found over the years that even when I’m not actively engaged in a poem of my own, I am engaged with poetry somehow, and on the rare occasions when I’m not, I’m experiencing something that will perhaps lead to a poem. I write words and phrases in my phone or notebook pretty much every day; poetry is no longer what I do, it’s who I am.

3 What do you think of literary magazine submission fees?

Hmm, I wish they didn’t exist, of course, but with the convenience of Submittable, I understand why they do. There are plenty of fine journals that do not charge submission fees, and I still tend to submit to them, when I get around to submitting poems, and encourage my students to do the same. It’s important to remember that editors and journals aren’t getting rich on submission fees; in fact, most of the editors I know personally don’t get paid for their work on behalf of other writers at all.

4 And MFA programs?

Well, I’m first-gen college, the product of one MFA program, and Director of another, so I have to say I am in favor. They’re not for everyone, but there are only a handful of places in smaller cities and towns where poets can find mentorship and community. An MFA program is one of those places, and if it also financially supports its writers for a few years, as ours does, so much the better. Writing complex, crafted and interesting poems is hard; finding a way in the poetry world may be even harder. I support any mechanism by which poets find their pursuit more tenable.

5 Do you send out snail-mail submissions?

I never send snail-mail submissions anymore—and I am a dinosaur so that’s saying a lot. I reserve snail-mail for personal notes and surprise packages, and still go to my local post office regularly because I sort of love it.

Kathy Fagan’s fifth book is Sycamore (Milkweed, 2017), a finalist for the 2018 Kingsley Tufts Award. She has received fellowships from the NEA, the Ingram Merrill and the Ohio Arts Council. Recent work has appeared in Poetry, Tin House and The Nation. Fagan directs the MFA Program at The Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio, where she also serves as series co-editor for the OSU Press/Wheeler Poetry Prize.

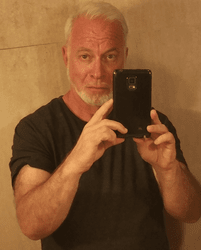

Victor B. Johnson Sr.

1 Who are you reading?

Paul Laurence Dunbar is an African American author and poet born in 1872 in Dayton, Ohio. His reputation grew upon how his verse and short stories where written in black dialect. He was the first black writer in the U.S. who attempted to live off the earnings of his writings and became the first to get national prominence. He started writing when he was only 6 years old, and was reading them out loud by 9. His first two poems, "Our Martyred Solider's" and "One the River", were published when he was 16 years old. Two years later he was writing for The Tattler. I enjoy his poems because some are short and some long with different styles of rhyming and non rhyming verse.

2 How often do you write/edit poetry?

I try to write everyday. Some days I write just a few lines then put it away and come back later to finish it. I make my own schedule since I am retired . I traveI, I take pictures, shoot videos and listen to music daily for inspiration.

3 What do you think of literary magazine submission fees?

When I first tried to get my poems published, I sent them in regularly. When I didn't hear back from them or they would say they couldn't use my poems, I started researching what other writers were saying and doing. They told me its a business and most of the time my poetry probably never was read. It's a business that gives a beginner hope of becoming a published writer without telling them how to improve their writing skills. It pays their bills and only a handful of writers get the break they are looking for.

4 And MFA programs?

They are great for someone who can afford the cost and wants to get into theatre, creative writing, visual arts or graphic design. It can open many doors on the professional level. MFA programs are not for everyone, myself included.

5 Do you send out snail-mail submissions?

No not anymore, since email has become so popular I prefer to get my submissions out as soon as possible.

Originally from Benton Harbor, Michigan and a Graduate from John Wesley College with a B.A. in Social Science, ITT-Tech AA in Networking Admin, Computer Tech Certificate from JTI, and certification in Mobile App developer from Google. Birdman31355 has been writing poetry for the past 30 years. He has nine published poetry books and four published poetry chapbooks and several poetry videos on DVD’s. Has been published in Forward Times Newspaper, Silver Birch Press, Storm Magazine, Harbinger Asylum, Indiana Review News Letter, The Permain Basin Poetry Society, Expressions Anthology, Dandelion in a Vase of Roses, Waco Word Fest Anthology, Button Poetry and No Mad's Choir Poetry Journey along with several Newsletters.

Birdman31355 has several Editor’s Choice Awards and one International award for his poetry. In addition, he has done editing for SOL Magazine, and readings at Open Mics includes Jump Cut Café in Thousand Oaks, Calif, Soapbox Sessions in Encino, CA., Waco Word Festm Waco,TX. ,Full English Coffee, Expressions, Kick Butt Coffee and Booze, Stomping Grounds, Buzz Mill, New World Deli, Malvern Books, Rad Radam, Strange Brew, Hot Mama’s, Texas Nafas, AIPF Festival, Awesmic City Expo in Austin, TX, Taft Street Coffee, Heights Book Store, Starving Artist Gallery, Jet Lounge, Costas Elixir Lounge, Houston, TX, Friendwoods public Library Friendswood, TX. Coffee Oasis, Murder by Chocolate, Nocturne Coffee Seabrook, TX. Maude Coffee Galveston, TX. October Fest, Barnes Nobile in Webster, TX. Chicago open mic Podcast and Cincinnati Orphanage in Cincinnati, Ohio.

He has appeared on blogtalk radio Maverick-Media, Dark and Delicious, Sister-Sister, The Shirley Ann Show, The Authors Corner Blog Talk Radio, Twin cities network radio programs, The Authors Lounge and CrowdPublish.TV. He was presented a plaque for the poem “She”, a gold medallion and a pendant. He is in a documentary (Poetry is Dead) by Vagabonds press. His Video "Forgotten Time" won first place in The Light Poetic Ministry Poety Video Contest and he has hosted the Spoken Word Contest at the National Black Book Festival in Houston,TX. Many of his poems and videos can be found on Instagram/author_poet_birdman31355

Youtube.com/AuthorPoetBirdman31355

Twitter.com/Birdman31355

Facebook.com/victorjohnson

"Author/Poet Birdman31355"

Paul Laurence Dunbar is an African American author and poet born in 1872 in Dayton, Ohio. His reputation grew upon how his verse and short stories where written in black dialect. He was the first black writer in the U.S. who attempted to live off the earnings of his writings and became the first to get national prominence. He started writing when he was only 6 years old, and was reading them out loud by 9. His first two poems, "Our Martyred Solider's" and "One the River", were published when he was 16 years old. Two years later he was writing for The Tattler. I enjoy his poems because some are short and some long with different styles of rhyming and non rhyming verse.

2 How often do you write/edit poetry?

I try to write everyday. Some days I write just a few lines then put it away and come back later to finish it. I make my own schedule since I am retired . I traveI, I take pictures, shoot videos and listen to music daily for inspiration.

3 What do you think of literary magazine submission fees?

When I first tried to get my poems published, I sent them in regularly. When I didn't hear back from them or they would say they couldn't use my poems, I started researching what other writers were saying and doing. They told me its a business and most of the time my poetry probably never was read. It's a business that gives a beginner hope of becoming a published writer without telling them how to improve their writing skills. It pays their bills and only a handful of writers get the break they are looking for.

4 And MFA programs?

They are great for someone who can afford the cost and wants to get into theatre, creative writing, visual arts or graphic design. It can open many doors on the professional level. MFA programs are not for everyone, myself included.

5 Do you send out snail-mail submissions?

No not anymore, since email has become so popular I prefer to get my submissions out as soon as possible.

Originally from Benton Harbor, Michigan and a Graduate from John Wesley College with a B.A. in Social Science, ITT-Tech AA in Networking Admin, Computer Tech Certificate from JTI, and certification in Mobile App developer from Google. Birdman31355 has been writing poetry for the past 30 years. He has nine published poetry books and four published poetry chapbooks and several poetry videos on DVD’s. Has been published in Forward Times Newspaper, Silver Birch Press, Storm Magazine, Harbinger Asylum, Indiana Review News Letter, The Permain Basin Poetry Society, Expressions Anthology, Dandelion in a Vase of Roses, Waco Word Fest Anthology, Button Poetry and No Mad's Choir Poetry Journey along with several Newsletters.

Birdman31355 has several Editor’s Choice Awards and one International award for his poetry. In addition, he has done editing for SOL Magazine, and readings at Open Mics includes Jump Cut Café in Thousand Oaks, Calif, Soapbox Sessions in Encino, CA., Waco Word Festm Waco,TX. ,Full English Coffee, Expressions, Kick Butt Coffee and Booze, Stomping Grounds, Buzz Mill, New World Deli, Malvern Books, Rad Radam, Strange Brew, Hot Mama’s, Texas Nafas, AIPF Festival, Awesmic City Expo in Austin, TX, Taft Street Coffee, Heights Book Store, Starving Artist Gallery, Jet Lounge, Costas Elixir Lounge, Houston, TX, Friendwoods public Library Friendswood, TX. Coffee Oasis, Murder by Chocolate, Nocturne Coffee Seabrook, TX. Maude Coffee Galveston, TX. October Fest, Barnes Nobile in Webster, TX. Chicago open mic Podcast and Cincinnati Orphanage in Cincinnati, Ohio.

He has appeared on blogtalk radio Maverick-Media, Dark and Delicious, Sister-Sister, The Shirley Ann Show, The Authors Corner Blog Talk Radio, Twin cities network radio programs, The Authors Lounge and CrowdPublish.TV. He was presented a plaque for the poem “She”, a gold medallion and a pendant. He is in a documentary (Poetry is Dead) by Vagabonds press. His Video "Forgotten Time" won first place in The Light Poetic Ministry Poety Video Contest and he has hosted the Spoken Word Contest at the National Black Book Festival in Houston,TX. Many of his poems and videos can be found on Instagram/author_poet_birdman31355

Youtube.com/AuthorPoetBirdman31355

Twitter.com/Birdman31355

Facebook.com/victorjohnson

"Author/Poet Birdman31355"

November 2019

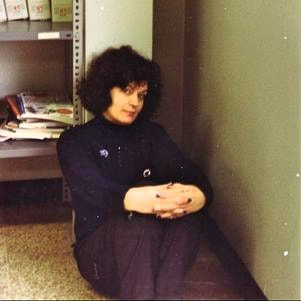

Anannya Dasgupta

1 Is there a poetic device/technique you seem to use more than any other?

I am partial to using rhyme. Rhyming poetry comes with the challenge of tending to sound trite or too contrived. Contemporary poets use it for its comic and satiric potential. But, having spent a lot of time reading renaissance poetry in English and having a fondness for lyric poetry, in English but also in Hindi, Urdu and Bengali, I am also not alone in thinking that good rhyming poetry lends itself to being inhabited, embodied and remembered in the bones. Rhyme, of course, does not work without rhythm which makes one pay careful attention to metre or line lengths that set up the reader / listener’s expectation of rhyme. One way for me to teach myself to use rhyme has been to write a lot of formal poetry that requires rhyme; my favorite forms being the sonnet, villanelle and the ghazal. Practicing writing in each of these forms has taught me different things about how to make rhyme, rhythm and repetition work. For instance, the ghazal, presents a particular challenge of a mono-rhyme in every second line of a couplet that is followed by word that is repeated. For instance, here are two couplets from my ghazal “Today”

Dust off the carpet, set out the

china, spruce up the nest today.

The wine in that bottle has long

since turned, empty the rest today.

Writing ghazals trained me out of the instinct for end rhymes only that writing the quatrains and couplets required of sonnets trained me into doing. It has impacted the way that I write some of my free verse now. I often use internal or end rhyme to end non-rhyming free verse. In that I am inspired by the couplet of the Shakespearean sonnet where the rhyme brings home a surprising but also conclusive end. It is often the volta of the couplet that will help make sense of the rest of the sonnet. I have been using this idea in some of my free verse. Here is one by way of illustration:

Venus Rising from the Sea

The first time I found a

scallop shell on the beach

I thought, but of course,

Venus, goddess of love,

born of the ocean,

rode this to the shore.

So sensuous to behold,

fanning out in shades of

fading rose, this would be

the abandoned carriage

of the goddess of love who

made a loveless marriage.

I think using rhyme reminds me of the artifice of poetry at the same time that it allows me to access something primal and deeply organic to the way we listen and remember.

2 Could you recommend a good essay about the craft of writing poetry?

The essay I have in mind is not about the craft of writing poetry per se but in effect it is exactly that. In his book The Art of Description , Mark Doty has a wonderful essay called “Tremendous Fish” in which the poet Doty close reads Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “The Fish” not as a literary critic as much as one poet reading another for mastery in craft. Doty’s objective is to get to the heart of the work of description, and the way that he reads Bishop’s poem is a masterclass in understanding the craft of narrative and lyric poetry. For instance, Doty establishes the structural scaffolding of the poem to show how Bishop’s poem shuttles her reader from “outward detail to inward association” as a prelude to lyric time. Here is a taste of the insights the essay holds on crafting the lyric: “Perhaps the dream of lyric poetry is not just to represent states of mind but to actually provoke them in the reader. Bishop’s poems restore us to a sense of energized, liberating uncertainty.”

3 Is there a person whose life you’d like to capture in a poem?

Not of an individual as of now, but if I could write about a cast of characters drawn from my familiar and distant surroundings, part mythic, part real as after Derek Walcott’s Omeros that would be something incredibly challenging and fun.

4 Should your readers “Google it” or do you need to clarify it in a note or epigraph?

I tend towards the note because that gives me a way to make sure that the relevant information is put right there on the page, and also in its way of writing the note is still a part of the moment of the poem. Readers will google what they must but that can also be distracting in going away from the words on the page. And if there is anything to be learned from Doty’s essay I mentioned earlier, it is also that we have to stay deliberately and elaborately with the words on the page in the writing of the poems and most certainly in reading them.

5 Tell us about your latest poem.

Poetry is my way to make sense of my surroundings and to cope. My latest poems are a series of short poems doing exactly that. I moved, not so long ago, for a job to a part of the country I have not lived in before. A geographically and culturally different landscape contours the shapes of things we know a little differently than before. And it can do that to something as familiar as rain

Rain in Sricity

Here rain does not fall

it descends in droves

of cattle, done kicking

up the dust of dusk,

now returning home to

parched new born calves

Anannya Dasgupta poems have appeared, among other places, in The South Florida Poetry Journal, Wasafiri, Pierene’s Fountain, The Literateur, All Roads Will Lead You Home, Madras Courier and The Ghazal Page. Her book of poems Between Sure Places came out in 2015. She is in the process of completing her next poetry manuscript The Weight of Air. She has lived in New Delhi and New Jersey where she completed her doctorate in English literature. She now lives in Chennai and works at Krea University as director of the Centre for Writing and Pedagogy and faculty in the division of Literature and the Arts.

I am partial to using rhyme. Rhyming poetry comes with the challenge of tending to sound trite or too contrived. Contemporary poets use it for its comic and satiric potential. But, having spent a lot of time reading renaissance poetry in English and having a fondness for lyric poetry, in English but also in Hindi, Urdu and Bengali, I am also not alone in thinking that good rhyming poetry lends itself to being inhabited, embodied and remembered in the bones. Rhyme, of course, does not work without rhythm which makes one pay careful attention to metre or line lengths that set up the reader / listener’s expectation of rhyme. One way for me to teach myself to use rhyme has been to write a lot of formal poetry that requires rhyme; my favorite forms being the sonnet, villanelle and the ghazal. Practicing writing in each of these forms has taught me different things about how to make rhyme, rhythm and repetition work. For instance, the ghazal, presents a particular challenge of a mono-rhyme in every second line of a couplet that is followed by word that is repeated. For instance, here are two couplets from my ghazal “Today”

Dust off the carpet, set out the

china, spruce up the nest today.

The wine in that bottle has long

since turned, empty the rest today.

Writing ghazals trained me out of the instinct for end rhymes only that writing the quatrains and couplets required of sonnets trained me into doing. It has impacted the way that I write some of my free verse now. I often use internal or end rhyme to end non-rhyming free verse. In that I am inspired by the couplet of the Shakespearean sonnet where the rhyme brings home a surprising but also conclusive end. It is often the volta of the couplet that will help make sense of the rest of the sonnet. I have been using this idea in some of my free verse. Here is one by way of illustration:

Venus Rising from the Sea

The first time I found a

scallop shell on the beach

I thought, but of course,

Venus, goddess of love,

born of the ocean,

rode this to the shore.

So sensuous to behold,

fanning out in shades of

fading rose, this would be

the abandoned carriage

of the goddess of love who

made a loveless marriage.

I think using rhyme reminds me of the artifice of poetry at the same time that it allows me to access something primal and deeply organic to the way we listen and remember.

2 Could you recommend a good essay about the craft of writing poetry?

The essay I have in mind is not about the craft of writing poetry per se but in effect it is exactly that. In his book The Art of Description , Mark Doty has a wonderful essay called “Tremendous Fish” in which the poet Doty close reads Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “The Fish” not as a literary critic as much as one poet reading another for mastery in craft. Doty’s objective is to get to the heart of the work of description, and the way that he reads Bishop’s poem is a masterclass in understanding the craft of narrative and lyric poetry. For instance, Doty establishes the structural scaffolding of the poem to show how Bishop’s poem shuttles her reader from “outward detail to inward association” as a prelude to lyric time. Here is a taste of the insights the essay holds on crafting the lyric: “Perhaps the dream of lyric poetry is not just to represent states of mind but to actually provoke them in the reader. Bishop’s poems restore us to a sense of energized, liberating uncertainty.”

3 Is there a person whose life you’d like to capture in a poem?

Not of an individual as of now, but if I could write about a cast of characters drawn from my familiar and distant surroundings, part mythic, part real as after Derek Walcott’s Omeros that would be something incredibly challenging and fun.

4 Should your readers “Google it” or do you need to clarify it in a note or epigraph?

I tend towards the note because that gives me a way to make sure that the relevant information is put right there on the page, and also in its way of writing the note is still a part of the moment of the poem. Readers will google what they must but that can also be distracting in going away from the words on the page. And if there is anything to be learned from Doty’s essay I mentioned earlier, it is also that we have to stay deliberately and elaborately with the words on the page in the writing of the poems and most certainly in reading them.

5 Tell us about your latest poem.

Poetry is my way to make sense of my surroundings and to cope. My latest poems are a series of short poems doing exactly that. I moved, not so long ago, for a job to a part of the country I have not lived in before. A geographically and culturally different landscape contours the shapes of things we know a little differently than before. And it can do that to something as familiar as rain

Rain in Sricity

Here rain does not fall

it descends in droves

of cattle, done kicking

up the dust of dusk,

now returning home to

parched new born calves

Anannya Dasgupta poems have appeared, among other places, in The South Florida Poetry Journal, Wasafiri, Pierene’s Fountain, The Literateur, All Roads Will Lead You Home, Madras Courier and The Ghazal Page. Her book of poems Between Sure Places came out in 2015. She is in the process of completing her next poetry manuscript The Weight of Air. She has lived in New Delhi and New Jersey where she completed her doctorate in English literature. She now lives in Chennai and works at Krea University as director of the Centre for Writing and Pedagogy and faculty in the division of Literature and the Arts.

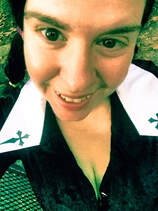

Yvonne Zipter

1 Is there a poetic device/technique you seem to use more than any other?

My favorite thing to do, in poems, is to write about what we often think of as commonplace and, through close observation, make accessible the extraordinary within them: to find the magic in everyday things. It’s easy to take the things, people, and animals around us for granted in a world where our attention is so often directed elsewhere. But I find that when I slow down and really pay attention to what’s around me, I am in awe of the complexities of nature or a bird or common moments or the people in my life. I take it as my job, as a poet, to try to put this awe into words for others who may not have taken notice of these things but realize, once I do find the right words, that this is just how they feel, too. In this way, I like to help others regain their own sense of wonder for the world. That sense of wonder is part of what keeps me young, I think. I am endlessly curious about the world around me.

2 Could you recommend a good essay about the craft of writing poetry?

To be honest, I’m not someone who often reads essays on craft—I tend, instead, to go directly to specific poems to try to figure out how the poet has created certain effects and/or handled a difficult subject. In essence, I guess I tend to learn by example. However, there is a Mary Oliver essay, titled “Sound,” that I found delightful and thought provoking. In it, she delineates the different families of sounds—including mutes, liquids, and aspirates—and the effect that these sounds have: “Now we see that words have not only a definition and possibly connotation, but also the felt quality of their own kind of sound” (A Poetry Handbook, p. 22). This is one of those things I think I’ve done for years—considering “the music” of a word—without the in-depth understanding of exactly what I was doing. I don’t think the essay changes how I write poems but it does, perhaps, give me a deeper understanding of what’s at work when I spend hours looking for precisely the right word in some line of a poem.

3 Is there a person whose life you’d like to capture in a poem?

What a timely question for me! I have actually been trying to write a poem about my mother’s 88-year-old cousin, whose life was incredibly difficult, in some ways, because of the cruel people around her. She could easily be bitter and mean-spirited, but when she recounts these stories, there is no hint of her feeling she’s been treated unfairly. She is matter of fact about the events and cruelties of her life, but chooses mostly to focus on the joys, from her little dog to her memories of family vacations in the woods of rural Wisconsin back in the 1940s. When I visited with her recently, she was barefoot and chattered on happily while making me the lunch she had insisted on preparing. The problem, in terms of writing a poem about her, is that I want to use every detail I know. Since I’m not planning on writing an epic poem, that clearly won’t do!

4 Should your readers “Google it” or do you need to clarify it in a note or epigraph?

I have employed notes following several poems, but those have been to indicate small passages quoted from other sources. In the main, I don’t think I tend to make too many obscure cultural references. That said, though, I guess I do expect readers to look up what they don’t know. I am sometimes surprised, however, that what I think is common knowledge might be new information to a reader. I happened on a short commentary about a recently published poem of mine in which the writer said: “And even Chet Baker we may only know through faint rumor. An old jazz singer? Blues?” It never occurred to me that anyone might not know who Chet Baker was.

5 Tell us about your latest poem.

I had read, not long ago, that scientists just discovered that giraffes hum at night. I also learned that some bats are known as whispering bats because of the low-intensity of their calls. I found both of these tidbits of information fascinating. Then, in August, my physician told me I had a heart murmur. Shortly thereafter, the lines “Giraffes hum. Bats whisper. / My heart murmurs” popped into my head. I walked around for several weeks with those two lines rattling in my brain until I finally sat down one day and wrote a little riff on my heart murmuring and what that might mean. The poem closes with musing about an echocardiogram. It is titled “Resound” in the sense of “to become filled with sound,” but also as in “about sound” (re: sound).

Yvonne Zipter is the author of the full-length collection The Patience of Metal (a Lambda Literary Award Finalist) and the chapbook Like Some Bookie God. Her poems have appeared in numerous periodicals over the years, including Poetry, Southern Humanities Review, Calyx, Crab Orchard Review, Metronome of Aptekarsky Ostrov (Russia), Bellingham Review, and Spoon River Poetry Review, as well as in several anthologies. Her poem “Osteosarcoma: A Love Poem,” originally published in Poetry, was reprinted in Writing and Understanding Poetry for Teachers and Students: A Heart’s Craft, edited by Suzanne Keyworth and Cassandra Robison. She is also the author of two nonfiction books: Diamonds Are a Dyke’s Best Friend and Ransacking the Closet. She is one of the founders of Hot Wire: A Journal of Women’s Music and Culture and a 1995 inductee into the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame. She received a fellowship to the Summer Literary Seminar in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 2004, an Illinois Arts Council Literary Award in 2001, and the Sprague/Todes Literary Award in 1997. Her published poems are currently being sold in two poetry-vending machines in Chicago, the proceeds from which are donated to a nonprofit arts organization called Arts Alive Chicago. She holds an MFA in Fiction Writing from Vermont College and has taught fiction and nonfiction writing at the Graham School of the University of Chicago. She recently retired from being a manuscript editor at the University of Chicago Press.

My favorite thing to do, in poems, is to write about what we often think of as commonplace and, through close observation, make accessible the extraordinary within them: to find the magic in everyday things. It’s easy to take the things, people, and animals around us for granted in a world where our attention is so often directed elsewhere. But I find that when I slow down and really pay attention to what’s around me, I am in awe of the complexities of nature or a bird or common moments or the people in my life. I take it as my job, as a poet, to try to put this awe into words for others who may not have taken notice of these things but realize, once I do find the right words, that this is just how they feel, too. In this way, I like to help others regain their own sense of wonder for the world. That sense of wonder is part of what keeps me young, I think. I am endlessly curious about the world around me.

2 Could you recommend a good essay about the craft of writing poetry?

To be honest, I’m not someone who often reads essays on craft—I tend, instead, to go directly to specific poems to try to figure out how the poet has created certain effects and/or handled a difficult subject. In essence, I guess I tend to learn by example. However, there is a Mary Oliver essay, titled “Sound,” that I found delightful and thought provoking. In it, she delineates the different families of sounds—including mutes, liquids, and aspirates—and the effect that these sounds have: “Now we see that words have not only a definition and possibly connotation, but also the felt quality of their own kind of sound” (A Poetry Handbook, p. 22). This is one of those things I think I’ve done for years—considering “the music” of a word—without the in-depth understanding of exactly what I was doing. I don’t think the essay changes how I write poems but it does, perhaps, give me a deeper understanding of what’s at work when I spend hours looking for precisely the right word in some line of a poem.

3 Is there a person whose life you’d like to capture in a poem?

What a timely question for me! I have actually been trying to write a poem about my mother’s 88-year-old cousin, whose life was incredibly difficult, in some ways, because of the cruel people around her. She could easily be bitter and mean-spirited, but when she recounts these stories, there is no hint of her feeling she’s been treated unfairly. She is matter of fact about the events and cruelties of her life, but chooses mostly to focus on the joys, from her little dog to her memories of family vacations in the woods of rural Wisconsin back in the 1940s. When I visited with her recently, she was barefoot and chattered on happily while making me the lunch she had insisted on preparing. The problem, in terms of writing a poem about her, is that I want to use every detail I know. Since I’m not planning on writing an epic poem, that clearly won’t do!

4 Should your readers “Google it” or do you need to clarify it in a note or epigraph?

I have employed notes following several poems, but those have been to indicate small passages quoted from other sources. In the main, I don’t think I tend to make too many obscure cultural references. That said, though, I guess I do expect readers to look up what they don’t know. I am sometimes surprised, however, that what I think is common knowledge might be new information to a reader. I happened on a short commentary about a recently published poem of mine in which the writer said: “And even Chet Baker we may only know through faint rumor. An old jazz singer? Blues?” It never occurred to me that anyone might not know who Chet Baker was.

5 Tell us about your latest poem.

I had read, not long ago, that scientists just discovered that giraffes hum at night. I also learned that some bats are known as whispering bats because of the low-intensity of their calls. I found both of these tidbits of information fascinating. Then, in August, my physician told me I had a heart murmur. Shortly thereafter, the lines “Giraffes hum. Bats whisper. / My heart murmurs” popped into my head. I walked around for several weeks with those two lines rattling in my brain until I finally sat down one day and wrote a little riff on my heart murmuring and what that might mean. The poem closes with musing about an echocardiogram. It is titled “Resound” in the sense of “to become filled with sound,” but also as in “about sound” (re: sound).

Yvonne Zipter is the author of the full-length collection The Patience of Metal (a Lambda Literary Award Finalist) and the chapbook Like Some Bookie God. Her poems have appeared in numerous periodicals over the years, including Poetry, Southern Humanities Review, Calyx, Crab Orchard Review, Metronome of Aptekarsky Ostrov (Russia), Bellingham Review, and Spoon River Poetry Review, as well as in several anthologies. Her poem “Osteosarcoma: A Love Poem,” originally published in Poetry, was reprinted in Writing and Understanding Poetry for Teachers and Students: A Heart’s Craft, edited by Suzanne Keyworth and Cassandra Robison. She is also the author of two nonfiction books: Diamonds Are a Dyke’s Best Friend and Ransacking the Closet. She is one of the founders of Hot Wire: A Journal of Women’s Music and Culture and a 1995 inductee into the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame. She received a fellowship to the Summer Literary Seminar in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 2004, an Illinois Arts Council Literary Award in 2001, and the Sprague/Todes Literary Award in 1997. Her published poems are currently being sold in two poetry-vending machines in Chicago, the proceeds from which are donated to a nonprofit arts organization called Arts Alive Chicago. She holds an MFA in Fiction Writing from Vermont College and has taught fiction and nonfiction writing at the Graham School of the University of Chicago. She recently retired from being a manuscript editor at the University of Chicago Press.

October 2019

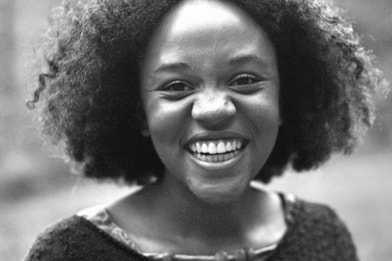

Crystal Boson

1 Is there a poem that comes back to you again and again? Why?

Honorée Fanonne Jeffer’s poem, "The Gospel of Barbeque" is the one I constantly think about and reread. About once a week actually. It is a work that reminds me of home, not just in terms of the South, but home as an idea of family that together land and legacy. There is a solid legacy of survival that is read through family that binds together and enacts practices that teach you to navigate a landscape, system, nation, and neighbors who desire to starve and drive you out. It is a poem that reminds me to survive, and laugh and dig deep. Every bit of that work is sound advice.

2 How important is reading a poem aloud?

Even though I often shy away from reading my work out loud, I think it is extremely important. Poems are spells that need to be spoken aloud to give them more life. When we read poems out loud, it lets us share them more widely and experience them in different ways. I think this is especially true for the "hard poems" we write. The poems that take the most from us to write need to be shared out loud. The extra effort of speaking them out makes them more powerful.

3 Do you subscribe to literary journals?

I actually don't right now, and I feel bad about it. After I left the academy and being a professor, I needed a break from everything creative and academic. I still am taking that break. It took me a while to get back to writing. I'm just not ready to dive back into the journals yet.

4 Is there a poetry resource that has helped you with your writing, or in getting published?

Yes. The best thing thing for my poetry has been going to the Rhode Island Writer's Colony. It was a place that gave me space to write without having to explain myself, my work, or my view point. It was fantastic to be in a space with other Black writers who were equally as serious about their craft as they were building community. This was the space where I wrote most of my collection "The Bitter Map". The RIWC gave me both space and a family and has been the absolute best thing for my writing.

5 How much time do you spend in the poetry world?

I'm just now starting to get back in. I've been happily asked to be on a board of "Paper Plains" and I'm getting to do readings again. I've also started writing a new collection. I'm really fortunate I'm getting this opportunity to come back in.

Crystal Boson writes short, dense poems that lay bare the complicated geographies of the United States and the lives of the Black, queer, and marginalized bodies that dwell within its boundaries. She currently writes about, and resides in the midwest. She is a Rhode Island Writer's Colony, Cave Canem and Callaloo fellow, and was awarded the Langston Hughes Creative Writing Award in 2014. She has work published in Blueshift Journal, Pank, Parcel, among other locations. Most recently her work: the bitter map was selected as the winner of the 2017 Honeysuckle Press Chapbook Contest by Saeed Jones. Videos of her reading, purchase information, and links to individually published works can be found on her website: crystalboson.com

Honorée Fanonne Jeffer’s poem, "The Gospel of Barbeque" is the one I constantly think about and reread. About once a week actually. It is a work that reminds me of home, not just in terms of the South, but home as an idea of family that together land and legacy. There is a solid legacy of survival that is read through family that binds together and enacts practices that teach you to navigate a landscape, system, nation, and neighbors who desire to starve and drive you out. It is a poem that reminds me to survive, and laugh and dig deep. Every bit of that work is sound advice.

2 How important is reading a poem aloud?

Even though I often shy away from reading my work out loud, I think it is extremely important. Poems are spells that need to be spoken aloud to give them more life. When we read poems out loud, it lets us share them more widely and experience them in different ways. I think this is especially true for the "hard poems" we write. The poems that take the most from us to write need to be shared out loud. The extra effort of speaking them out makes them more powerful.

3 Do you subscribe to literary journals?

I actually don't right now, and I feel bad about it. After I left the academy and being a professor, I needed a break from everything creative and academic. I still am taking that break. It took me a while to get back to writing. I'm just not ready to dive back into the journals yet.

4 Is there a poetry resource that has helped you with your writing, or in getting published?

Yes. The best thing thing for my poetry has been going to the Rhode Island Writer's Colony. It was a place that gave me space to write without having to explain myself, my work, or my view point. It was fantastic to be in a space with other Black writers who were equally as serious about their craft as they were building community. This was the space where I wrote most of my collection "The Bitter Map". The RIWC gave me both space and a family and has been the absolute best thing for my writing.

5 How much time do you spend in the poetry world?

I'm just now starting to get back in. I've been happily asked to be on a board of "Paper Plains" and I'm getting to do readings again. I've also started writing a new collection. I'm really fortunate I'm getting this opportunity to come back in.

Crystal Boson writes short, dense poems that lay bare the complicated geographies of the United States and the lives of the Black, queer, and marginalized bodies that dwell within its boundaries. She currently writes about, and resides in the midwest. She is a Rhode Island Writer's Colony, Cave Canem and Callaloo fellow, and was awarded the Langston Hughes Creative Writing Award in 2014. She has work published in Blueshift Journal, Pank, Parcel, among other locations. Most recently her work: the bitter map was selected as the winner of the 2017 Honeysuckle Press Chapbook Contest by Saeed Jones. Videos of her reading, purchase information, and links to individually published works can be found on her website: crystalboson.com

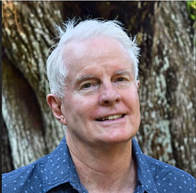

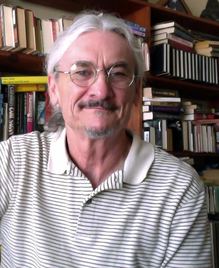

Glen Wilson

1 Is there a poem that comes back to you again and again? Why?

I'm a massive Heaney fan but its perhaps one of his lesser known poems Limbo that I find I return to again and again, its use of language is so sparse but accomplishes so much in it's narrative, It deals with the story of an illegitimate child and its mother in Ireland. How Heaney deftly handles this story shows why he is regarded so highly. Patrick Kavanagh's Epic is another touchstone poem for me, depending on the day it's one of those two. I also often find a line or couplet keep coming back to me more so than whole poems.

2 How important is reading a poem aloud?

I think you are missing out so much from a poem by it being simply a written form, to hear the aural richness of a great poem takes it to another level, even in terms of composing your own work it gives you a whole new set of tools to work with, it is more than just a proving ground. I also lead worship at my local church so the musicality of poetry is important to me

3 Do you subscribe to literary journals?

I currently have a subscription to The Moth magazine in Ireland, its a beautifully curated journal that has great selection of poems, short stories and artwork. Aside from that I tend to dip into an issue at a time to get an idea of what is out there, I have copies of Poetry Ireland review, The Stinging Fly, Southern Humanities Review and Rattle to name a few.

4 Is there a poetry resource that has helped you with your writing, or in getting published?

I was recommended an anthology of poetry called Staying Alive (Bloodaxe) that is a feast of poetics, there is so much to explore and get your teeth into, the editor Neil Astley has gathered a fantastic selection of the greats and lesser-known gems.

5 How much time do you spend in the poetry world?

I attend readings when I can but probably spend a lot more time conversing and engaging with other poets online via twitter, Facebook etc. I don't think I ever switch off from poetry, it's fairly intrinsic to my life so I'm always open to ideas and inspiration so I suppose in a sense my antenna is always tuned to the poetry world.

Glen Wilson lives with his wife Rhonda and two children in Portadown, Co Armagh, Ireland. He is Worship Leader at St Mark’s Church of Ireland Portadown. He studied English and Politics at Queens University Belfast and has a Post Grad Diploma in Journalism studies from the University of Ulster.

He has been widely published having work in The Honest Ulsterman, The Stony Thursday Book, Foliate Oak, Iota, the Interpreters House, Southword, The Ogham Stone, The Luxembourg Review, RAUM and The Incubator Journal amongst others. In 2014 he won the Poetry Space competition and was shortlisted for the Wasafiri New Writing Prize. He was shortlisted for the Seamus Heaney Award for New Writing 2016 and The 2016 Wells Festival of Literature. He won the Seamus Heaney Award for New Writing 2017 for his poem "The Lotus Gait" and the Jonahtan Swift Creative Writing Award in 2018.

In 2018 He was shortlisted for the Mairtin Crawford Poetry Award and the Hungry Hill Poets Meet Politics Competition, Clodhorick Poetry Competition, Leeds Peace Poetry Prize, and was highly commended in the iYeats Poetry Competition. In 2019 he won the Trim Poetry Competition, was shortlisted for the Strokestown international Poetry Competition, Doolin Writers Weekend and was highly commended in the Oliver Goldsmith Poetry Competition.

He has also been longlisted and commended in The National Poetry Competition, The Plough Prize, Segora Poetry Competition and the Welsh International Poetry Competition His first collection of poetry An Experience on the Tongue is out 2019 with Doire Press.

https://glenwilsonpoetry.wordpress.com/

Twitter @glenhswilson

https://www.doirepress.com/bookstore/poetry/

I'm a massive Heaney fan but its perhaps one of his lesser known poems Limbo that I find I return to again and again, its use of language is so sparse but accomplishes so much in it's narrative, It deals with the story of an illegitimate child and its mother in Ireland. How Heaney deftly handles this story shows why he is regarded so highly. Patrick Kavanagh's Epic is another touchstone poem for me, depending on the day it's one of those two. I also often find a line or couplet keep coming back to me more so than whole poems.

2 How important is reading a poem aloud?

I think you are missing out so much from a poem by it being simply a written form, to hear the aural richness of a great poem takes it to another level, even in terms of composing your own work it gives you a whole new set of tools to work with, it is more than just a proving ground. I also lead worship at my local church so the musicality of poetry is important to me

3 Do you subscribe to literary journals?

I currently have a subscription to The Moth magazine in Ireland, its a beautifully curated journal that has great selection of poems, short stories and artwork. Aside from that I tend to dip into an issue at a time to get an idea of what is out there, I have copies of Poetry Ireland review, The Stinging Fly, Southern Humanities Review and Rattle to name a few.

4 Is there a poetry resource that has helped you with your writing, or in getting published?

I was recommended an anthology of poetry called Staying Alive (Bloodaxe) that is a feast of poetics, there is so much to explore and get your teeth into, the editor Neil Astley has gathered a fantastic selection of the greats and lesser-known gems.

5 How much time do you spend in the poetry world?

I attend readings when I can but probably spend a lot more time conversing and engaging with other poets online via twitter, Facebook etc. I don't think I ever switch off from poetry, it's fairly intrinsic to my life so I'm always open to ideas and inspiration so I suppose in a sense my antenna is always tuned to the poetry world.

Glen Wilson lives with his wife Rhonda and two children in Portadown, Co Armagh, Ireland. He is Worship Leader at St Mark’s Church of Ireland Portadown. He studied English and Politics at Queens University Belfast and has a Post Grad Diploma in Journalism studies from the University of Ulster.

He has been widely published having work in The Honest Ulsterman, The Stony Thursday Book, Foliate Oak, Iota, the Interpreters House, Southword, The Ogham Stone, The Luxembourg Review, RAUM and The Incubator Journal amongst others. In 2014 he won the Poetry Space competition and was shortlisted for the Wasafiri New Writing Prize. He was shortlisted for the Seamus Heaney Award for New Writing 2016 and The 2016 Wells Festival of Literature. He won the Seamus Heaney Award for New Writing 2017 for his poem "The Lotus Gait" and the Jonahtan Swift Creative Writing Award in 2018.

In 2018 He was shortlisted for the Mairtin Crawford Poetry Award and the Hungry Hill Poets Meet Politics Competition, Clodhorick Poetry Competition, Leeds Peace Poetry Prize, and was highly commended in the iYeats Poetry Competition. In 2019 he won the Trim Poetry Competition, was shortlisted for the Strokestown international Poetry Competition, Doolin Writers Weekend and was highly commended in the Oliver Goldsmith Poetry Competition.

He has also been longlisted and commended in The National Poetry Competition, The Plough Prize, Segora Poetry Competition and the Welsh International Poetry Competition His first collection of poetry An Experience on the Tongue is out 2019 with Doire Press.

https://glenwilsonpoetry.wordpress.com/

Twitter @glenhswilson

https://www.doirepress.com/bookstore/poetry/

September 2019

Amirah Al Wassif

1 If you were Poet Laureate of the US, (or any country) what program(s) would you put forth?

There are many important issues, I would love to focus on it. these issues include cultural, social and these various obstacles which stand against our humanity. I would love to play a serious role in the society, not a fake role, I would love to tell all the people the truth, not the cliché speech which they used to listen. I would love to try my best to spread the spirit of poetry trough my position because I believe that the poetry power is the best motivation for nations.i believe that the secret of the successful program(s) is the honesty! If we are so honest and serious, if we believe in poetry, if we encourage people to read poetry, the world will be better.

I'm tempted to work on human rights issues and if I had such a chance, I would love also to support all those talented persons in many and different fields like literature, music, dancing, visual arts who never find the full support to start and complete their creative journey just because they don’t have enough money to study, to learn or to travel.

Maybe someone will name these programs "so dreamy", but insist saying that if we are honest enough, if we read more poetry, we will achieve what we want, and we will spread love and peace.

2 Some do, some say never. Have your poems that use a line from the poem as the title?

Yes, I have many poems which use a line as the title, for example, my poetry collection For Those Who Don’t Know Chocolate, and many poems of mine. Actually, I don’t plan to do that, I leave this to my feeling then, how I feel while writing the poem, if I felt that any line in the poem more suitable and sensitive enough to be the title, I gladly choose it and some times, something I don’t know what is that, whisper to my soul secretly by the title of the poem before discovering the rest of the poem, and how it will be in the end?

3 What has been the best advice you’ve received while attending a workshop?

The funny thing is that I didn’t attend any poetry workshop before. Actually, I loved to do that, but I didn’t have such a wonderful chance. and, the best advice I had received is from the great poet Maya Angelou, from her inspiring writing, she wrote: "if you are always trying to be normal, you will never know, how amazing you can be."

4 Could you share the first draft of a poem you’re working on now and tell us where you’re going with it?

Of course, this is my horrible first draft of my new poem which I am working on right now " how could Alexandria speaks poetry?"

I hope to finish it with a bit feeling of satisfaction, I just want to tell the world how I feel towards Alexandria and how poetic her voice is?

How could Alexandria speak poetry?

Alexandria represents herself as an excellent poet

sets on the top of the world, with curious eyes and merciful heart

dries her eternity hair with civilization towel

picks the obvious stars from the sky

whispers in a very warm tone " hello"

Alexandria hugs you like a sea

she knows how to get you a great piece of advice like a sea!

the poetic kingdom fulls of tears and smiles

Alexandria, the factory of butterflies

where each elegant butterfly was a perfect poem

All my age, I wonder how could Alexandria speak poetry?

how could that kingdom absorb me?

talk to my senses, to my bones

shared my heart perfectly??

Alexandria represents herself as an excellent poet

invents new words for describing the beauty

sets on the top of the world

uses its landscapes as a punctuations

catches the wet clouds by her magical eyes

and turns them into wondrous verses and miracles

but, she drives me truly insane

while wandering in her corners as a crazy fan

asking myself how could Alexandria speak poetry?

how could that kingdom absorb me?

and shared my heart perfectly??

5 Do you listen to music while writing a poem?

Absolutely, I listen to music while writing poetry, this is an essential part of my writing process, I also practice the meditation in the middle of my writing.

Amirah Al Wassif is a freelance writer, poet, and novelist. Five of her books were written in Arabic and many of her English works have been published in cultural magazines in many international literary and cultural magazines around the globe such as Praxis Magazine , A Gathering of the Tribes, Credo Espoir, Reach Poetry, Otherwise Engaged literature and arts journal, Cannon's Mouth, Mediterranean Poetry, The BeZine , Spillwords, Merak Magazine, Poetry Magazine, Writers Resist, the Bosphorus Review Of Books, the Writer NewSletter, Call and Response Journal, Echoes Literary Magazine, Better Than Starbucks, Envision Arts, Women of Strength Strong Courage Magazine, Chiron Review , the Conclusion Magazine and Street Light Press.

She has two published books in English, for those who don't know chocolate and a children's book the cocoa boy and other stories.

Her English literary creative works have been translated into Spanish, Arabic, Hindi, and Kurdish

There are many important issues, I would love to focus on it. these issues include cultural, social and these various obstacles which stand against our humanity. I would love to play a serious role in the society, not a fake role, I would love to tell all the people the truth, not the cliché speech which they used to listen. I would love to try my best to spread the spirit of poetry trough my position because I believe that the poetry power is the best motivation for nations.i believe that the secret of the successful program(s) is the honesty! If we are so honest and serious, if we believe in poetry, if we encourage people to read poetry, the world will be better.

I'm tempted to work on human rights issues and if I had such a chance, I would love also to support all those talented persons in many and different fields like literature, music, dancing, visual arts who never find the full support to start and complete their creative journey just because they don’t have enough money to study, to learn or to travel.

Maybe someone will name these programs "so dreamy", but insist saying that if we are honest enough, if we read more poetry, we will achieve what we want, and we will spread love and peace.

2 Some do, some say never. Have your poems that use a line from the poem as the title?

Yes, I have many poems which use a line as the title, for example, my poetry collection For Those Who Don’t Know Chocolate, and many poems of mine. Actually, I don’t plan to do that, I leave this to my feeling then, how I feel while writing the poem, if I felt that any line in the poem more suitable and sensitive enough to be the title, I gladly choose it and some times, something I don’t know what is that, whisper to my soul secretly by the title of the poem before discovering the rest of the poem, and how it will be in the end?

3 What has been the best advice you’ve received while attending a workshop?

The funny thing is that I didn’t attend any poetry workshop before. Actually, I loved to do that, but I didn’t have such a wonderful chance. and, the best advice I had received is from the great poet Maya Angelou, from her inspiring writing, she wrote: "if you are always trying to be normal, you will never know, how amazing you can be."

4 Could you share the first draft of a poem you’re working on now and tell us where you’re going with it?

Of course, this is my horrible first draft of my new poem which I am working on right now " how could Alexandria speaks poetry?"

I hope to finish it with a bit feeling of satisfaction, I just want to tell the world how I feel towards Alexandria and how poetic her voice is?

How could Alexandria speak poetry?

Alexandria represents herself as an excellent poet

sets on the top of the world, with curious eyes and merciful heart

dries her eternity hair with civilization towel

picks the obvious stars from the sky

whispers in a very warm tone " hello"

Alexandria hugs you like a sea

she knows how to get you a great piece of advice like a sea!

the poetic kingdom fulls of tears and smiles

Alexandria, the factory of butterflies

where each elegant butterfly was a perfect poem

All my age, I wonder how could Alexandria speak poetry?

how could that kingdom absorb me?

talk to my senses, to my bones

shared my heart perfectly??

Alexandria represents herself as an excellent poet

invents new words for describing the beauty

sets on the top of the world

uses its landscapes as a punctuations

catches the wet clouds by her magical eyes

and turns them into wondrous verses and miracles

but, she drives me truly insane

while wandering in her corners as a crazy fan

asking myself how could Alexandria speak poetry?

how could that kingdom absorb me?

and shared my heart perfectly??

5 Do you listen to music while writing a poem?

Absolutely, I listen to music while writing poetry, this is an essential part of my writing process, I also practice the meditation in the middle of my writing.

Amirah Al Wassif is a freelance writer, poet, and novelist. Five of her books were written in Arabic and many of her English works have been published in cultural magazines in many international literary and cultural magazines around the globe such as Praxis Magazine , A Gathering of the Tribes, Credo Espoir, Reach Poetry, Otherwise Engaged literature and arts journal, Cannon's Mouth, Mediterranean Poetry, The BeZine , Spillwords, Merak Magazine, Poetry Magazine, Writers Resist, the Bosphorus Review Of Books, the Writer NewSletter, Call and Response Journal, Echoes Literary Magazine, Better Than Starbucks, Envision Arts, Women of Strength Strong Courage Magazine, Chiron Review , the Conclusion Magazine and Street Light Press.

She has two published books in English, for those who don't know chocolate and a children's book the cocoa boy and other stories.

Her English literary creative works have been translated into Spanish, Arabic, Hindi, and Kurdish

Claus Ankersen

1 If you were Poet Laureate of the US, (or any country) what program(s) would you put forth?

Ah, thank you so much for asking this excellent question. I am actually working to import and introduce this fantastic concept to my country. What programs would I NOT launch as poet laureate, given the opportunity?

I would work to popularize and promote literature and poetry by making it widely accessible for the general public. I would promote and initiate programmes to publish poetry in nationwide newspapers and magazines, besides putting poetry on the curriculum in schools. Poetry installed as visual, site-specific artworks in the public space, throughout the country would be a welcome way to counter the commodification and capitalization of the public realm. I would also initiate programs to further local, regional and international networking and collaboration among poets, most notably I would work on strengthening Army of Poets, a global sister-brotherhood of hypersensitive pensters and a network of actionpoets and like minded, that I founded in 2015 to help connect poets and work together on making not only the voice of poetry heard, but also the voice of the poets – whose inspired and visual inputs are much needed in today’s world. Oh, I would do so many things. Seminars and colloquiums and festivals and talks and literatours and wordcaravans...Outreach must never be forgotten. Or the spoken word of performance poetry. The common denominator of all this would in a sense be ’the meeting’.

2 Some do, some say never. Have you poems that use a line from the poem as the title?

I guess I do both-and. Quite a few of my poems have a title that includes at least part of a line from the poem. A lot of poems have a title that refers to some aspect of the poems meaning or narrative, and then others again have titles that doesn’t directly refer to words or lines used in the poem. I might come off as literary naïve here, but frankly, I have never even heard of this controversy.

It reminds me a bit of the old page vs stage discussion, or the different opinions about performative use of the so-called poetic voice during live-readings. Different practices and opinions are fine. The detrimentally to the entire field of poetry arises when the differing opinions lead to fraktionism, exclusionism and elitism among the literary community. Something I have witnessed all over the world. We all think, this culture of envious squabble is a local or national thing, but the sad truth is that it happens all over. In every poetry community on the globe. Basically the poetry community is as divided and polarized as the rest of society, and affected by the same dynamics. We divide when we could unite. We repel when we could embrace. We hate when we could love. Working with Army of Poets and the practice of international literary ambassadorship is my way to counteract this. With the meeting. It all starts with the meeting. Lets meet. We need to unite.

3 What has been the best advice you’ve received while attending a workshop?

I think perhaps, technically, it wasn’t in a workshop, but during my University days, where the resident Head of Department asked an overly complex question, more a statement of scientific position than actual question, the same kind of question often heard at the very end of a literary panel-debate, and got the following reply from the legendary Norwegian ethnographer, Fredrik Barth who simply replied: As long as it looks savvy on paper. How’s that for killing a heckler. I never forgot that.

4 Could you share a first draft of a poem you’re working on now and tell us where you’re going with it?

I would love to. In my open docs, this one pops up. It is a work in progress and sort of a poets poem. Right now spurred by the title question, you asked, I just used an initial note in Danish ’Du må ikke tjene penge på digte’ , translated it and made it into the title with the original idea for the title added as a sub- or alternative title.

You mustn’t make money on poems

(We Built Our Legacy)

we build our legacy in stacks of books

others build digits on electronic accounts

accumulate afterlife in sculpture parks and on the walls

of hospital wings and university departments

we build our legacy channeling stories

chipping flints from the bedrock

human imagination

fishing for blue fish of illumination

chasing adventures

through pen, keyboard or microphone

in dance, play always and forever

we build our legacy in poetry

capturing snaphots of human rays

as they materialise as a kiss

between strangers united

on some square looking up

at miracles unfolding

the impossible in full, eternal bloom

natural as nature becoming

we build our legacy

we build our legacy

gazing at the stars

reading between the lines

with every breath, we build our legacy

with every kiss, we seal the deal

with every dance, we celebrate the fruits

of the loins of creation

we spring our legacy fountainesque

with every letter

we build our legacy

in the beginning

the word.

5 Do you listen to music while writing a poem?

Well, I am afraid I’ve gotta hit the both-and button once again here. Sometimes I do and sometimes I don’t. It all depends on the material, my mood, the time of day...many things.

When I wrote as a teenager it would almost always be to music. Dance music and upbeat disco and pop music would enable me to ride on the energy and pace of the music, without being distracted, as I would be if I were to listen to jazz and loosing the creative flow for a musical one, starting to whistle or drum my knees. Later in my writing career, and during my time in university, I have written a lot in silence. I like that too. Now I do both. This November I will see publication of Pink Pong Poetry (forthcoming on Editura FrACTalia, 2019), a trilingual collaborative collection of poetry written to Pink Floyd songs by Romanian poet Andrei Zbirnea and myself. This fusion of worlds have produced a truly trippy collection, which I think many people will enjoy. It will come out in English, Romanian and Danish, and I hope reading it will inspire more people with experimenting working with music as jumpstarter in writing sessions. Big Magic is there, poet.

Claus Ankersen, intergalactic traveler, poet, writer, artist, anthropologist and performer, is the author of 12 books of prose and poetry. A world leading voice in performance poetry, Claus has performed readings of his literature and poetry at festivals in 20 countries around the world. The author works bilingually in Danish and English, his work ranging from poetry and short stories to longer fiction, and deals with such themes as esoterics, systems-critique, love, r/evolution and magical reality. Often likened to such luminaries as Alan Ginsberg, Dan Turell, James Joyce and Hunter S. Thompson, Ankersen offers a fresh perspective all his own. Published internationally, his work translated into 12 languages, Ankersen shares his treasure-chest of perpetually blooming wonder across numerous continents. His merging of cross-disciplinary works comes from a range of sources, including those of the site-specific, psycho-geography of inner and outer landscapes. Recent publications include the full poetry collections Cantecul Tigrului/ Song of the Tiger (Editura Fractalia, 2019), in defense of the cherries (Brumar, 2019), Grab Your Heart And Follow Me (Poetrywala/Paperwall, 2018, Soulmates (Copenhagen Storytellers, 2017), A Sudden Convergence (Krok Books, 2016), as well as the picaresque novel Pendæmonium (Det Poetiske Bureau, 2018), contributions to two Indian international poetry anthologies, Capitals (Bloomsbury, 2017), All The Worlds Between (Yoda Press, 2017), two American anthologies; The van Gogh tribute Resurrection of a Sunflower (Pski’s Porch Publishing, 2017) and Insert Yourself Here (The Paragon Journal Press, 2017) as well as Cleptohydra ALMANAH, a Romanian anthology on the river Danube (Lower Danube Cultural Center). Latest performance-venues include Bucharest International Poetry Festival, Faine Misto Festival in Ukraine and TEDxCopenhagen. India holds a special place in this poet's heart. In India, Claus holds fellowships from Sangam House, Studio Arnawaz, and CMI Arts Initiative, and has appeared at Poetry with Prakriti, Delhi Arts Festival, Kala Ghoda Festival, as well as given guest lectures at Universities and learning institutes. Having met and interacted with poetry colleagues and titans across the world, Claus Ankersen has realized the need for a formal organization of the global-local sister-brotherhood of hypersensitive pens, most recently founding the activist artist network Army of Poets. When he is not writing poetry, traveling or making art, Claus is developing his own mystery school of yoga and magic, cooking and talking back to nature.

Ah, thank you so much for asking this excellent question. I am actually working to import and introduce this fantastic concept to my country. What programs would I NOT launch as poet laureate, given the opportunity?

I would work to popularize and promote literature and poetry by making it widely accessible for the general public. I would promote and initiate programmes to publish poetry in nationwide newspapers and magazines, besides putting poetry on the curriculum in schools. Poetry installed as visual, site-specific artworks in the public space, throughout the country would be a welcome way to counter the commodification and capitalization of the public realm. I would also initiate programs to further local, regional and international networking and collaboration among poets, most notably I would work on strengthening Army of Poets, a global sister-brotherhood of hypersensitive pensters and a network of actionpoets and like minded, that I founded in 2015 to help connect poets and work together on making not only the voice of poetry heard, but also the voice of the poets – whose inspired and visual inputs are much needed in today’s world. Oh, I would do so many things. Seminars and colloquiums and festivals and talks and literatours and wordcaravans...Outreach must never be forgotten. Or the spoken word of performance poetry. The common denominator of all this would in a sense be ’the meeting’.

2 Some do, some say never. Have you poems that use a line from the poem as the title?

I guess I do both-and. Quite a few of my poems have a title that includes at least part of a line from the poem. A lot of poems have a title that refers to some aspect of the poems meaning or narrative, and then others again have titles that doesn’t directly refer to words or lines used in the poem. I might come off as literary naïve here, but frankly, I have never even heard of this controversy.

It reminds me a bit of the old page vs stage discussion, or the different opinions about performative use of the so-called poetic voice during live-readings. Different practices and opinions are fine. The detrimentally to the entire field of poetry arises when the differing opinions lead to fraktionism, exclusionism and elitism among the literary community. Something I have witnessed all over the world. We all think, this culture of envious squabble is a local or national thing, but the sad truth is that it happens all over. In every poetry community on the globe. Basically the poetry community is as divided and polarized as the rest of society, and affected by the same dynamics. We divide when we could unite. We repel when we could embrace. We hate when we could love. Working with Army of Poets and the practice of international literary ambassadorship is my way to counteract this. With the meeting. It all starts with the meeting. Lets meet. We need to unite.

3 What has been the best advice you’ve received while attending a workshop?

I think perhaps, technically, it wasn’t in a workshop, but during my University days, where the resident Head of Department asked an overly complex question, more a statement of scientific position than actual question, the same kind of question often heard at the very end of a literary panel-debate, and got the following reply from the legendary Norwegian ethnographer, Fredrik Barth who simply replied: As long as it looks savvy on paper. How’s that for killing a heckler. I never forgot that.

4 Could you share a first draft of a poem you’re working on now and tell us where you’re going with it?

I would love to. In my open docs, this one pops up. It is a work in progress and sort of a poets poem. Right now spurred by the title question, you asked, I just used an initial note in Danish ’Du må ikke tjene penge på digte’ , translated it and made it into the title with the original idea for the title added as a sub- or alternative title.

You mustn’t make money on poems

(We Built Our Legacy)

we build our legacy in stacks of books

others build digits on electronic accounts