SoFloPoJo Contents: Home * Essays * Interviews * Reviews * Special * Video * Visual Arts * Archives * Calendar * Masthead * SUBMIT * Tip Jar

November 2023

Reviews of: Quiet Armor by Stevie Edwards, & To See What Rises by Alison Stone

Reviews of: Quiet Armor by Stevie Edwards, & To See What Rises by Alison Stone

Expectations and shaming of the body. Rape and assault. Alcohol and loneliness. Depression and suicidal ideation. Chronic pain and political turmoil. Desire and joy and doubt and desire. In Quiet Armor, Stevie Edwards takes the reader on a journey to explore the myriad ways in which violence and loss of agency are centered on women’s bodies and how the body is and can be a vehicle for connection or pleasure.

The first section of the book explores the impact of family and early experiences on the ability to love the self. In “Ladylike,” the father scolds a very young girl for not wearing a shirt in the heat of summer, and later in the poem, after the speaker gets her period at 11, her mother chastises her, tells her it came early because she is too heavy, and “I tell her I’m sorry/because I never know what else to say/for being fat, for not being a boy, for bleeding.” In “Body,” window shopping for a wedding dress, the speaker remembers her mother’s tiny-sized wedding gown, the chiding expectations about her own body type, thinks, “These were the years I was too full to be useful.” There is an unraveling of family history that reveals the mother’s difficult past and a wobbly sort of truce between an ill mother and a daughter who has made a suicide attempt.

But there also is an honest portrayal of the questionable decisions we all make in the alter-ego narrative of “Nobody,” and a commentary on masculinity and grief in “Essay on Guns,” where a teenage boy is killed by a found gun, “the grief/of a father a little like a bullet wound—/so much pain gushing out the body/it stains the whole world red.” This segues into poems about violence against women, in history, mythology and the modern world. In “Red Spell, a tour de force poem toward the end of the first section, Edwards opens with the poinsettias decorating the church of her young mother’s wedding and uses that as a springboard for a brilliant poem about abortion rights:

Call me red hoarder.

Red lover.

Red arbiter,

piggish red

rover bungling the almost-lives of ovum.

For centuries women used the red of poinsettias to expel a wrong red.

(When I say expel, I mean abort.)

[...]

Red-faced men arguing

(again) whether Penny should rusty-knife red

dirty-dancing die on a red-soaked folding table.

What to do when the men want to say yes (again).

When all we have left is red.

And in the last poem of the first section, Edwards' “Self-Portrait as Medusa,” the fantasy of power over men has the speaker turning an abuser from her youth into stone and prominently displaying him on the front lawn.

This signals a turn toward the second section containing a sequence of poems, beginning with “Drunk Bitch Dreams of a Luminous Stream,” that explore sexual encounters, some fueled by alcohol, all highlighting the search for contact and intimacy. This section also makes use of historical and mythological women to show that violence against women’s bodies is a legacy. In addition to Medusa, we have Saint Agatha, whose breasts were cut off, Lavinia of Titus Andronicus, whose hands and tongue were cut out, and Persephone, kidnapped and held against her will. In another brilliant mix of the old and the current, “Saint Christina” blends the testimony of Christine Blase Ford in the Kavanaugh confirmation hearings with the suffering of the Catholic Saint Christina, often called Christina the Astonishing, who was tortured in numerous ways and rescued by angels:

To be astonishing

might be the only rational act

for a woman. To throw

your body into a furnace,

a mill wheel, the paparazzi

& see if it’s true, God

has blessed you.

The book has many tender moments, which first show themselves in the company of other women. In “Dream Without Men,” the speaker details a love that is gentle and more than physical, one where “we are as naked & safe as we’ll ever be. The way I love her/is & is not sexual. The way I love her is older than each of us.” In “Some Things We Carried,” Edwards provides a litany of bonding images that women will instantly recognize:

Sometimes we carried keys to buildings we didn’t live in anymore. Sometimes we carried mace & feared it would be used against us. [...] We carried each other’s pregnancy tests & Plan B & Monistat & in CVS bags hidden beneath things we didn’t really need: extra toothbrushes, deodorant, iced tea. We carried the names of children we feared having. We carried tampons & Xanax & books of poems. We carried our youths.

The third section shows the discovery of how beautiful and difficult it is to trust real intimacy when the world and your own body seem to conspire against you. Chronic illness and depression still abide with the speaker here, in poems like “Some Threads from a Depression” and “All the Heavens Were a Bell.” The loss of desire from medication in “On Want”:

These days lust won’t speak to me.

Buried in drugs that keep me less angry at

it’s hard to say exactly what. I want so badly

to want again.

But there is also a new relationship here, one that treasures the lover’s “healed ribs and questionable tribal tattoo.” One where a “chorus of rescue dogs” can “teach me the trick to eagerness.” In a poem addressed to extra-terrestrials, the impossible task of explaining human desire: “I can’t explain why we keep doing it:/pull a body into a body & say this/is the best we can do as humans./But it’s true. It’s true every time.” There is a self-awareness of the difficulty of finding this kind of love in the world and rejoicing in it, in “Epithalmion:”

Love, here is my hand, my gallons of blood

that choose to keep rushing me into

today. I almost missed this: your breath

steaming my neck. I’ll take it. I do. I do.

And, in the last poem, “Tapping Therapy,” Edwards acknowledges the difficulty of moving through the inhospitable world and ends the book with the admonition to “let the old stories close.”

This exploration of the quiet armor that women wear as they go to war— whether against family expectations, societal norms, political intrusion, abusive men, self-loathing, mental illness, addiction, or sickness—both sings and haunts. It questions the quiet of this armor. It shakes its metal plates, making a fierce and undeniable noise.

Donna Vorreyer is the author of To Everything There Is (2020), Every Love Story is an Apocalypse Story (2016) and A House of Many Windows (2013), all from Sundress Publications. She hosts the online reading series A Hundred Pitchers of Honey.

What do you get when you read Alison Stone? The experience of poetry is exposure to some of the following: a self, a set of references, a poetics, and a politics. She is the goddess of the ghazal, the living, witty zombie-prophet who brings the light of the mind to many a darkness.

To See What Rises is Stone’s tenth book of poetry. She has also published: They Sing at Midnight (2003), From the Fool to the World (2012), Borrowed Logic (2014), Dangerous Enough (2016), Ordinary Magic (2016), Dazzle (2017), Masterplan (with Eric Greinke, 2019), Caught in the Myth (2019) and Zombies at the Disco (2020). Every page I’ve read so far has been good.

The back cover of her books and her poems tell us that she is a survivor of family pain and some relationship crash-landings, that she was THERE with punk rock, that there might have been some heroin involved (or was this about a client, or pure fantasy?), and that she loves her daughter. From LinkedIn we learn that she is a Gestalt therapist who helps creative people (. She also throws a mean tarot. More than that—she has made her own tarot deck. She can handle popular culture with great gravitas. Also playing in her orchestra are the communal spirit of Judaism, a fearless feminism that makes the knowing of vulnerability and memory into a superpower, and a spirit of rebellion that is never naïve about the cost of displeasing City Hall or about the benefit of craft. (One early reviewer claimed that she is a non-literary writer, but I have no idea why.)

What does she write about? In addition to previously mentioned interests, she casts a mean poetic spell against Donald Trump and the moral nihilism that surrounds, say, shootings in America. Consider a most recent poem, “Travesty,” about Zimmerman shooting Martin:

Skittles, iced tea, unarmed. Seventeen years

old. Looks like he’s up to no good…he’s just star-

ing at me. Though cops tell Zimmerman to stay

in his truck, he gets out to find a stre-

et sign. Fox News anchors rave

bout gold teeth, suspension, drugs. Show Trayv-

—the words are broken in places where they are not supposed to be broken, e.g., between syllables or double letters. What do we do with outrageous situations, with shards of what should be? One thing we can do is not shut up. We can speak. The poem is not meant to shame the Devil—impossible, these days. It is a song to unify the witnesses, to share reality when reality is under attack.

Her poems recount desire and outrage. Poetic outrage and assertions of dignity in the face of humiliation are sung in the key of clarity: there are no Dadaesque poems in her collections. She does not sacrifice logic to make her words dazzle. She thinks a lot about logic, actually. Her 1988 poem “Not Seeking New Worlds” is a poem about the coldness of daddy that shows Stone to be a true daughter of Sylvia Plath:

It wasn’t the pointed ears, it was the box

Of feelings locked and hidden that made

Spock my father’s idol. I preferred the Captain.

Emotions didn’t seem

To hurt him as he steered the ship

Through meteors and Klingon raids.

The robotic distance from emotionality—which characterizes the original Star Trek, though not that show’s reincarnations—exacts a toll on the daughter:

Feelings were the enemy, green

With five arms and a laser gun. I was trained

To laugh softly, if at all,

And never to cry. Computers

Don’t even have to eat.

This hint of anorexia is followed by a darker result, almost a version of Lou Reed’s “Perfect Day”:

On heroin, pure reason’s almost

Possible. I don’t

Raise my voice as Dad says yet again

That homosexuals are sick and Art’s

Unnecessary now that we have cameras.

For another fine thinking-through-popular-culture poem in this volume, go to “All in the Family,” which looks back to a time when we imagined the red and the blue mixing in the same living room.

Stone is an exquisite practitioner of the mythical method. She has entitled one of her books Caught in the Myth, and I wonder if she doesn’t have the best Persephone poems in English. We all know the story—a young girl is kidnapped into the underworld and, poor dear, she eats some pomegranate seeds, and so it is adjudicated by powers-that-be that she must spend half of her (?) annual existence under the earth. It’s so unfair, just like winter in Massachusetts (where Stone was born). The mythic origin story of the seasons is poetically refigured into the disappointment inherent in sexual desire, which Stone recasts in “Borrowed Logic”:

Mother warned, Sex is a trap.

Still, every teenager wants more

Than flowers, more than stale, virginal green.

His lips, cool moss against my nape.

I traded sunlight for a romp

In the forbidden, a devoted mate.

The excitement of eros is channeled into the present moment, and the mother’s warning is a condition of existence for every woman: you will be told to live in fear of your desire. Where do things get tricky? Stone rides the wave of troubled desire until she gets to the word “devoted”—that’s when we know things are going to break. Poor Persephone—the condition of impermanence is such that you do not get stability through time. Not an option. It’s not a long poem after that. Here’s where it goes:

My meadow-scent’s exotic here, so he’s eager

to please, writes me poems by the meagre

glow of dying fireflies. If he’d only kick that mange-

infested dog out of our bed. Such horrid pant-

ing! Each tongue licks my face like meat.

The words broken in the wrong place are the intersection of two moments: before and during the awareness of disappointment. The image of a few pomegranate seeds or a mange-/infested dog is the short-hand or mirror shot of what we cannot see directly even when we know it is coming: heartbreak.

To See What Rises is rich with enchanting intersections. “But Not His Name” braids life during the COVID-19 epidemic, Stone’s outrage about the shooting of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman, and the long shadow of American racism. The scene is set with mention of COVID—we have “Returned to work” and “we sweat into our masks”—but then we encounter

I AM NOT A RACIST, the racist yells

while bodies pile up like bags of gold.

How do we make poetry out of everyday horror? We remember the refrigerator trucks in New York City when the hospitals were simply overwhelmed, and in the poem’s poetic montage we pass through these deaths to the racist protestor image, which gives way to the memory of the poet’s grandfather:

It’s always about who has the power.

Years ago, at Ellis Island,

my grandfather, but not his name, allowed

to enter. Boats of Jews turned back to die.

What does it mean

to be American?

Are the protesters yelling about Antony Fauci, or are they supporters of Zimmerman? The poem ends with this image, a juxtaposition of Zimmerman with a Fourth of July display in a neighbor’s yard:

Zimmerman autographs Skittles.

Fake stallions watch through moss-covered eyes.

“The horror, the horror,” as Conrad’s Kurtz says in Heart of Darkness. A poem that recounts outrage and disgust alone will not suffice as a poem, though, as every poem is a kind of shrine. The recurrences and comparisons we find throughout As It Rises are the value preserved through articulate images and careful line-breaks.

The cycles of desire, destruction, and renewal in these poems are beautiful to watch. In “After the Break-Up Sex and Broken Glass,” Stone comments on this rise and fall and rising again after the fact:

I wander through a field of asphodel

Whose white spikes whisper,

All desires wan. Thrills fizzle.

The trick’s to live diminished

without bitterness. Sleep,

wake, work to outwit bills that spill red ink

across your fantasies. Let your

ringless fingers reach. Kiss

when you can. Find a song that still

spurs you to dance. Every five years

burn your self in effigy

to see what rises from the ash.

The title of a beautiful book of poems rises from the ash, among all the quotidian details and the remarkable practice of burning one’s self and (not oneself). May we all have this when we write.

John Whalen-Bridge is the author of Political Fiction and the American Self (1998) and Tibet on Fire: Buddhism, Rhetoric, and Self-Immolation (Palgrave, 2015.,) “Buddhism and the Beats” appeared in The Cambridge Companion to the Beats (2017). He is currently working on a book about engaged Buddhism and postwar American writers, as well as literary biography of Maxine Hong Kingston. Together with Maxine Hong and Earll Kingston, Joe Lamb, David Johnson, Joanne Palamountain, and Katherine Taylor, he performed selections of Lincoln in the Bardo for the 2018 American Literature Association, which was fun.

August 2023

The Plague Doctor, The Halo of Bees, The Naming of Things

by James C. Moorehead, Michael Hettich, Gary Light

The Plague Doctor, The Halo of Bees, The Naming of Things

by James C. Moorehead, Michael Hettich, Gary Light

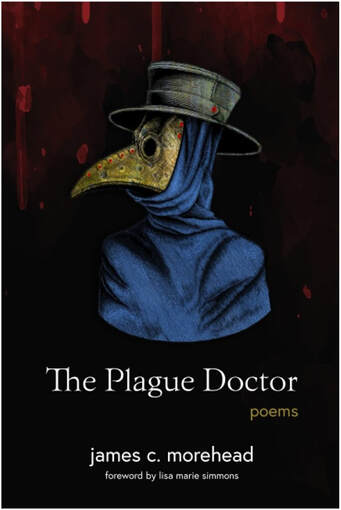

The Plague Doctor: poems,

by James C. Morehead

ISBN: 978-1-7367890-5-6

Viewless Wings Press: 2023

Review by Carmine Di Biase

I have been following James Morehead’s poetry since his first collection, canvas: poems, which appeared in 2021 and was followed the next year by portraits of red and gray: memoir poems. Now we have The Plague Doctor, a collection of twenty-seven poems, all of them remarkable for their variety and technical dexterity. Morehead embraces formal conventions—the sonnet, for example, or rhyme in general—when they suit his material; but he is entirely, and perhaps most, at home with free verse. The strength of this new, engrossing collection lies in Morehead’s authenticity of feeling and the coherence of his poetic vision. These poems, despite their kaleidoscopic variety of form, communicate with one another through a deeply felt, carefully developed unifying theme: time, its deadly hold over us, and the refuge that is art.

To Morehead, however, if art is to serve as a refuge it must include an element of play, as is suggested by the first, and titular, poem, “The Plague Doctor.” In Renaissance Europe, the plague doctor was often not a physician at all but a kind of poseur, whose real job was to count the infected and the dead. The doctor’s iconic mask, with its long beak, was stuffed with aromatic flowers and herbs that were thought to filter out the plague. “It is the mask I can’t shake,” says the voice of this poem, in reference to “a photo” someone “shared” on Halloween. Natalia Andrus, on the facing page, responds to this poem with a striking ink drawing, one of three which she contributes to this book (complementing most of these poems are images by other artists and photographs by James Morehead himself). The image of the plague doctor is morbid, to be sure, but Halloween—like the Venetian carnival, where the plague doctor’s mask is among the most recognizable costumes—is playtime, albeit a dreadfully serious kind of playtime. It is, literally, a way to play games with time and thereby, however temporarily, to defy it.

That Morehead has arranged his collection in three sections called “acts,” each one containing nine poems, urges us in fact to see it as a play, a performance of sorts. Among the most affecting poems in Act I is “Ghosts of Bodie, California,” which paints an arresting still-life of the abandoned gold rush town:

They floated beside me on unpaved streets,

among the headstones gathered on a hill,

past rusted carcasses of mining gear,

a “De Luxe Ford” stripped, half sunk--

the church, town bank, and

outhouses scattered there, and here.

This poem’s imagery, captured also in two photographs on the facing page, is housed in appropriately spare free-verse lines, and Morehead’s sensitive control of rhythm is everywhere evident, as it is toward the halting conclusion: “time decays,” says the speaker, and “one by one the settlers fled, / until the last home’s lights went dim.”

Time, which has reduced this town to skeletal remains, seems mocked by the last poem in Act I, the subject of which is an artist who draws the skeleton of a French bulldog, then also that of the speaker. Skeletons, says the artist, “are serene,” but like all skeletons, this dog’s has a “laughing skull.” (This unsettling image comes to life, as it were, on the facing page, in a drawing by Natalia Andrus). The speaker, posing for the artist, is also unsettled, “left motionless in the dark, / waiting for tomorrow, and tomorrow.” These concluding words ask us to mull over Macbeth’s grim response to the sound of his wife’s dying scream. “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow,” he says, life “creeps” along with its “petty pace” until—and this is significant to Morehead’s vision—“the last syllable of recorded time.” Time is measured out, “recorded”—mocked even—by the syllables we speak, the best of which amount to poetry.

In Act II, where nearly everything is in lower case, art and life become one. In a poem called “where canvas ends and bush begins,” nature’s “watercolor strokes blend sky into spring,” and “mother earth” makes her colors “crisply waltz at autumn’s peak.” In another poem in this section, the speaker is in a gallery, looking at paintings with a companion who minimizes the marvel of them as a result of “technique.” Vicariously, however, the speaker sinks helplessly into painting after painting—into “a whirlpool,” for example, “of rainbow hues / entwined into tendril fingers / and a sailboat sliding through azure foam”—and, detached from the conversation, has the final, private words: “i close my eyes and walk away.” The title of this poem, “is the image already there,” gets to the heart of the artist’s work as the selfless revealer of nature’s art, the lifter of the veil that covers nature’s timeless images.

Here and there, throughout this collection, there are subtle references to computers. The image in “The Plague Doctor” is, again, “shared,” which could mean it was sent electronically. Morehead’s poems, in short, are of our time, a point that is driven home by the surreal concluding poem: “When you perform my autopsy, be prepared.” The surgeon will find “eyes made of glass” that can “perform the perfect wink,” and no blood but “oil for hydraulic muscles.” The speaker’s “memory” is nothing but “quantum sparks,” which will fire only until “fusion’s chain reaction ends.” The anxiety, and the wryness, of the voice of this poem are our own. “I’m a Potemkin village of a man,” he says, “an illusion.” That, “perhaps,” is why he has “forgotten how to sleep” and stares “unblinking into darkness,” his “mind racing at the speed of light, / trying to solve the world’s problems / queued up to infinity.” On the facing page is Andrus’s third, arresting drawing: a man’s head, his skin partially removed to reveal the gears and wires beneath, and a skeletal, mocking grin. This playfulness, and specifically this mocking, aping quality, which is rooted in self-awareness, is what animates these poems; it is what makes us human.

There is a good reason why Morehead has been appointed for a second term this year as poet laureate of Dublin, California. He has been working tirelessly on Viewless Wings: a rich online resource which publishes the work of numerous poets and interviews with them, both in the form of audio files and transcriptions of them. And this he does in addition to all the public readings which he participates in or organizes. This work has enriched his community of poets and readers, but it has also allowed him to deepen and refine his own writing. The Plague Doctor, a collection which fruits new meanings with every rereading, is Morehead’s best work so far.

by James C. Morehead

ISBN: 978-1-7367890-5-6

Viewless Wings Press: 2023

Review by Carmine Di Biase

I have been following James Morehead’s poetry since his first collection, canvas: poems, which appeared in 2021 and was followed the next year by portraits of red and gray: memoir poems. Now we have The Plague Doctor, a collection of twenty-seven poems, all of them remarkable for their variety and technical dexterity. Morehead embraces formal conventions—the sonnet, for example, or rhyme in general—when they suit his material; but he is entirely, and perhaps most, at home with free verse. The strength of this new, engrossing collection lies in Morehead’s authenticity of feeling and the coherence of his poetic vision. These poems, despite their kaleidoscopic variety of form, communicate with one another through a deeply felt, carefully developed unifying theme: time, its deadly hold over us, and the refuge that is art.

To Morehead, however, if art is to serve as a refuge it must include an element of play, as is suggested by the first, and titular, poem, “The Plague Doctor.” In Renaissance Europe, the plague doctor was often not a physician at all but a kind of poseur, whose real job was to count the infected and the dead. The doctor’s iconic mask, with its long beak, was stuffed with aromatic flowers and herbs that were thought to filter out the plague. “It is the mask I can’t shake,” says the voice of this poem, in reference to “a photo” someone “shared” on Halloween. Natalia Andrus, on the facing page, responds to this poem with a striking ink drawing, one of three which she contributes to this book (complementing most of these poems are images by other artists and photographs by James Morehead himself). The image of the plague doctor is morbid, to be sure, but Halloween—like the Venetian carnival, where the plague doctor’s mask is among the most recognizable costumes—is playtime, albeit a dreadfully serious kind of playtime. It is, literally, a way to play games with time and thereby, however temporarily, to defy it.

That Morehead has arranged his collection in three sections called “acts,” each one containing nine poems, urges us in fact to see it as a play, a performance of sorts. Among the most affecting poems in Act I is “Ghosts of Bodie, California,” which paints an arresting still-life of the abandoned gold rush town:

They floated beside me on unpaved streets,

among the headstones gathered on a hill,

past rusted carcasses of mining gear,

a “De Luxe Ford” stripped, half sunk--

the church, town bank, and

outhouses scattered there, and here.

This poem’s imagery, captured also in two photographs on the facing page, is housed in appropriately spare free-verse lines, and Morehead’s sensitive control of rhythm is everywhere evident, as it is toward the halting conclusion: “time decays,” says the speaker, and “one by one the settlers fled, / until the last home’s lights went dim.”

Time, which has reduced this town to skeletal remains, seems mocked by the last poem in Act I, the subject of which is an artist who draws the skeleton of a French bulldog, then also that of the speaker. Skeletons, says the artist, “are serene,” but like all skeletons, this dog’s has a “laughing skull.” (This unsettling image comes to life, as it were, on the facing page, in a drawing by Natalia Andrus). The speaker, posing for the artist, is also unsettled, “left motionless in the dark, / waiting for tomorrow, and tomorrow.” These concluding words ask us to mull over Macbeth’s grim response to the sound of his wife’s dying scream. “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow,” he says, life “creeps” along with its “petty pace” until—and this is significant to Morehead’s vision—“the last syllable of recorded time.” Time is measured out, “recorded”—mocked even—by the syllables we speak, the best of which amount to poetry.

In Act II, where nearly everything is in lower case, art and life become one. In a poem called “where canvas ends and bush begins,” nature’s “watercolor strokes blend sky into spring,” and “mother earth” makes her colors “crisply waltz at autumn’s peak.” In another poem in this section, the speaker is in a gallery, looking at paintings with a companion who minimizes the marvel of them as a result of “technique.” Vicariously, however, the speaker sinks helplessly into painting after painting—into “a whirlpool,” for example, “of rainbow hues / entwined into tendril fingers / and a sailboat sliding through azure foam”—and, detached from the conversation, has the final, private words: “i close my eyes and walk away.” The title of this poem, “is the image already there,” gets to the heart of the artist’s work as the selfless revealer of nature’s art, the lifter of the veil that covers nature’s timeless images.

Here and there, throughout this collection, there are subtle references to computers. The image in “The Plague Doctor” is, again, “shared,” which could mean it was sent electronically. Morehead’s poems, in short, are of our time, a point that is driven home by the surreal concluding poem: “When you perform my autopsy, be prepared.” The surgeon will find “eyes made of glass” that can “perform the perfect wink,” and no blood but “oil for hydraulic muscles.” The speaker’s “memory” is nothing but “quantum sparks,” which will fire only until “fusion’s chain reaction ends.” The anxiety, and the wryness, of the voice of this poem are our own. “I’m a Potemkin village of a man,” he says, “an illusion.” That, “perhaps,” is why he has “forgotten how to sleep” and stares “unblinking into darkness,” his “mind racing at the speed of light, / trying to solve the world’s problems / queued up to infinity.” On the facing page is Andrus’s third, arresting drawing: a man’s head, his skin partially removed to reveal the gears and wires beneath, and a skeletal, mocking grin. This playfulness, and specifically this mocking, aping quality, which is rooted in self-awareness, is what animates these poems; it is what makes us human.

There is a good reason why Morehead has been appointed for a second term this year as poet laureate of Dublin, California. He has been working tirelessly on Viewless Wings: a rich online resource which publishes the work of numerous poets and interviews with them, both in the form of audio files and transcriptions of them. And this he does in addition to all the public readings which he participates in or organizes. This work has enriched his community of poets and readers, but it has also allowed him to deepen and refine his own writing. The Plague Doctor, a collection which fruits new meanings with every rereading, is Morehead’s best work so far.

Carmine Di Biase’s chapbook, American Rondeau, was published by Finishing Line Press in 2022, and his poems have appeared in various journals, including Italian Americana, South Florida Poetry Journal, Scapegoat Review, and The Vincent Brothers Review. He writes about Italian and English literature, often about Shakespeare. His articles and translations appear in academic journals and also, on occasion, in the Times Literary Supplement. His translation of Carlo Collodi’s sequel to Pinocchio will appear this fall, in a bilingual, newly illustrated edition. He is Distinguished Professor of English Emeritus at Jacksonville State University in Alabama.

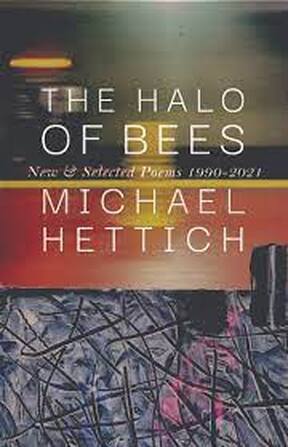

The Halo of Bees: New & Selected Poems 1990-2022

Michael Hettich

Press 53 2023

By Kurt Luchs

One of the first things you notice about Michael Hettich’s poems is that they cannot easily be summarized or described. I mean that as a compliment. They are completely themselves.

These verses have been so lovingly labored over it is difficult to notice the work that went into them, we feel them come alive and fly. I am reminded of something I learned from The Variorum Edition of the Poems of W. B. Yeats. The poet would often revise his work by removing or toning down the images or phrases in individual lines in order to make the poem stronger. In Hettich’s work, we get the sense of infinite possibility, of how things might very well have been different. And then suddenly, in the next line or the next stanza, they are different, as in the last stanza of “The Dark House”:

or moving through the dark like the moon does, pulling

the tides inside us, oceans we might even

swim out in, naked and warm, until morning

when we’ll be out of sight, so far from shore

our lives might go on without us.

This generous selected poems pulls from all except the first of Hettich’s twelve full-length collections, and all but the first two of his many chapbooks. Reading this marvelous body of work in one go has made me curious as to what was left out. I tried to satisfy my curiosity by ordering what was apparently the last extant copy of his first collection, Lathe, and am eagerly waiting for it.

This new and selected volume opens with a batch of new poems called “The Shape of Moving,” perhaps influenced by his retirement from a lifetime of teaching and subsequent relocation from Florida to Black Mountain, North Carolina. No matter what sparks a Hettich poem, it opens a dimensional door to an inner place where thoughts, feelings, memories, dreams and visions intermingle in surprising, unpredictable ways leaving the the reader transformed. This is a poetry of illumination and transcendence grounded in the things of the earth. In “The River,” Hettich opens the piece like this:

I’m taking a pause from the person I’ve been

for most of my life and starting to enter

the man I’ve been only occasionally, even

the man I’ve only pretended to be--

a stranger I’ve hardly imagined.

It turns out his wife—a frequent presence throughout his work—is undergoing the same mysterious change. They agree to do it together, whatever it is. The middle of the poem offers some clues:

The river that runs by our house has been rising

for weeks. We’ve been cleaning out our closets,

tossing things into the swirl:

old books we thought we should love, classics

that only bored us, as they’ve bored everyone

for centuries […]

And then comes a typical Hettich ending, if there is such a thing, an ending that is really more of a beginning based on a new consciousness, a new awareness:

Even our faces in the mirror seem

to have been swept away now by that rising river

and by our yearning. I can only be naked,

though I’m trying to locate the clothes I wore

when I was a man who sported perfect teeth

and a full head of hair, the kind who tells the truth

when he lies—or vice versa, I can’t remember now,

though I’m sure it must matter to someone.

I want to single out some of the poems in this book that struck me most strongly. From the opening of “The Stone Wall,” one of the new poems:

I am coming to the end of something, I can feel it

like a bone that was useful in the past, that kept me

standing upright but has turned into a toothpick

or a splinter dissolving in my blood […]

Here are some lines from the middle of “The Bullfrogs,” about his initial experiences in the Everglades with his wife after moving to Florida. First he tells us “every time / we pulled off the road there, we had to take off / our clothes for a swim in the black water […]. Then:

We marveled at the fact that so few people

came out here to swim: The water smelled like flowers.

For that whole first year we had no idea

those croaks we found so charming were actually

challenges from bull alligators establishing their territory,

calling anything in the immediate vicinity

to make love or fight, and they were hungry too.

This is a very representative a Hettich poem in several ways. First of all, for its candor and his willingness to tell self-deprecating tales. Secondly for his immersion in the natural world, both literally and figuratively, motivated more by curiosity, joy and wonder than rational regard for his personal safety. And finally, this is one of a number of his poems where he is taking his clothes off, skinny dipping, walking naked through a forest, and so on. I think this recurring image is a way of expressing his longing for an unmediated encounter with the world around him. It combines his transparency and his desire for oneness with nature.

There are several longer poems here, some narrative poems. One of the long narrative poems, “And We Were Nearly Children,” is among the most moving things I’ve ever read. If it doesn’t break your heart, you must not have one. It concerns the story of his wife’s first pregnancy, somewhere back in the 1970s, when natural childbirth, hippie midwifery and a rejection of professional medicine were all the rage. The results are tragic.

This reveals something significant about the psyche that created such poetry, about his desire for wholeness. In a world full of wounding, whether self-inflicted or not, wholeness only comes through healing, and healing comes through openness to truth and beauty, the touchstones of all genuine art. It doesn’t surprise me that in a recent interview he cites Gary Snyder, W. S. Merwin, Czeslaw Milosz, Linda Gregg and Pablo Neruda among the poets that have most influenced him. Interestingly, there is little or no trace of any stylistic artifacts from these influences. Their impact on his work has been at a deeper level.

A note on his poetics and technique: like much of the best poetry written in the past century, Hettich’s poems are in free verse. Or perhaps it would be better to borrow a phrase from Louis Simpson, who preferred “free form” to “free verse.” That is to say, letting each poem discover its own form, usually related to the natural rhythms of speech in phrases delivered line-break by line-break, like breaths. Don’t worry, I’m not going to go all Charles Olson on you. I’ll merely add that in the course of an unusually productive literary lifetime Hettich has proven himself a master. In his hands, this approach to crafting a poem really works. Anyone who cares about this ancient art we writers hold dear will find themselves opened up by the open mind and heart and soul of this poet.

Kurt Luchs (kurtluchs.com) won a 2022 Pushcart Prize, a 2021 James Tate Poetry Prize, the 2021 Eyelands Book Award for Short Fiction, and the 2019 Atlanta Review International Poetry Contest. He is a Senior Editor of Exacting Clam. His humor collection, It’s Funny Until Someone Loses an Eye (Then It’s Really Funny) (2017), and his poetry collection, Falling in the Direction of Up (2021), are published by Sagging Meniscus Press. His latest poetry chapbook is The Sound of One Hand Slapping (2022) from SurVision Books (Dublin, Ireland). He lives in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

Michael Hettich

Press 53 2023

By Kurt Luchs

One of the first things you notice about Michael Hettich’s poems is that they cannot easily be summarized or described. I mean that as a compliment. They are completely themselves.

These verses have been so lovingly labored over it is difficult to notice the work that went into them, we feel them come alive and fly. I am reminded of something I learned from The Variorum Edition of the Poems of W. B. Yeats. The poet would often revise his work by removing or toning down the images or phrases in individual lines in order to make the poem stronger. In Hettich’s work, we get the sense of infinite possibility, of how things might very well have been different. And then suddenly, in the next line or the next stanza, they are different, as in the last stanza of “The Dark House”:

or moving through the dark like the moon does, pulling

the tides inside us, oceans we might even

swim out in, naked and warm, until morning

when we’ll be out of sight, so far from shore

our lives might go on without us.

This generous selected poems pulls from all except the first of Hettich’s twelve full-length collections, and all but the first two of his many chapbooks. Reading this marvelous body of work in one go has made me curious as to what was left out. I tried to satisfy my curiosity by ordering what was apparently the last extant copy of his first collection, Lathe, and am eagerly waiting for it.

This new and selected volume opens with a batch of new poems called “The Shape of Moving,” perhaps influenced by his retirement from a lifetime of teaching and subsequent relocation from Florida to Black Mountain, North Carolina. No matter what sparks a Hettich poem, it opens a dimensional door to an inner place where thoughts, feelings, memories, dreams and visions intermingle in surprising, unpredictable ways leaving the the reader transformed. This is a poetry of illumination and transcendence grounded in the things of the earth. In “The River,” Hettich opens the piece like this:

I’m taking a pause from the person I’ve been

for most of my life and starting to enter

the man I’ve been only occasionally, even

the man I’ve only pretended to be--

a stranger I’ve hardly imagined.

It turns out his wife—a frequent presence throughout his work—is undergoing the same mysterious change. They agree to do it together, whatever it is. The middle of the poem offers some clues:

The river that runs by our house has been rising

for weeks. We’ve been cleaning out our closets,

tossing things into the swirl:

old books we thought we should love, classics

that only bored us, as they’ve bored everyone

for centuries […]

And then comes a typical Hettich ending, if there is such a thing, an ending that is really more of a beginning based on a new consciousness, a new awareness:

Even our faces in the mirror seem

to have been swept away now by that rising river

and by our yearning. I can only be naked,

though I’m trying to locate the clothes I wore

when I was a man who sported perfect teeth

and a full head of hair, the kind who tells the truth

when he lies—or vice versa, I can’t remember now,

though I’m sure it must matter to someone.

I want to single out some of the poems in this book that struck me most strongly. From the opening of “The Stone Wall,” one of the new poems:

I am coming to the end of something, I can feel it

like a bone that was useful in the past, that kept me

standing upright but has turned into a toothpick

or a splinter dissolving in my blood […]

Here are some lines from the middle of “The Bullfrogs,” about his initial experiences in the Everglades with his wife after moving to Florida. First he tells us “every time / we pulled off the road there, we had to take off / our clothes for a swim in the black water […]. Then:

We marveled at the fact that so few people

came out here to swim: The water smelled like flowers.

For that whole first year we had no idea

those croaks we found so charming were actually

challenges from bull alligators establishing their territory,

calling anything in the immediate vicinity

to make love or fight, and they were hungry too.

This is a very representative a Hettich poem in several ways. First of all, for its candor and his willingness to tell self-deprecating tales. Secondly for his immersion in the natural world, both literally and figuratively, motivated more by curiosity, joy and wonder than rational regard for his personal safety. And finally, this is one of a number of his poems where he is taking his clothes off, skinny dipping, walking naked through a forest, and so on. I think this recurring image is a way of expressing his longing for an unmediated encounter with the world around him. It combines his transparency and his desire for oneness with nature.

There are several longer poems here, some narrative poems. One of the long narrative poems, “And We Were Nearly Children,” is among the most moving things I’ve ever read. If it doesn’t break your heart, you must not have one. It concerns the story of his wife’s first pregnancy, somewhere back in the 1970s, when natural childbirth, hippie midwifery and a rejection of professional medicine were all the rage. The results are tragic.

This reveals something significant about the psyche that created such poetry, about his desire for wholeness. In a world full of wounding, whether self-inflicted or not, wholeness only comes through healing, and healing comes through openness to truth and beauty, the touchstones of all genuine art. It doesn’t surprise me that in a recent interview he cites Gary Snyder, W. S. Merwin, Czeslaw Milosz, Linda Gregg and Pablo Neruda among the poets that have most influenced him. Interestingly, there is little or no trace of any stylistic artifacts from these influences. Their impact on his work has been at a deeper level.

A note on his poetics and technique: like much of the best poetry written in the past century, Hettich’s poems are in free verse. Or perhaps it would be better to borrow a phrase from Louis Simpson, who preferred “free form” to “free verse.” That is to say, letting each poem discover its own form, usually related to the natural rhythms of speech in phrases delivered line-break by line-break, like breaths. Don’t worry, I’m not going to go all Charles Olson on you. I’ll merely add that in the course of an unusually productive literary lifetime Hettich has proven himself a master. In his hands, this approach to crafting a poem really works. Anyone who cares about this ancient art we writers hold dear will find themselves opened up by the open mind and heart and soul of this poet.

Kurt Luchs (kurtluchs.com) won a 2022 Pushcart Prize, a 2021 James Tate Poetry Prize, the 2021 Eyelands Book Award for Short Fiction, and the 2019 Atlanta Review International Poetry Contest. He is a Senior Editor of Exacting Clam. His humor collection, It’s Funny Until Someone Loses an Eye (Then It’s Really Funny) (2017), and his poetry collection, Falling in the Direction of Up (2021), are published by Sagging Meniscus Press. His latest poetry chapbook is The Sound of One Hand Slapping (2022) from SurVision Books (Dublin, Ireland). He lives in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

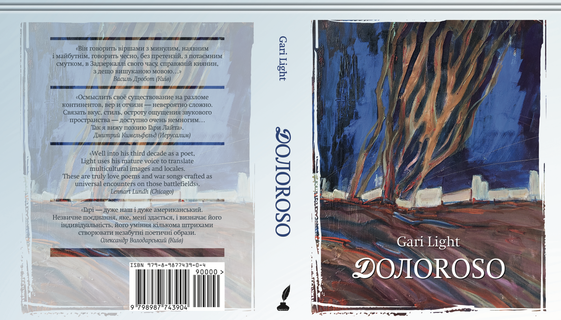

The naming of things by Gary Light

By Jenya Krein (Boston)

Gari Light’s new trilingual poetry collection Doloroso, published simultaneously in Ukraine and in the U.S., is an assortment of whimsical vignettes fused together with elements of poetry, essay, and philosophy.

Born in Kyiv, then very much a part of the Soviet totalitarian state, Light came to America at the age of 12 with his parents at the end of the ‘70s.

In his new collection, he examines his roots, reminiscences about his childhood in the Soviet Union.

Kyiv, the city of golden domes, the “New Jerusalem” or “Jerusalem of the North,” appears time and time again. In some ways, it reminds me of Nabokov’s early writings.

My connection to Light took place during the last two years, coinciding with the pandemic. The quarantines and lockdowns made the usual interactions virtual. Our connection came not from the Covid-19 outbreak but from the war in Ukraine that forced us to review our deepest convictions, moral and political views in such a way that it irrevocably changed not just our outlook but who we were and who we are becoming now:

We haven’t walked those sands, sufficiently enough,

haven’t quite felt the essence of the desert deep down inside.

The front-line artillery rounds were loaded with blanks.

The truly good and kind were no longer the preferred choice,

just as that old feeling of empathy wasn’t missed when it vanished

That awkward listing of apparent triumphs was so lonely and rash

that the resulting moral lapses would not be absolved with tears in time.

This poem, written in 2017, Light attributes to the “perpetual waves of artistic introspection.”

Our need for truth and connection, for harmony and beauty is especially evident in times of war and chaos. During political and societal crisis, we choose poetry almost instinctively. It’s our intrinsic need for fairness, justice, and human connection.

The naming of things though nostalgic for Light, is strictly personal for me. The naming of things is a slippery slope because it’s fraught with trigger points.

Perhaps it is not even nostalgia, but rather a version of a world imagined, that nebulous pondering of collective images of how things may have been:

We haven’t walked those sands, sufficiently enough…

And all the while that fairytale was set in biblical proportions,

the Pharisaism went unheeded, but for the perception of light.

Darkness managed to hide itself quite well in distant corners,

hinting of its impending arrival in periodic ghoulish outbursts.

Arrived, it did, November evening, in the feeble count of votes,

and was distributed so loudly that some have chosen not to hear at all.

That time, which is adjusting still… The fort abandoned, not yet taken,

the books of longing and forgiving, have not been ordered yet to burn…

As the draft decree is still lacking that coma, not that grammar matters,

and when it all becomes a roar, when all indulgences have been granted…

There is a recurrent connection to the prose and poetry of experimentalist Arkadii Dragomoshchenko here. And drawing upon classical lines of Mikhail Lermotov, who had gone to Soviet schools in the 60’s and 70’s, Light writes:

Werther is already written, the sail is white,

it all would work out on other occasions.

That crack in the name—time is certainly trite,

If even the setting is slightly voracious.

Those childhood dreams with the sea in reflections,

caressing the dock, which had ceased to be coastal,

the meanings no longer debated in sessions

Liszt’s rhapsodies are irreversible, mostly.

Light’s poetry is not an easy read. It takes a dedicated reader to follow his chain of imagery and visions. It’s a refrain of voices, confluences, whispers, and cries. At times he sounds almost naïve, but at other times despondent, even bitter. It’s what happens when you need to keep going while stunned into disbelief and rage. Light’s nostalgie is different than seemingly similar longings of other émigré writers.

All indicators confirm the fact that Paris is gone,

those early flights have quite a lot in common,

the airline coffee appears to be real only to some,

and literary nuances are just like the verbs that summon.

The struggling moon is dissolved in the Scorpio sign,

the month just began and winter is approaching fast,

while all it should take is to be understanding and kind,

as that fugue composed by Bach is a sensory test…

The sorrow is there, but emotions are not named but painted.

Perhaps it’s the incompleteness of a life caught between cultures, tongues, and continents that provides us with Light’s kind of poetry.

“Будет новая проза в клочьях старых стихов,” writes Light. ("There will be a new prose in the shreds of old poetry.” Translation is mine.)

Let’s just get there again—to that unforgettable place,

where the rain, as it falls whispers names on the cobblestone surface,

let’s just get there whenever, be it spring as the lilacs make it insane,

or the fall, when the leaves as they perish, do it through all the magic of seeing…

Let’s just get there again, just to marvel and witness

all those images that are impossible to be described.

By Jenya Krein (Boston)

Gari Light’s new trilingual poetry collection Doloroso, published simultaneously in Ukraine and in the U.S., is an assortment of whimsical vignettes fused together with elements of poetry, essay, and philosophy.

Born in Kyiv, then very much a part of the Soviet totalitarian state, Light came to America at the age of 12 with his parents at the end of the ‘70s.

In his new collection, he examines his roots, reminiscences about his childhood in the Soviet Union.

Kyiv, the city of golden domes, the “New Jerusalem” or “Jerusalem of the North,” appears time and time again. In some ways, it reminds me of Nabokov’s early writings.

My connection to Light took place during the last two years, coinciding with the pandemic. The quarantines and lockdowns made the usual interactions virtual. Our connection came not from the Covid-19 outbreak but from the war in Ukraine that forced us to review our deepest convictions, moral and political views in such a way that it irrevocably changed not just our outlook but who we were and who we are becoming now:

We haven’t walked those sands, sufficiently enough,

haven’t quite felt the essence of the desert deep down inside.

The front-line artillery rounds were loaded with blanks.

The truly good and kind were no longer the preferred choice,

just as that old feeling of empathy wasn’t missed when it vanished

That awkward listing of apparent triumphs was so lonely and rash

that the resulting moral lapses would not be absolved with tears in time.

This poem, written in 2017, Light attributes to the “perpetual waves of artistic introspection.”

Our need for truth and connection, for harmony and beauty is especially evident in times of war and chaos. During political and societal crisis, we choose poetry almost instinctively. It’s our intrinsic need for fairness, justice, and human connection.

The naming of things though nostalgic for Light, is strictly personal for me. The naming of things is a slippery slope because it’s fraught with trigger points.

Perhaps it is not even nostalgia, but rather a version of a world imagined, that nebulous pondering of collective images of how things may have been:

We haven’t walked those sands, sufficiently enough…

And all the while that fairytale was set in biblical proportions,

the Pharisaism went unheeded, but for the perception of light.

Darkness managed to hide itself quite well in distant corners,

hinting of its impending arrival in periodic ghoulish outbursts.

Arrived, it did, November evening, in the feeble count of votes,

and was distributed so loudly that some have chosen not to hear at all.

That time, which is adjusting still… The fort abandoned, not yet taken,

the books of longing and forgiving, have not been ordered yet to burn…

As the draft decree is still lacking that coma, not that grammar matters,

and when it all becomes a roar, when all indulgences have been granted…

There is a recurrent connection to the prose and poetry of experimentalist Arkadii Dragomoshchenko here. And drawing upon classical lines of Mikhail Lermotov, who had gone to Soviet schools in the 60’s and 70’s, Light writes:

Werther is already written, the sail is white,

it all would work out on other occasions.

That crack in the name—time is certainly trite,

If even the setting is slightly voracious.

Those childhood dreams with the sea in reflections,

caressing the dock, which had ceased to be coastal,

the meanings no longer debated in sessions

Liszt’s rhapsodies are irreversible, mostly.

Light’s poetry is not an easy read. It takes a dedicated reader to follow his chain of imagery and visions. It’s a refrain of voices, confluences, whispers, and cries. At times he sounds almost naïve, but at other times despondent, even bitter. It’s what happens when you need to keep going while stunned into disbelief and rage. Light’s nostalgie is different than seemingly similar longings of other émigré writers.

All indicators confirm the fact that Paris is gone,

those early flights have quite a lot in common,

the airline coffee appears to be real only to some,

and literary nuances are just like the verbs that summon.

The struggling moon is dissolved in the Scorpio sign,

the month just began and winter is approaching fast,

while all it should take is to be understanding and kind,

as that fugue composed by Bach is a sensory test…

The sorrow is there, but emotions are not named but painted.

Perhaps it’s the incompleteness of a life caught between cultures, tongues, and continents that provides us with Light’s kind of poetry.

“Будет новая проза в клочьях старых стихов,” writes Light. ("There will be a new prose in the shreds of old poetry.” Translation is mine.)

Let’s just get there again—to that unforgettable place,

where the rain, as it falls whispers names on the cobblestone surface,

let’s just get there whenever, be it spring as the lilacs make it insane,

or the fall, when the leaves as they perish, do it through all the magic of seeing…

Let’s just get there again, just to marvel and witness

all those images that are impossible to be described.

May 2023

Yours, Creature, & The Wordless Lullaby of Crickets

Yours, Creature, & The Wordless Lullaby of Crickets

Yours, Creature

Jessica Cuello

Jackleg Press 2023

By Kurt Luchs

What an extraordinary book of poetry! Though the year is still young, this will surely be recognized as one of the best collections published in 2023. Jessica Cuello’s latest is cobbled together like Dr. Frankenstein’s monster from things once living and now reanimated by the inimitable electric imagination of their creator. Or, to put it another way, she has crafted a compelling series of epistolary poems in the haunting voice of Mary Shelley. These verse letters—often addressed to Mary Shelley’s mother, women’s rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft, as well as to countries, cities and times that played central roles in Shelley’s life—add up to much more than a poetic biography, though that in itself would be an ambitious undertaking.

Cuello has also brought to life an era that was truly harrowing for women in general, and particularly for a freethinking, individualistic bohemian like Shelley who faced continual rejection and ostracism for her life choices and sometimes just her life circumstances. Her father, political theorist William Godwin, raised her to think for herself and then coldly turned away when she actually did so. He figures prominently in these poetic missives but it is very telling that none of them are addressed to him. Curiously, neither are any addressed to her lover and eventual husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley, though he too is frequently their subject.

What Cuello has done, then, is to make many of these poems the intimate conversation of one woman to another, or in effect to herself, thinking aloud, mulling over the (mostly) tragic existence she has known. She divides the book into six sections corresponding to major events or periods in Shelley’s life, delving backwards into her parents’ lives before she was born, into her own childhood, and roughly up until the death of Percy in 1822. The first, “A line from the red radius of your womb went dark”, concerns her difficult birth, which her weakened mother survived for less than two weeks. In a way, daughter Mary killed mother Mary, but Cuello has her deflect this painful truth in the last poem of the section, “Dear Mother, [Outside the door]”:

The house is gone that killed you:

red-walled, womb of mauve

I floated inside until it bled like wood

Section two, “Raised by a dictum, but not a man”, tells of Mary Shelley’s father, or “god-of-a-father,” William Godwin, for whom philosophy and ideals were apparently more important than simple human warmth in bringing up children. The ideals did matter to some extent, though. In addition to raising Mary, he also adopted her half-sister, Fanny, born to her mother from a previous alliance. When Godwin remarried, his new wife also came with a stepsister for Mary and Fanny: Claire. The fortunes and misfortunes of these three sisters would be forever intertwined. Meanwhile, the stepmother is a terror, inflicting mental and physical cruelty: “Her latch on me is fixed and I learn to regard myself / with her repulsion” (from “Dear Mother, [I am threatened]”). Percy Bysshe Shelley makes his memorable entrance in this section as well in “Dear Mother, [Silence was my pride]”:

[…] My brain

was a carnation on a stem

made my god-of-a-father look at me:

quiet petals and silver pages

I meant to read until I was his perfect

daughter, but P. put one hand beneath

my smock and all the untouched years

responded […]

From here the pace quickens and it’s one damned thing after another for Mary—exiled to Scotland in a futile attempt to keep her from Percy; the two of them fleeing to France and Europe with Claire in tow (Percy would have affairs with both the stepsister and the half-sister); returning to England bearing Percy’s child; losing the child prematurely; and finally marrying Percy in 1816, but only after his first wife, Harriet, committed suicide. Cuello captures all this and more, so much more, in poems that have been honed, that cut to the bone in phrase after unforgettable phrase, like these ones from “Dear Mother, [Scratch beneath the surface]”:

Scratch beneath the surface of a man

and there’s no help. P. disappears

when babies die.

Or take this one from section three (“I dangle from his word. My life hangs on the beam of his eye.”) in the poem “Dear Mother, [I left father]”:

The forms of stepsister

beside him in the boat

and his wife at home

meant this god was like

the other gods: thin love

and absent eye

and never enough

god to go around.

Allow me just one more extended quote, from section four (“Absence always could subsume me”) and a poem called “Dear Rejection 1815,”:

In threes they came: the mother, the father,

the holy lover. One by one they cut me loose:

the first went underground without me.

The second couldn’t bear to touch me:

I was monstrous, toddling from bed

with open mouth, a devil girl with spindly

neck. The third was a boy who touched

my thigh to prove that I was nectar-made,

my girlhood gone. He fled whenever I felt

too much. Who can love a second time.

Not until the fifth section, “He filled my center with forget-me-seeds,” do we get seven poems addressed to “Dear Creature,” i.e., Dr. Frankenstein’s monster, her most famous literary creation. And there is one more “Dear Creature” poem in the final section, “And I, in the kitchen, am a genius of famine”. It’s not so much that Cuello has saved the best for last, because the whole book beats like a heart restarted by lightning. Instead, she has saved the things about Mary Shelley that might seem most familiar to us so that she can reinvent and reinterpret them.

Recall that Frankenstein was conceived and begun when Mary Shelley was 18, and first published in 1818 when she was merely 20. Incredible! Like Bram Stoker’s Dracula and the Sherlock Holmes books by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Frankenstein became one of the most perennially popular works of fiction of all time. Scarcely a year goes by when a new version of it is not launched on stage or on film. The flip side of that kind of fame is that it puts all of an author’s other works in the shadows. Mary Shelley lived to be 53—unlike her luckless husband, drowned at 29—and wrote more than half a dozen other works, none of which are widely known today. No matter. With Frankenstein she lives forever.

Indeed, this book of poetry by Jessica Cuello is one more proof of Mary’s immortality. Here the poet has done something altogether new with her tribute, however. Just as Shelley brought her confused, friendless monster to a kind of eternal life, so has Cuello resurrected this talented, tormented, warm and personable woman for us and brought her into clear focus in verse that sings on every page. The recreation of Shelley’s voice and manner is uncanny. And very deft. The lines of these striking free verse poems are short and light, the better to balance the heavy sorrow and anguish and despair they carry. The overall effect, oddly, is not downbeat, but purging, regenerative, and ultimately exhilarating.

Kurt Luchs (kurtluchs.com) won a 2022 Pushcart Prize, a 2021 James Tate Poetry Prize, the 2021 Eyelands Book Award for Short Fiction, and the 2019 Atlanta Review International Poetry Contest. He is a Senior Editor of Exacting Clam. His humor collection, It’s Funny Until Someone Loses an Eye (Then It’s Really Funny) (2017), and his poetry collection, Falling in the Direction of Up (2021), are published by Sagging Meniscus Press. His latest poetry chapbook is The Sound of One Hand Slapping (2022) from SurVision Books (Dublin, Ireland). He lives in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

Jessica Cuello

Jackleg Press 2023

By Kurt Luchs

What an extraordinary book of poetry! Though the year is still young, this will surely be recognized as one of the best collections published in 2023. Jessica Cuello’s latest is cobbled together like Dr. Frankenstein’s monster from things once living and now reanimated by the inimitable electric imagination of their creator. Or, to put it another way, she has crafted a compelling series of epistolary poems in the haunting voice of Mary Shelley. These verse letters—often addressed to Mary Shelley’s mother, women’s rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft, as well as to countries, cities and times that played central roles in Shelley’s life—add up to much more than a poetic biography, though that in itself would be an ambitious undertaking.

Cuello has also brought to life an era that was truly harrowing for women in general, and particularly for a freethinking, individualistic bohemian like Shelley who faced continual rejection and ostracism for her life choices and sometimes just her life circumstances. Her father, political theorist William Godwin, raised her to think for herself and then coldly turned away when she actually did so. He figures prominently in these poetic missives but it is very telling that none of them are addressed to him. Curiously, neither are any addressed to her lover and eventual husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley, though he too is frequently their subject.

What Cuello has done, then, is to make many of these poems the intimate conversation of one woman to another, or in effect to herself, thinking aloud, mulling over the (mostly) tragic existence she has known. She divides the book into six sections corresponding to major events or periods in Shelley’s life, delving backwards into her parents’ lives before she was born, into her own childhood, and roughly up until the death of Percy in 1822. The first, “A line from the red radius of your womb went dark”, concerns her difficult birth, which her weakened mother survived for less than two weeks. In a way, daughter Mary killed mother Mary, but Cuello has her deflect this painful truth in the last poem of the section, “Dear Mother, [Outside the door]”:

The house is gone that killed you:

red-walled, womb of mauve

I floated inside until it bled like wood

Section two, “Raised by a dictum, but not a man”, tells of Mary Shelley’s father, or “god-of-a-father,” William Godwin, for whom philosophy and ideals were apparently more important than simple human warmth in bringing up children. The ideals did matter to some extent, though. In addition to raising Mary, he also adopted her half-sister, Fanny, born to her mother from a previous alliance. When Godwin remarried, his new wife also came with a stepsister for Mary and Fanny: Claire. The fortunes and misfortunes of these three sisters would be forever intertwined. Meanwhile, the stepmother is a terror, inflicting mental and physical cruelty: “Her latch on me is fixed and I learn to regard myself / with her repulsion” (from “Dear Mother, [I am threatened]”). Percy Bysshe Shelley makes his memorable entrance in this section as well in “Dear Mother, [Silence was my pride]”:

[…] My brain

was a carnation on a stem

made my god-of-a-father look at me:

quiet petals and silver pages

I meant to read until I was his perfect

daughter, but P. put one hand beneath

my smock and all the untouched years

responded […]

From here the pace quickens and it’s one damned thing after another for Mary—exiled to Scotland in a futile attempt to keep her from Percy; the two of them fleeing to France and Europe with Claire in tow (Percy would have affairs with both the stepsister and the half-sister); returning to England bearing Percy’s child; losing the child prematurely; and finally marrying Percy in 1816, but only after his first wife, Harriet, committed suicide. Cuello captures all this and more, so much more, in poems that have been honed, that cut to the bone in phrase after unforgettable phrase, like these ones from “Dear Mother, [Scratch beneath the surface]”:

Scratch beneath the surface of a man

and there’s no help. P. disappears

when babies die.

Or take this one from section three (“I dangle from his word. My life hangs on the beam of his eye.”) in the poem “Dear Mother, [I left father]”:

The forms of stepsister

beside him in the boat

and his wife at home

meant this god was like

the other gods: thin love

and absent eye

and never enough

god to go around.

Allow me just one more extended quote, from section four (“Absence always could subsume me”) and a poem called “Dear Rejection 1815,”:

In threes they came: the mother, the father,

the holy lover. One by one they cut me loose:

the first went underground without me.

The second couldn’t bear to touch me:

I was monstrous, toddling from bed

with open mouth, a devil girl with spindly

neck. The third was a boy who touched

my thigh to prove that I was nectar-made,

my girlhood gone. He fled whenever I felt

too much. Who can love a second time.

Not until the fifth section, “He filled my center with forget-me-seeds,” do we get seven poems addressed to “Dear Creature,” i.e., Dr. Frankenstein’s monster, her most famous literary creation. And there is one more “Dear Creature” poem in the final section, “And I, in the kitchen, am a genius of famine”. It’s not so much that Cuello has saved the best for last, because the whole book beats like a heart restarted by lightning. Instead, she has saved the things about Mary Shelley that might seem most familiar to us so that she can reinvent and reinterpret them.

Recall that Frankenstein was conceived and begun when Mary Shelley was 18, and first published in 1818 when she was merely 20. Incredible! Like Bram Stoker’s Dracula and the Sherlock Holmes books by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Frankenstein became one of the most perennially popular works of fiction of all time. Scarcely a year goes by when a new version of it is not launched on stage or on film. The flip side of that kind of fame is that it puts all of an author’s other works in the shadows. Mary Shelley lived to be 53—unlike her luckless husband, drowned at 29—and wrote more than half a dozen other works, none of which are widely known today. No matter. With Frankenstein she lives forever.

Indeed, this book of poetry by Jessica Cuello is one more proof of Mary’s immortality. Here the poet has done something altogether new with her tribute, however. Just as Shelley brought her confused, friendless monster to a kind of eternal life, so has Cuello resurrected this talented, tormented, warm and personable woman for us and brought her into clear focus in verse that sings on every page. The recreation of Shelley’s voice and manner is uncanny. And very deft. The lines of these striking free verse poems are short and light, the better to balance the heavy sorrow and anguish and despair they carry. The overall effect, oddly, is not downbeat, but purging, regenerative, and ultimately exhilarating.

Kurt Luchs (kurtluchs.com) won a 2022 Pushcart Prize, a 2021 James Tate Poetry Prize, the 2021 Eyelands Book Award for Short Fiction, and the 2019 Atlanta Review International Poetry Contest. He is a Senior Editor of Exacting Clam. His humor collection, It’s Funny Until Someone Loses an Eye (Then It’s Really Funny) (2017), and his poetry collection, Falling in the Direction of Up (2021), are published by Sagging Meniscus Press. His latest poetry chapbook is The Sound of One Hand Slapping (2022) from SurVision Books (Dublin, Ireland). He lives in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

Guest Review by Judy Ireland

|

REVIEW: THE WORDLESS LULLABY OF CRICKETS, YVONNE ZIPTER

The poetry in Yvonne Zipter’s new book, The Wordless Lullaby of Crickets, Kelsay Books (February 2023) teeters between past and present, humor and sorrow, hurt and healing. Blues guitarists bend soulful notes. Lesbians chop their names off the ends of love letters, erasing themselves. This book teems with life as it invokes the specter of death. The contrast between a woman in cancer treatment with the comfort of her wife coexists with a menagerie of animals, birds, and insects along the way. For those familiar with Yvonne Zipter’s earlier collection, Kissing the Long Face of the Greyhound, this new book is a second serving of serious verse tinged with humor, hope, and affirmation of life’s value, as burdened as it may be. Conversations heat up as we encounter the worst that can happen to a child, to an adult. “words became my pilot light” (“Traveling Library”) as in the poem, “Deliverance.” "I have walked through fire this year, coming out not cleansed but singed, grateful, in any case, to be alive." In “A Brief History of the War on Women, ” a way forward is found through language, as it is found in books by the victimized girl-child: “….Only later will she learn to fear her own body, to crawl inside a book like a bomb shelter to save herself from the burning of her happy childhood.” The reader is chilled at the end of the next poem, “Stepfather”, in which the abuser excuses himself: "…It’s not easy, he said, to raise another man’s daughter, as if she should’ve been grateful for his attention." The second section of this book contains poems about the body and the experience of cancer during the time of Covid. The hospital becomes a temple in “Sacred Space,” and drugs used to treat cancer become “amulets / against the evils of nausea and vomiting” in “Devotional.” In that same poem, we see a poet who rose: "Lazurus-like and walked toward the light // in the living room and raised the word with me, writing poems like prayers of thanksgiving // for the knives, the needles, and the knowledge and for the wizards who wielded them." Emerson believed that every natural fact “is a symbol of some spiritual fact” and that “the whole of nature is a metaphor of the human mind” (“Nature”). The poems in the third section of Yvonne Zipter’s book engage with the objects of nature as both realities in themselves and as symbols. The spirituality of these poems is natural and transcendent, as in “The Kestrel”: “…it is hard to see the luck for the sparrow in this, its wilted body draped over the bark like an offering to an unsentimental god, while the raptor – bowing her head in a prayer of gratification – catches the sun (someone else’s god) on her rust- and slate-colored head, all the holy days of our childhoods insignificant in the single yellow rosary bead of her eye." Earlier, in “Saints and Fire,” the poet notes, “A bird isn’t a miracle.” But exploring the psyche's healing and mending that occurs within the observation of the bird, the poet asks, “isn’t that a kind of wonder?” Emerson wrote that “all objects shrink and expand to serve the passion of the poet.” In this collection, Zipter’s brave poems invite us to expand our awareness of life, its creatures, its inevitabilities, and its joyful wonders. |

February 2023

Guest Review by Judy Ireland

|