SoFloPoJo Contents: Home * Essays * Interviews * Reviews * Special * Video * Visual Arts * Archives * Calendar * Masthead * SUBMIT * Tip Jar

May 2024 Interviews

|

Dorianne Laux & AE 'Earl' Hines

with Lenny DellaRocca hosted by Judy Ireland Discussing poetry written in her Monday Workshop: Dorianne Laux: “The last one we wrote, Earl, this last Monday was one that I pulled a phrase from one of the poems in your book – I think it was the last one you read: “I did die that summer”... (from AE Hines poem: “Sacramento 1994) AE “Earl” Hines: “Well you know what’s ironic about that, I wrote that poem after reading “Bakersfield 1969” (by Dorianne Laux) Dorianne Laux: “Are you kidding?!” We invite you to view the video for more. |

|

Dorianne Laux in conversation with AE "Earl" Hines & Lenny DellaRocca

hosted by Judy Ireland, SoFloPoJo Reading Series Producer

see more of Dorianne Laux and AE Hines here:

https://www.southfloridapoetryjournal.com/sfpj-video-2024-25.html

hosted by Judy Ireland, SoFloPoJo Reading Series Producer

see more of Dorianne Laux and AE Hines here:

https://www.southfloridapoetryjournal.com/sfpj-video-2024-25.html

February 2024 Interviews

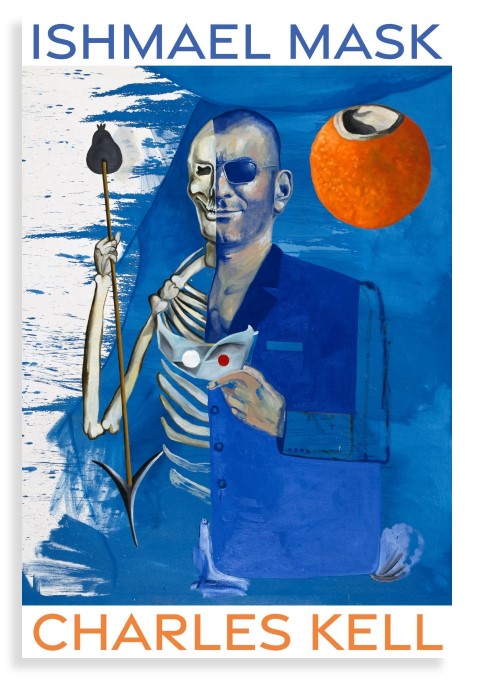

The Wanderer’s Embrace: A Conversation With Charles Kell

You can read W.J. Herbert's review of Charles Kell's Ishmael Mask at

https://www.valpo.edu/valparaiso-poetry-review/2023/12/18/charles-kell-review-by-w-j-herbert/

Neither Charles Kell nor I knew each other when I first reached out to him, but Autumn House Press had just published his award-winning debut collection, Cage of Lit Glass, and I was hoping to speak to him privately about the process. Because he was so unfailingly generous with his time, I hoped that when his new collection came out, we could discuss that one, too. Miguel Murphy describes Ishmael Mask as “tender, gothic, and wonderfully catastrophic,” and I heartily agree. In the conversation that follows, Kell and I talk about his creation of the collection: his artistic wanderings through its obsessions, absurdities, and passions. - W.J. Herbert

_____________________________________________________________

W.J. Herbert: Charles, Thanks so much for taking the time to talk with me and congratulations on this second collection! In your first, the award-winning Cage of Lit Glass, the book itself functions as a cage whose lit glass we peer through as we read, the poems “Words describing eyes written in a book/of glass.” In your newest collection, Ishmael Mask, the speaker has almost lost the ability to see. “I saw my face reflected from a metal/cup—black circles where my eyes/should be—open, dark. Is this a fundamental difference between the two collections? If so what, if any, explorations in Cage of Lit Glass and/or your prize-winning chapbook Pierre Mask [SurVision Books, 2021] led to this shift?

Charles Kell: First, thank you, truly, Wendy, for these insightful and deep questions. In Cage I was really trying to write the poems that were anathema to me, that made me uncomfortable, really, sick to my stomach, and were the opposite of what I was previously doing, how I started to write poems. I thought it might be the only book I do, so I wanted to put everything in them. The book works as a cage in some ways—many of the speakers are trapped in various physical, emotional, psychological enclosures, but there are many openings, chances for escape as well. In some ways the book is a cenotaph. I wanted to think about experiences, situations, friends, time, periods that are over. The book is filled with intertextual engagements and allusions—there are a handful of poems that take titles from and reference Kafka. However, the fundamental themes are incarceration, substance abuse, and a wreck my friends were in in 1999. Ishmael Mask, on the other hand, is not as concerned with the past, with “friends” as deeply, with thinking through certain “narrative” experiences. I was playing around much more, having fun through the lenses of Melville, Tomaž Šalamun; again, there are multiple intertextual relations but I was not concerned with constructing more straight-forward narrative poems. Though, there are many in there. I am constantly at odds. That is, I do like narrative poetry but I get bored quickly. An entire book (my own) of narrative poetry loses me. The poems lose the “punch” after so many in a row. Sometimes I think “just write a short story already.” Similarly, I love experimental, nonnarrative, surreal poetry where there are not clear footholds, but in the same way after so many in a row, I get lost, bored. I like a mix of both. Timothy Liu recently said he prefers my poems where I “lift my mask” and reveal more of myself. I took this to mean more narrative poems, or poems that have an intense, personal element, perhaps. I’m not sure or doubt that, for me at least, the more straightforward narrative poems lift any mask at all. It’s simply another mask; it’s just another persona relating this narrative moment. Maybe most nonnarrative poems feel closer to me, while the so-called “confessional” poems feel like another person. However, this was / is the advice I desperately needed to hear—it was so insightful. I took it to heart. At times, I can get lost with disparate voices, references, making poems “too cute.” I have a pantoum, “Titorelli,” referencing the court painter in Kafka’s The Trial; I like the poem but I don’t know if it’s a good poem; I don’t know, or I don’t think it’s really saying anything. I think what Tim Liu was telling me, reiterating, was to continue to write the hard stuff, the extremely difficult stuff that I, I admit, run from often. I love dark places but I don’t want to live in them. But I need to continue to go there…this was such helpful feedback, it actually helps me rethink and refocus on what I want to do.

WJH: In both collections, the act of writing and drawing figures prominently. In “The Carcasser” from Cage of Lit Glass, the speaker has “picked at the bodies of both living & dead,” as if his writing constructed by taking a body, “Ripping it open & then sticking/a pencil in the ribs to dig around.” As the speaker remarks in “Oblivion Letter,” the process is inward-looking: “Words you write when your shadow arrives.”

But in Ishmael Mask, the focus of the writing shifts outward, as in “Frames,” in which the speaker concludes, “…that one can draw/ loss, draw frost without anyone knowing//what it is, draw the color of night, draw—/for the final time—the light reaching the trees into nowhere.” Is a different ontological definition reflected in this shift?

CK: Writing and drawing, painting, novels and poetry—these are my life. Everything is a Künstlerroman for me. In Cage I was coming to terms and thinking through poems with subject matter that was not wholly mine. I was driving back to Marc’s house from the bar, back in 2016, and I showed him my story, “An Emptying”; he read it in the car and was silent then started joking—“here’s my carcass, my body, pick me clean”—and we laughed, howling out the windows. Most often, writing, books are all a person has, say, in jail / prison, in a small apartment, off somewhere alone; writing and books in Cage serve a specific purpose of thinking through these people and experiences. That if I could write it, get it down…I don’t know, it would simply “be all down.” It doesn’t change anything. Poetry, art, doesn’t do anything, change things about life. But I go back and forth with this. It changed my life in many ways. It means everything to me. I honestly don’t think I’d be here if not for these things. I worried in Cage about writing: am I using people? Am I simply turning horrific experiences into neat poems, couplets and quatrains? And, the answer, I guess, is yes. I was hoping not to do this as much in Ishmael, not for any reason other than “I already did that,” but there are many narrative poems in the new book. It’s subjective, in that I don’t want another poem going over the same material, subject matter. I just get bored with it in my own work. So, the philosophical shift, difference in definition, is one dealing with time and practice of poems. The drawing, the writing in Cage was much more focused on interiority, taking thoughts, feelings I’ve had for twenty years and seeing if I could construct these poems I wanted to make. I wanted Ishmael to be different, even though there are similarities. I wanted the writing, the drawing to focus on the present, the acts of writing in and for the moment. Now, I want to go further, in different directions.

WJH: Some of the writing in Ishmael Mask comes directly from the 19th century. The collection’s third poem, “Monsieur Melville” begins with contemporary lexicon, but it’s second quatrain quotes from Moby-Dick, “All right, sir, are your papers in order?/Is it a nag or a whaler?” How were you able to so successfully integrate 19th century ontological concerns and specific language with your 21st century perspective and approach to language?

CK: I am obsessed with the filmmaker, Nina Menkes. Dissolution (2010), her adaptation of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment is one of my favorite films. An earlier film, The Great Sadness of Zohara (1983) opens with a stirring quote from The Book of Job, and this film had such an impact on me. Biblical language influences me a great deal, though I’m not a believer. I love dearly nineteenth-century American literature, Hawthorne, Emerson, Thoreau, Melville, Dickinson. Initially, there was so much more language, other poems with that type of diction—I became overzealous. Miguel Murphy said I needed to take some out, that it wasn’t working. I trust him completely. All of those novels, that writing is still so relevant, so concerned with life. The poet, the artist is a wanderer, always looking for something, always trying out new things, knowing the whole time, that he/she/they will probably never find it. One becomes the act, the practice. I love the language of those books, the twisting, labyrinthine sentences, and how thoughts and philosophy accrues. Those books are worlds unto themselves. I wanted to integrate, interweave, and experience the language in my poems. Back to drawing, writing: many if not all the poems are love letters to my artistic obsessions. In my new work, I’m hoping to focus and think through some of the films of Nina Menkes, the films of Chantal Akerman.

WJH: Is there a parallel between the Pequod’s futile search for Moby-Dick and the speaker’s journey in Ishmael Mask? Are the unknowable “whale cathedrals” in your poem “Ambergris,” indicative of this?

CK: Ha! I love this question so much! Art is paradox, endless contradiction. Poems, novels, paintings—they are obviously journeys…but toward what, I have no idea. I think art is futile in some sense, but, again, for me, it is the most important thing. How do I reconcile with feeling that poetry and art make nothing happen, while dedicating my life to it, with thinking I wouldn’t be here if not for these things? I’m with Ishmael all the way on the Pequod. There is a “damp, drizzly November” within me, that it’s “high time to get to sea as soon as I can.” I honestly don’t think I write / read to stave off ennui, malaise, but maybe there is something there. Maybe it works that way on a much more unconscious level than Ishmael’s. I love his feelings, his sentiment. I have a confession: maybe I am, in my heart, a Romantic? I want the same things Ishmael wants. The search for the whale is different for Ishmael than it is for Ahab. I have no whale. As for the speaker’s journey(s) in Ishmael Mask—he’s simply a wanderer as well; he’s looking with no clear purpose, no ultimate direction in mind. Maybe running and leaving and hiding a bit.

WJH: Ishmael Mask contains a number of poems that seem to mock their speaker. In “Queequeg Mask,” the speaker carves a coffin and then lies inside, as did Moby-Dick’s Queequeg. The poem’s concluding lines quote Melville directly: “if a man made up his mind to live,/ mere sickness could not kill him.” A speaker’s hubris appears again in “Memnon Stone, Terror Stone.” Here, the character Pierre has challenged a stone to fall on and kill him and, when it doesn’t, he stands “haughtily on his feet,/as he owed thanks to none, and went/on his moody way.” In a final example, the speaker seems to mock himself as he dreams of a “wine-dark” sea; he, the heroic Odysseus, his prison cell, a ship. Can you explain whether these poems are meant to be read ironically? And, if so, how do they function in the collection?

CK: Initially I thought Ishmael Mask to be much more insouciant, playful, funnier than Cage. Some folks have said this is not really so. I thought the speakers in these poems, though serious at times, were also winking and giggling. There is a self-mockery when I find I’m taking myself too seriously. It’s serious but it’s also a joke. I love gallows’ humor, the most inappropriate joking, etc. The darkest places are the funniest, the silliest, where the most absurd things happen. I mean, for me, the very act of writing a poem is absurd. It’s complete hubris—“I have something to say, etc.” There are so many poems, so much art in the world, to think that I dare add to that—ha. There must be this acknowledgment of hubris, too, in a way. That one must think on the complete flip side, that one does have something new to say, that yes…I can add to this history. Even though it will all be forgotten in the near future. It’s the absurdity of creation that I find so lovely and intriguing. The complete dedication, the belief in oneself, the complete commitment to something that will soon be washed out to sea. I love it! So, there’s irony, there’s absurdity; dark humor, laughter; however, my absurdity is also my seriousness, that is, this is generally how I feel, think, believe.

WJH: Cage of Lit Glass, Pierre Mask, and Ishmael Mask are all image-rich, and no image in them is more intriguing to me than that of floating. In Cage’s “Bodybuilder,” the speaker says: “I can become something else./Take my eyes outside, let them float/overhead.” The opening lines of the third section’s “The Lost Boy,” begin: “Headless statues float in a broken/open Cornell box…”

In Ishmael Mask, the floating seems to have taken on an entirely different quality. In “Ohio”, it seems whimsical: “Later, we huddle in// the flooded basement, watching//the washing machine float by./We call it a chapel.” And though the poem “Frames,” will reach a darker conclusion, its initial buoyancy seems almost magical: “For the moment we are floating/out on one of the black/islands you describe so clearly, serene,/comfort, you say…” Do you think this change describes a shift in the speaker’s orientation?

CK: I was five years old, in my parents’ house, walking back to my room over brown carpet when I suddenly realized, huh, this life is all there is, there is nothing else. I didn’t feel sad, glad, or really anything at all at this moment. Who knows? Maybe I’m wrong? But my whole life I’ve felt like I’ve been floating along, that I’m both here and not really here. I then try to stay in the moment, be as present as I possibly can, and that works a little. But when I’m reading, writing I feel as if it’s not really happening. Sitting in a jail / prison cell back in 2006 / 2007, sitting in rehab, or even visiting a loved one in hospital—things that seem “really real” were strange, as though I were floating along the whole time. I’m not making sense, I know. Carrie and I just returned from hiking in Vermont. It was such an amazing time. I’m walking up this mountain, stepping on rocks, but it’s still as though part of me is not there. I am so tickled you pointed those moments out to me. I’m thinking now, damn, I should have edited some of the “floating stuff” but it’s how I’ve always felt and I can’t get outside of it. Ishmael is a floating character; Pierre is a character who floats. Bartleby is a cloud. All of Kafka’s characters are individuals who float. Beckett’s characters are floating voices.

WJH: Both of your collections, toward their conclusions, include a poem set in what might be considered an Elysium. The first, “Tower of Birds” is takes place in a garden with swans circling, beetles sleeping, and a speaker who is “made of earth, cool /moss” covering his feet. The second setting is wilder: a field somewhere in Kansas where water is absent, but hoped for and a missing person is sought. In both poems, the speaker is accompanied, and I wonder if you might talk about the difference between the speaker’s companions in poems which conclude very differently.

CK: I spend a good deal of time alone. I love being alone and crave solitude. Many of my poems feature lone speakers in lonely environments. On the flip side, I love people. People are so beguiling, frustrating, strange, horrible, cruel and also caring, compassionate; people are simultaneously boring yet wildly unpredictable; people are just so damn weird—I’m stating the obvious here. Often, I think, the poet is all Id, all animal and wild, complete monomaniacal (like Ahab!), me me me, the “I,” etc., whereas the novelist is more Ego, more concerned, ultimately, with the lives of people. I don’t really believe this and think it much more diffuse, complicated than my bad dichotomy. I know poets who care much more about the world of people than some novelists. A fiction writer I love, David Markson, often has solitary speakers in his later work. So, I can poke holes in that thought…. “Tower of Birds” is a love poem for Carrie. Timothy Liu challenged me—years ago—to write a love poem and that was it. Carrie is really the only person I spend a lot of time with. We can hang out and talk seriously, be silly, and also not talk at all— we can both do our own things. That poem is set in the Toledo Botanical Garden, a place we used to visit often. Carrie has saved me in too many ways to relate. “Amerika” is a different type of love poem; Kafka, I feel, has been there for me for such a long time, a lot of times when others have not. That’s a wandering, searching, “road” poem. Try to find Kafka, but he’s here all along in the books. I’m thinking of Kafka’s Amerika, or The Man Who Disappeared (1927), Karl Rossman, who gets exiled to America and ends up working in a circus in Oklahoma. I’m also thinking of Martin Kippenberger’s glorious installation, The Happy End of Franz Kafka’s Amerika (1994). Before I went to college—I didn’t go to college right away—I worked in a factory for a number of years, there were these names that seemed to float in the air—Kafka, Dostoevsky, Chekhov—and I went to the library and grabbed these books and devoured them. Kafka was always there and not there, too. I spend a part of each day thinking about Kafka; I often quote another favorite writer, László Krasznahorkai: “When I am not reading Kafka I am thinking about Kafka. When I am not thinking about Kafka I miss thinking about him. Having missed thinking about him for a while, I take him out and read him again. That’s how it works.” Kafka is, though, “the man who disappeared,” and that poem is the search. I always thought and argued that all of my “companion” poems are love poems.

WJH: The speaker of Ishmael Mask yearns for connection, and the act of writing seems to be a primary vehicle. In “Perfume,” the initials carved in a tree are “…love letters we scrawling on cedar…”

The speaker in the poem “Carrie” is anchored by sketched images: “For thirteen years/I’ve floated in the atmosphere//ready to burst, the brown strands/of your hair keeping me there.//All this time I’ve been drawing you.” You have said that there is no more optimistic act than writing a poem. Are the references to writing and drawing which are prevalent in this collection evidence of that?

CK: I believe in my bones that there is no more optimistic act than writing a poem, drawing a picture, playing music, practicing and creating any type of art. Writing is everything; every text, to me, is a letter of some sort, an epistle. I’ve written letters all my life, and still do, albeit less frequently. I wonder, often, are prisoners the last letter writers? The very act, the time, the commitment it takes to piece and stitch a manuscript together, it’s such an act of love, of devotion and optimism; also, no book is ever made in a vacuum, books are always acts of collaboration. Now, one might have 5-10 readers (way too many, in my opinion—but whatever works), or one might have a single reader, one person who helps. Cage was written intensely and with Peter Covino and Timothy Liu, with great help from them, and also with Christine Stroud, my wonderful editor at Autumn House Press. With Ishmael, I wanted to do something different; this book is Miguel Murphy’s book; he was really the only person other than Christine, who closely helped out. I was visiting my mother last August (2022), and Miguel would talk to me for hours on the phone, editing, reordering, cutting and revising. I listened to every damn word, mostly. Working on these books with these people are such acts of trust and love. These things are profoundly optimistic. All the poems are love letters, in many ways, each poem can be viewed as an ars poetica; they’re poems about poems, art, literature.

WJH: How, if at all, does your teaching as an assistant professor of English at The Community College of Rhode Island, as well as your work as editor of The Ocean State Review, nourish your life as a poet?

CK: The best part of working on the Ocean State Review is talking with other poets, writers, artists. I’ve made friends through this journal. I love discovering new poets and new work. Talking poetry, writing. When I took over the journal in 2015, the first poets I contacted for work were Michael Palmer and Medbh McGuckian—and they responded, with poems! I opened the 2016 issue with poems by Keith Waldrop and Rosmarie Waldrop. I also like to place poems, essays by writers who have never published before. I always joke about working on journals and presses: the hours are forever and the pay is nothing. Working on a journal or press is such a labor of love. In a completely different way I feel teaching informs. Not so much discovering new work but being around people. It’s always wonderful when a student gets excited by a poem, a story.

WJH: Thank you so much, Charles, for taking the time to speak with me!

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

W.J. Herbert: Charles, Thanks so much for taking the time to talk with me and congratulations on this second collection! In your first, the award-winning Cage of Lit Glass, the book itself functions as a cage whose lit glass we peer through as we read, the poems “Words describing eyes written in a book/of glass.” In your newest collection, Ishmael Mask, the speaker has almost lost the ability to see. “I saw my face reflected from a metal/cup—black circles where my eyes/should be—open, dark. Is this a fundamental difference between the two collections? If so what, if any, explorations in Cage of Lit Glass and/or your prize-winning chapbook Pierre Mask [SurVision Books, 2021] led to this shift?

Charles Kell: First, thank you, truly, Wendy, for these insightful and deep questions. In Cage I was really trying to write the poems that were anathema to me, that made me uncomfortable, really, sick to my stomach, and were the opposite of what I was previously doing, how I started to write poems. I thought it might be the only book I do, so I wanted to put everything in them. The book works as a cage in some ways—many of the speakers are trapped in various physical, emotional, psychological enclosures, but there are many openings, chances for escape as well. In some ways the book is a cenotaph. I wanted to think about experiences, situations, friends, time, periods that are over. The book is filled with intertextual engagements and allusions—there are a handful of poems that take titles from and reference Kafka. However, the fundamental themes are incarceration, substance abuse, and a wreck my friends were in in 1999. Ishmael Mask, on the other hand, is not as concerned with the past, with “friends” as deeply, with thinking through certain “narrative” experiences. I was playing around much more, having fun through the lenses of Melville, Tomaž Šalamun; again, there are multiple intertextual relations but I was not concerned with constructing more straight-forward narrative poems. Though, there are many in there. I am constantly at odds. That is, I do like narrative poetry but I get bored quickly. An entire book (my own) of narrative poetry loses me. The poems lose the “punch” after so many in a row. Sometimes I think “just write a short story already.” Similarly, I love experimental, nonnarrative, surreal poetry where there are not clear footholds, but in the same way after so many in a row, I get lost, bored. I like a mix of both. Timothy Liu recently said he prefers my poems where I “lift my mask” and reveal more of myself. I took this to mean more narrative poems, or poems that have an intense, personal element, perhaps. I’m not sure or doubt that, for me at least, the more straightforward narrative poems lift any mask at all. It’s simply another mask; it’s just another persona relating this narrative moment. Maybe most nonnarrative poems feel closer to me, while the so-called “confessional” poems feel like another person. However, this was / is the advice I desperately needed to hear—it was so insightful. I took it to heart. At times, I can get lost with disparate voices, references, making poems “too cute.” I have a pantoum, “Titorelli,” referencing the court painter in Kafka’s The Trial; I like the poem but I don’t know if it’s a good poem; I don’t know, or I don’t think it’s really saying anything. I think what Tim Liu was telling me, reiterating, was to continue to write the hard stuff, the extremely difficult stuff that I, I admit, run from often. I love dark places but I don’t want to live in them. But I need to continue to go there…this was such helpful feedback, it actually helps me rethink and refocus on what I want to do.

WJH: In both collections, the act of writing and drawing figures prominently. In “The Carcasser” from Cage of Lit Glass, the speaker has “picked at the bodies of both living & dead,” as if his writing constructed by taking a body, “Ripping it open & then sticking/a pencil in the ribs to dig around.” As the speaker remarks in “Oblivion Letter,” the process is inward-looking: “Words you write when your shadow arrives.”

But in Ishmael Mask, the focus of the writing shifts outward, as in “Frames,” in which the speaker concludes, “…that one can draw/ loss, draw frost without anyone knowing//what it is, draw the color of night, draw—/for the final time—the light reaching the trees into nowhere.” Is a different ontological definition reflected in this shift?

CK: Writing and drawing, painting, novels and poetry—these are my life. Everything is a Künstlerroman for me. In Cage I was coming to terms and thinking through poems with subject matter that was not wholly mine. I was driving back to Marc’s house from the bar, back in 2016, and I showed him my story, “An Emptying”; he read it in the car and was silent then started joking—“here’s my carcass, my body, pick me clean”—and we laughed, howling out the windows. Most often, writing, books are all a person has, say, in jail / prison, in a small apartment, off somewhere alone; writing and books in Cage serve a specific purpose of thinking through these people and experiences. That if I could write it, get it down…I don’t know, it would simply “be all down.” It doesn’t change anything. Poetry, art, doesn’t do anything, change things about life. But I go back and forth with this. It changed my life in many ways. It means everything to me. I honestly don’t think I’d be here if not for these things. I worried in Cage about writing: am I using people? Am I simply turning horrific experiences into neat poems, couplets and quatrains? And, the answer, I guess, is yes. I was hoping not to do this as much in Ishmael, not for any reason other than “I already did that,” but there are many narrative poems in the new book. It’s subjective, in that I don’t want another poem going over the same material, subject matter. I just get bored with it in my own work. So, the philosophical shift, difference in definition, is one dealing with time and practice of poems. The drawing, the writing in Cage was much more focused on interiority, taking thoughts, feelings I’ve had for twenty years and seeing if I could construct these poems I wanted to make. I wanted Ishmael to be different, even though there are similarities. I wanted the writing, the drawing to focus on the present, the acts of writing in and for the moment. Now, I want to go further, in different directions.

WJH: Some of the writing in Ishmael Mask comes directly from the 19th century. The collection’s third poem, “Monsieur Melville” begins with contemporary lexicon, but it’s second quatrain quotes from Moby-Dick, “All right, sir, are your papers in order?/Is it a nag or a whaler?” How were you able to so successfully integrate 19th century ontological concerns and specific language with your 21st century perspective and approach to language?

CK: I am obsessed with the filmmaker, Nina Menkes. Dissolution (2010), her adaptation of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment is one of my favorite films. An earlier film, The Great Sadness of Zohara (1983) opens with a stirring quote from The Book of Job, and this film had such an impact on me. Biblical language influences me a great deal, though I’m not a believer. I love dearly nineteenth-century American literature, Hawthorne, Emerson, Thoreau, Melville, Dickinson. Initially, there was so much more language, other poems with that type of diction—I became overzealous. Miguel Murphy said I needed to take some out, that it wasn’t working. I trust him completely. All of those novels, that writing is still so relevant, so concerned with life. The poet, the artist is a wanderer, always looking for something, always trying out new things, knowing the whole time, that he/she/they will probably never find it. One becomes the act, the practice. I love the language of those books, the twisting, labyrinthine sentences, and how thoughts and philosophy accrues. Those books are worlds unto themselves. I wanted to integrate, interweave, and experience the language in my poems. Back to drawing, writing: many if not all the poems are love letters to my artistic obsessions. In my new work, I’m hoping to focus and think through some of the films of Nina Menkes, the films of Chantal Akerman.

WJH: Is there a parallel between the Pequod’s futile search for Moby-Dick and the speaker’s journey in Ishmael Mask? Are the unknowable “whale cathedrals” in your poem “Ambergris,” indicative of this?

CK: Ha! I love this question so much! Art is paradox, endless contradiction. Poems, novels, paintings—they are obviously journeys…but toward what, I have no idea. I think art is futile in some sense, but, again, for me, it is the most important thing. How do I reconcile with feeling that poetry and art make nothing happen, while dedicating my life to it, with thinking I wouldn’t be here if not for these things? I’m with Ishmael all the way on the Pequod. There is a “damp, drizzly November” within me, that it’s “high time to get to sea as soon as I can.” I honestly don’t think I write / read to stave off ennui, malaise, but maybe there is something there. Maybe it works that way on a much more unconscious level than Ishmael’s. I love his feelings, his sentiment. I have a confession: maybe I am, in my heart, a Romantic? I want the same things Ishmael wants. The search for the whale is different for Ishmael than it is for Ahab. I have no whale. As for the speaker’s journey(s) in Ishmael Mask—he’s simply a wanderer as well; he’s looking with no clear purpose, no ultimate direction in mind. Maybe running and leaving and hiding a bit.

WJH: Ishmael Mask contains a number of poems that seem to mock their speaker. In “Queequeg Mask,” the speaker carves a coffin and then lies inside, as did Moby-Dick’s Queequeg. The poem’s concluding lines quote Melville directly: “if a man made up his mind to live,/ mere sickness could not kill him.” A speaker’s hubris appears again in “Memnon Stone, Terror Stone.” Here, the character Pierre has challenged a stone to fall on and kill him and, when it doesn’t, he stands “haughtily on his feet,/as he owed thanks to none, and went/on his moody way.” In a final example, the speaker seems to mock himself as he dreams of a “wine-dark” sea; he, the heroic Odysseus, his prison cell, a ship. Can you explain whether these poems are meant to be read ironically? And, if so, how do they function in the collection?

CK: Initially I thought Ishmael Mask to be much more insouciant, playful, funnier than Cage. Some folks have said this is not really so. I thought the speakers in these poems, though serious at times, were also winking and giggling. There is a self-mockery when I find I’m taking myself too seriously. It’s serious but it’s also a joke. I love gallows’ humor, the most inappropriate joking, etc. The darkest places are the funniest, the silliest, where the most absurd things happen. I mean, for me, the very act of writing a poem is absurd. It’s complete hubris—“I have something to say, etc.” There are so many poems, so much art in the world, to think that I dare add to that—ha. There must be this acknowledgment of hubris, too, in a way. That one must think on the complete flip side, that one does have something new to say, that yes…I can add to this history. Even though it will all be forgotten in the near future. It’s the absurdity of creation that I find so lovely and intriguing. The complete dedication, the belief in oneself, the complete commitment to something that will soon be washed out to sea. I love it! So, there’s irony, there’s absurdity; dark humor, laughter; however, my absurdity is also my seriousness, that is, this is generally how I feel, think, believe.

WJH: Cage of Lit Glass, Pierre Mask, and Ishmael Mask are all image-rich, and no image in them is more intriguing to me than that of floating. In Cage’s “Bodybuilder,” the speaker says: “I can become something else./Take my eyes outside, let them float/overhead.” The opening lines of the third section’s “The Lost Boy,” begin: “Headless statues float in a broken/open Cornell box…”

In Ishmael Mask, the floating seems to have taken on an entirely different quality. In “Ohio”, it seems whimsical: “Later, we huddle in// the flooded basement, watching//the washing machine float by./We call it a chapel.” And though the poem “Frames,” will reach a darker conclusion, its initial buoyancy seems almost magical: “For the moment we are floating/out on one of the black/islands you describe so clearly, serene,/comfort, you say…” Do you think this change describes a shift in the speaker’s orientation?

CK: I was five years old, in my parents’ house, walking back to my room over brown carpet when I suddenly realized, huh, this life is all there is, there is nothing else. I didn’t feel sad, glad, or really anything at all at this moment. Who knows? Maybe I’m wrong? But my whole life I’ve felt like I’ve been floating along, that I’m both here and not really here. I then try to stay in the moment, be as present as I possibly can, and that works a little. But when I’m reading, writing I feel as if it’s not really happening. Sitting in a jail / prison cell back in 2006 / 2007, sitting in rehab, or even visiting a loved one in hospital—things that seem “really real” were strange, as though I were floating along the whole time. I’m not making sense, I know. Carrie and I just returned from hiking in Vermont. It was such an amazing time. I’m walking up this mountain, stepping on rocks, but it’s still as though part of me is not there. I am so tickled you pointed those moments out to me. I’m thinking now, damn, I should have edited some of the “floating stuff” but it’s how I’ve always felt and I can’t get outside of it. Ishmael is a floating character; Pierre is a character who floats. Bartleby is a cloud. All of Kafka’s characters are individuals who float. Beckett’s characters are floating voices.

WJH: Both of your collections, toward their conclusions, include a poem set in what might be considered an Elysium. The first, “Tower of Birds” is takes place in a garden with swans circling, beetles sleeping, and a speaker who is “made of earth, cool /moss” covering his feet. The second setting is wilder: a field somewhere in Kansas where water is absent, but hoped for and a missing person is sought. In both poems, the speaker is accompanied, and I wonder if you might talk about the difference between the speaker’s companions in poems which conclude very differently.

CK: I spend a good deal of time alone. I love being alone and crave solitude. Many of my poems feature lone speakers in lonely environments. On the flip side, I love people. People are so beguiling, frustrating, strange, horrible, cruel and also caring, compassionate; people are simultaneously boring yet wildly unpredictable; people are just so damn weird—I’m stating the obvious here. Often, I think, the poet is all Id, all animal and wild, complete monomaniacal (like Ahab!), me me me, the “I,” etc., whereas the novelist is more Ego, more concerned, ultimately, with the lives of people. I don’t really believe this and think it much more diffuse, complicated than my bad dichotomy. I know poets who care much more about the world of people than some novelists. A fiction writer I love, David Markson, often has solitary speakers in his later work. So, I can poke holes in that thought…. “Tower of Birds” is a love poem for Carrie. Timothy Liu challenged me—years ago—to write a love poem and that was it. Carrie is really the only person I spend a lot of time with. We can hang out and talk seriously, be silly, and also not talk at all— we can both do our own things. That poem is set in the Toledo Botanical Garden, a place we used to visit often. Carrie has saved me in too many ways to relate. “Amerika” is a different type of love poem; Kafka, I feel, has been there for me for such a long time, a lot of times when others have not. That’s a wandering, searching, “road” poem. Try to find Kafka, but he’s here all along in the books. I’m thinking of Kafka’s Amerika, or The Man Who Disappeared (1927), Karl Rossman, who gets exiled to America and ends up working in a circus in Oklahoma. I’m also thinking of Martin Kippenberger’s glorious installation, The Happy End of Franz Kafka’s Amerika (1994). Before I went to college—I didn’t go to college right away—I worked in a factory for a number of years, there were these names that seemed to float in the air—Kafka, Dostoevsky, Chekhov—and I went to the library and grabbed these books and devoured them. Kafka was always there and not there, too. I spend a part of each day thinking about Kafka; I often quote another favorite writer, László Krasznahorkai: “When I am not reading Kafka I am thinking about Kafka. When I am not thinking about Kafka I miss thinking about him. Having missed thinking about him for a while, I take him out and read him again. That’s how it works.” Kafka is, though, “the man who disappeared,” and that poem is the search. I always thought and argued that all of my “companion” poems are love poems.

WJH: The speaker of Ishmael Mask yearns for connection, and the act of writing seems to be a primary vehicle. In “Perfume,” the initials carved in a tree are “…love letters we scrawling on cedar…”

The speaker in the poem “Carrie” is anchored by sketched images: “For thirteen years/I’ve floated in the atmosphere//ready to burst, the brown strands/of your hair keeping me there.//All this time I’ve been drawing you.” You have said that there is no more optimistic act than writing a poem. Are the references to writing and drawing which are prevalent in this collection evidence of that?

CK: I believe in my bones that there is no more optimistic act than writing a poem, drawing a picture, playing music, practicing and creating any type of art. Writing is everything; every text, to me, is a letter of some sort, an epistle. I’ve written letters all my life, and still do, albeit less frequently. I wonder, often, are prisoners the last letter writers? The very act, the time, the commitment it takes to piece and stitch a manuscript together, it’s such an act of love, of devotion and optimism; also, no book is ever made in a vacuum, books are always acts of collaboration. Now, one might have 5-10 readers (way too many, in my opinion—but whatever works), or one might have a single reader, one person who helps. Cage was written intensely and with Peter Covino and Timothy Liu, with great help from them, and also with Christine Stroud, my wonderful editor at Autumn House Press. With Ishmael, I wanted to do something different; this book is Miguel Murphy’s book; he was really the only person other than Christine, who closely helped out. I was visiting my mother last August (2022), and Miguel would talk to me for hours on the phone, editing, reordering, cutting and revising. I listened to every damn word, mostly. Working on these books with these people are such acts of trust and love. These things are profoundly optimistic. All the poems are love letters, in many ways, each poem can be viewed as an ars poetica; they’re poems about poems, art, literature.

WJH: How, if at all, does your teaching as an assistant professor of English at The Community College of Rhode Island, as well as your work as editor of The Ocean State Review, nourish your life as a poet?

CK: The best part of working on the Ocean State Review is talking with other poets, writers, artists. I’ve made friends through this journal. I love discovering new poets and new work. Talking poetry, writing. When I took over the journal in 2015, the first poets I contacted for work were Michael Palmer and Medbh McGuckian—and they responded, with poems! I opened the 2016 issue with poems by Keith Waldrop and Rosmarie Waldrop. I also like to place poems, essays by writers who have never published before. I always joke about working on journals and presses: the hours are forever and the pay is nothing. Working on a journal or press is such a labor of love. In a completely different way I feel teaching informs. Not so much discovering new work but being around people. It’s always wonderful when a student gets excited by a poem, a story.

WJH: Thank you so much, Charles, for taking the time to speak with me!

_____________________________________________________________

Charles Kell is the author of Ishmael Mask, (Autumn House Press, 2023.) His first collection, Cage of Lit Glass, (Autumn House Press, 2019) was chosen by Kimiko Hahn for the 2018 Autumn House Press Poetry Prize. He is an assistant professor at the Community College of Rhode Island and editor of the Ocean State Review.

https://www.autumnhouse.org/books/ishmael-mask/

W.J. Herbert’s debut collection, Dear Specimen (Beacon Press, 2021,) was selected by Kwame Dawes as a winner of the 2020 National Poetry Series and awarded the 2022 Maine Literary Award for Poetry. Her work, awarded the 2022 Arts & Letters/Rumi Award for Poetry, also appears, or is forthcoming, in The Atlantic, Best American Poetry, The Georgia Review, The Hudson Review, The Southern Review, and elsewhere.

https://wjherbertpoet.com/

https://www.autumnhouse.org/books/ishmael-mask/

W.J. Herbert’s debut collection, Dear Specimen (Beacon Press, 2021,) was selected by Kwame Dawes as a winner of the 2020 National Poetry Series and awarded the 2022 Maine Literary Award for Poetry. Her work, awarded the 2022 Arts & Letters/Rumi Award for Poetry, also appears, or is forthcoming, in The Atlantic, Best American Poetry, The Georgia Review, The Hudson Review, The Southern Review, and elsewhere.

https://wjherbertpoet.com/