Issue 15 November 2019

Sarah Kersey, Editor

Sarah Kersey, Editor

Poets in this issue: Kamal E. Kimball, Lukpata Lomba Joseph, Linda Pastan, Mela Blust, Alisa Veilja, Bruce Bond, Lyn Lifshin, Catherine Mazodier, Tim Kahl, Kushal Poddar, Laura Ohlmann, Keith Ratzlaff, Paul Dickey, Mark DeCarteret, Daniel Edmond Moore, Kevin Gidusko

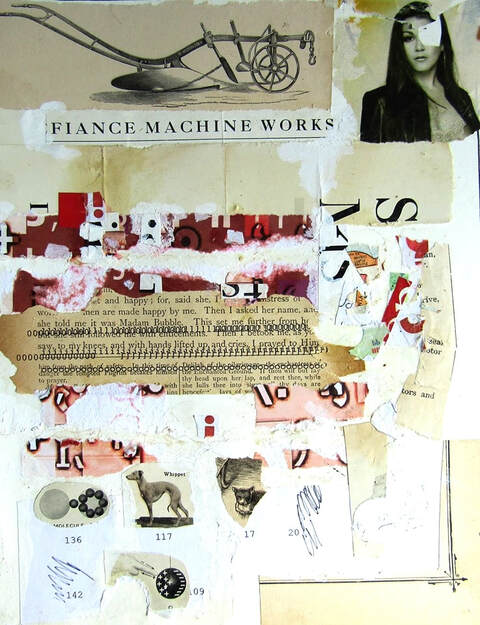

DVS1 Collage by De Villo Sloan

SoFloPoJo Rejected Poem Project

For the November 2019 issue, we asked poets to send one poem that had been rejected by at least one other literary magazine. We chose only one poem from those we received. The poem we selected is Kamal E. Kimbal's "No Gods, No Masters."

The idea to publish a rejected poem is not original on our part. Redheaded Stepchild publishes only poems that have been rejected by other journals. It's a great idea.

The idea to publish a rejected poem is not original on our part. Redheaded Stepchild publishes only poems that have been rejected by other journals. It's a great idea.

Kamal E. Kimball

No Gods, No Masters

She feels like a dog. She needs to eat.

She has learned how to gnaw, can sense

who deserves it, can scent the lime

stench of their fear, thin as cologne.

She loves to say loin until her lips film

with oil and she feels like a lion, her teeth

too huge for her jaw. She thrusts

her hands into fire. She feeds it undug bones.

It takes all night. There are many

graves to piss on. There is little time.

The fire grows. She grows. They burn

down her daddy’s trailer, ash his name.

She is very tired and fond of her cage,

only when she lets herself

clench and then unglove. She is feral

to be seen. She loves it best

when she gets very nude in rooms

of eyes and fog. Most rooms are

mostly empty. Most things when you look

for a bottom. In them, she wore

her chains like a cramp of pearls.

She coined new words for how

she preferred to be hurt.

But she knows how to open

the doors now. She is not afraid

to sleep in the snow.

Rejected by Radar

Kamal E. Kimball is a poet and teacher based in Columbus, Ohio. A production editor for The Journal and reader for Muzzle Magazine, her work has been published or is forthcoming in Rattle, Phoebe, Hobart, Juked, Tahoma Literary Review, Sundog Lit, Bone Parade, Kaaterskill Basin Literary Journal, Forklift, Ohio, and elsewhere. More at kamalkimball.com

She feels like a dog. She needs to eat.

She has learned how to gnaw, can sense

who deserves it, can scent the lime

stench of their fear, thin as cologne.

She loves to say loin until her lips film

with oil and she feels like a lion, her teeth

too huge for her jaw. She thrusts

her hands into fire. She feeds it undug bones.

It takes all night. There are many

graves to piss on. There is little time.

The fire grows. She grows. They burn

down her daddy’s trailer, ash his name.

She is very tired and fond of her cage,

only when she lets herself

clench and then unglove. She is feral

to be seen. She loves it best

when she gets very nude in rooms

of eyes and fog. Most rooms are

mostly empty. Most things when you look

for a bottom. In them, she wore

her chains like a cramp of pearls.

She coined new words for how

she preferred to be hurt.

But she knows how to open

the doors now. She is not afraid

to sleep in the snow.

Rejected by Radar

Kamal E. Kimball is a poet and teacher based in Columbus, Ohio. A production editor for The Journal and reader for Muzzle Magazine, her work has been published or is forthcoming in Rattle, Phoebe, Hobart, Juked, Tahoma Literary Review, Sundog Lit, Bone Parade, Kaaterskill Basin Literary Journal, Forklift, Ohio, and elsewhere. More at kamalkimball.com

November poems

Lukpata Lomba Joseph 2 poems

A Story on Fire

(For Nigeria)

I wanted to write a condensed

story on fire,

and it was easy to see

a hat of thorns

a man hammered to a bar

and a three-days' sojourn

all in a free flow.

Then, this left scrappy

shapes on page,

skeletons of dead religious tropes

and too many unmeaning things.

My professor who grew up in Rome

would scream disgraziata

and I know it shouldn't be

about a man or a bar,

but yellow sand and yellow sky,

wrecks of broken history and culture

heaped to form gods thirsty for tears.

In the north, a white dove

was caught and caged,

the very last of its species.

Its bones have been milled

to form yellow dust

(we must salaam

to dust

whose bare skin

we will all embrace)

And we must learn

the act of selfless love,

we must love for love.

We must search for love by death

and death by love.

And we must learn

the act of selfless love.

We must love guns, contraband, death.

I wanted to write a

story on fire and my professor

said it must start with broken pieces,

caged dove and gods of tears.

Its plot must be linear

—just a land of fire, guns and death;

a dovetail of uneven fitting,

and a staggering flag

lurching to serve a new god.

Note: The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines “salaam” as “an obeisance performed by bowing very low.”

In my poem, I used the verb form of the same word which the Merriam-Webster Dictionary also defines as “to greet or pay homage to with a salaam.”

I like to think of this word as having derived its meaning from Islamic tradition, their pattern of greeting which is more like kowtowing but not exactly.

Of course, a close look at the word reveals that it originated from Arabic “salam” (literally “peace”) which in a deeper sense has connection with the Islamic tradition.

To further answer your question, I used that word after I had talked of a white dove that was caught and caged, (Lack of peace in the northern part of Nigeria is the backdrop to this symbolic usage, where I used “a dove” to symbolize peace).

Of course, the absence of peace in the north is as a result of the activities of the Islamic terrorist group, Boko Haram. They are against Western Education (at least this is the knowledge we hold at the moment).

We must bow to dust just like the white dove has been milled to dust already. And of course, we will surely bow to dust from their suicide bombings and attacks in public places.

My choice of the word “salaam” over “bow” was informed by my desire to create a connection, what I like to call “a coded imagery”.

(For Nigeria)

I wanted to write a condensed

story on fire,

and it was easy to see

a hat of thorns

a man hammered to a bar

and a three-days' sojourn

all in a free flow.

Then, this left scrappy

shapes on page,

skeletons of dead religious tropes

and too many unmeaning things.

My professor who grew up in Rome

would scream disgraziata

and I know it shouldn't be

about a man or a bar,

but yellow sand and yellow sky,

wrecks of broken history and culture

heaped to form gods thirsty for tears.

In the north, a white dove

was caught and caged,

the very last of its species.

Its bones have been milled

to form yellow dust

(we must salaam

to dust

whose bare skin

we will all embrace)

And we must learn

the act of selfless love,

we must love for love.

We must search for love by death

and death by love.

And we must learn

the act of selfless love.

We must love guns, contraband, death.

I wanted to write a

story on fire and my professor

said it must start with broken pieces,

caged dove and gods of tears.

Its plot must be linear

—just a land of fire, guns and death;

a dovetail of uneven fitting,

and a staggering flag

lurching to serve a new god.

Note: The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines “salaam” as “an obeisance performed by bowing very low.”

In my poem, I used the verb form of the same word which the Merriam-Webster Dictionary also defines as “to greet or pay homage to with a salaam.”

I like to think of this word as having derived its meaning from Islamic tradition, their pattern of greeting which is more like kowtowing but not exactly.

Of course, a close look at the word reveals that it originated from Arabic “salam” (literally “peace”) which in a deeper sense has connection with the Islamic tradition.

To further answer your question, I used that word after I had talked of a white dove that was caught and caged, (Lack of peace in the northern part of Nigeria is the backdrop to this symbolic usage, where I used “a dove” to symbolize peace).

Of course, the absence of peace in the north is as a result of the activities of the Islamic terrorist group, Boko Haram. They are against Western Education (at least this is the knowledge we hold at the moment).

We must bow to dust just like the white dove has been milled to dust already. And of course, we will surely bow to dust from their suicide bombings and attacks in public places.

My choice of the word “salaam” over “bow” was informed by my desire to create a connection, what I like to call “a coded imagery”.

A Letter to a Horse Rider

‘Death forgive me-

For making jokes about you being

The elder brother of sleep.

Sleep is where dreams live.

You kill dreams.

You and sleep are not related.’—Moyosore.

I want to write a song

for you, the last enemy.

I was just three; I didn’t know you

and I had to ask about dad.

They said the rider of a pale horse visited.

Why do you like blank spaces?

You are no small thing,

you are the only one of your breed

and there’s only one way you can go--

through fresh bones, leaving shafts.

How do you eat your meat?

You are powerful,

the greatest thaumaturge.

But you are not a good listener,

you didn’t hear that she just got married.

The horse rider has no hope of improving

his timing by listening,

he is not a good listener.

You filter through unfettered,

and you savour the short

and labored breathing, glow of despair

as you send away all 21 grams on exile.

But you don’t value courtesy,

you don’t know your worth,

don’t even know when you aren’t welcome.

You should have a lot to fuss about:

the schemes you’ve truncated, the lack of cronies

and your pale horse—you may as well want

to hollow through its bones.

You give fame. At your kiss, everyone will hear us.

But you don’t know how to earn fame,

you can only earn curses

because you are not a good listener.

Author’s Note:

Lukpata Lomba Joseph lives in Nigeria. He is a contributing writer to an online weekly magazine, Joshua’s Truth. Many of his poems explore the concept of internal noise in diverse forms. His work has appeared in Poetry North Ireland’s FourXFour Journal, Caustic Frolic Literary Journal, Still Point Magazine, Vox Poetica and elsewhere. Recently, he has fallen in love with satirical writing with a deliberate focus on morality. He likes reading Aesop’s fables. You can find him on Facebook at www.facebook.com/lukpata.joseph.9.

‘Death forgive me-

For making jokes about you being

The elder brother of sleep.

Sleep is where dreams live.

You kill dreams.

You and sleep are not related.’—Moyosore.

I want to write a song

for you, the last enemy.

I was just three; I didn’t know you

and I had to ask about dad.

They said the rider of a pale horse visited.

Why do you like blank spaces?

You are no small thing,

you are the only one of your breed

and there’s only one way you can go--

through fresh bones, leaving shafts.

How do you eat your meat?

You are powerful,

the greatest thaumaturge.

But you are not a good listener,

you didn’t hear that she just got married.

The horse rider has no hope of improving

his timing by listening,

he is not a good listener.

You filter through unfettered,

and you savour the short

and labored breathing, glow of despair

as you send away all 21 grams on exile.

But you don’t value courtesy,

you don’t know your worth,

don’t even know when you aren’t welcome.

You should have a lot to fuss about:

the schemes you’ve truncated, the lack of cronies

and your pale horse—you may as well want

to hollow through its bones.

You give fame. At your kiss, everyone will hear us.

But you don’t know how to earn fame,

you can only earn curses

because you are not a good listener.

Author’s Note:

- The pale horse rider is an allusion to Revelation 6:8, where death was described as the rider of a pale horse with hades following him.

- The concept of the human soul weighing 21 grams was popularized by Duncan MacDougall, a U.S. physician. In 1907, he attempted to measure the weight of the human soul by measuring the weight lost by patients after death. Although, his experiment was widely described as unscientific, it gave birth to the concept of the human soul weighing 21 grams.

Lukpata Lomba Joseph lives in Nigeria. He is a contributing writer to an online weekly magazine, Joshua’s Truth. Many of his poems explore the concept of internal noise in diverse forms. His work has appeared in Poetry North Ireland’s FourXFour Journal, Caustic Frolic Literary Journal, Still Point Magazine, Vox Poetica and elsewhere. Recently, he has fallen in love with satirical writing with a deliberate focus on morality. He likes reading Aesop’s fables. You can find him on Facebook at www.facebook.com/lukpata.joseph.9.

Linda Pastan

tulips in a glass vase

their huge, tear-shaped

petals fall

all over the rug

these tulips

in the last throes

of life

weeping

their colors—flame,

purple, creamy white--

while outside

spring

in all its ornamental

mania

blossoms on

and on without them

Linda Pastan won the Mademoiselle poetry prize (Sylvia Plath was the runner-up). Her many awards include the Dylan Thomas award and the Ruth Lily Poetry Prize, in 2003. Pastan served as Poet Laureate of Maryland from 1991 to 1995 and was on the staff of the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference for 20 years. She is the author of more than 15 books of poetry and essays. Her PM/AM: New and Selected Poems (1982) and Carnival Evening: New and Selected Poems 1968–1998 (1998) were finalists for the National Book Award; The Imperfect Paradise (1988) was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. Her recent collections include The Last Uncle (2001), Queen of a Rainy Country (2006), Traveling Light (2011), Insomnia (2015), and A Dog Runs Through It (2018). She lives in Chevy Chase, Maryland.

their huge, tear-shaped

petals fall

all over the rug

these tulips

in the last throes

of life

weeping

their colors—flame,

purple, creamy white--

while outside

spring

in all its ornamental

mania

blossoms on

and on without them

Linda Pastan won the Mademoiselle poetry prize (Sylvia Plath was the runner-up). Her many awards include the Dylan Thomas award and the Ruth Lily Poetry Prize, in 2003. Pastan served as Poet Laureate of Maryland from 1991 to 1995 and was on the staff of the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference for 20 years. She is the author of more than 15 books of poetry and essays. Her PM/AM: New and Selected Poems (1982) and Carnival Evening: New and Selected Poems 1968–1998 (1998) were finalists for the National Book Award; The Imperfect Paradise (1988) was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. Her recent collections include The Last Uncle (2001), Queen of a Rainy Country (2006), Traveling Light (2011), Insomnia (2015), and A Dog Runs Through It (2018). She lives in Chevy Chase, Maryland.

Mela Blust 4 poems

autumn

i waited by the shadow of your mouth

buried under a deep, pensive blanket

but you were a petal already fallen

from a flower i could not name

your language of unfinished breath

a scythe rusting in the field

the somehow echo of us

a pull-cord broken at the light

i waited by the shadow of your mouth

buried under a deep, pensive blanket

but you were a petal already fallen

from a flower i could not name

your language of unfinished breath

a scythe rusting in the field

the somehow echo of us

a pull-cord broken at the light

motherhood

crumpled and matted before me,

an offering no one

ever asks for

melding with the road, wet

and wetter as

my tears fall

how silent it can be even with

cars rushing by

casting wariness aside for compassion

as i tenderly scoop the only days old fawn

from the pavement

its crushed limbs dangling across

my motherly arms

and i put someone's angel

delicately into

the soft meadow grass

as though it never left.

crumpled and matted before me,

an offering no one

ever asks for

melding with the road, wet

and wetter as

my tears fall

how silent it can be even with

cars rushing by

casting wariness aside for compassion

as i tenderly scoop the only days old fawn

from the pavement

its crushed limbs dangling across

my motherly arms

and i put someone's angel

delicately into

the soft meadow grass

as though it never left.

no child

i was kissed by the music of war

while praying for man

as useless as tar stuck to the hands

as useless as hands in the shape of a gun

rounds like the seconds of a grandfather clock ticking away

a stomach

some raven perched on the hairs of my neck;

a blood canticle for selfish comfort

later, a sigh

anymore

no child has a song of honey

no language, a thirst for god.

i was kissed by the music of war

while praying for man

as useless as tar stuck to the hands

as useless as hands in the shape of a gun

rounds like the seconds of a grandfather clock ticking away

a stomach

some raven perched on the hairs of my neck;

a blood canticle for selfish comfort

later, a sigh

anymore

no child has a song of honey

no language, a thirst for god.

lies we tell ourselves

you tried to make me so small

stitched me into the tightest of blankets

Hiding my curves behind

angles and light

crow's wing hair,

bee stung lips

Ashamed of hunger, hungry for joy

denying me so much

denying me sustenance

shiny curls hiding hollowed out cheekbones

later, my throat swallows itself

I'd say it's killing me but

I've been dead for years, hiding inside my stomach

scissor cut and scissor tongue -

lies we tell ourselves about being too much

You couldn't love me because there was so much of me.

So you carved fault lines, breathed white lines

told little white lies.

separated me from god,

made me someone else.

Mela Blust's work has appeared in The Bitter Oleander, YesPoetry, Isacoustic, Rust+Moth, Anti Heroin Chic, Califragile, Tilde Journal, Setu Magazine, Rhythm & Bones Lit, The Nassau Review, The Sierra Nevada Review, The Stray Branch, more. Her debut poetry collection, Skeleton Parade, is forthcoming with Apep Publications in 2019. She is Head Publicist and Social Media Manager for Animal Heart Press, a contributing editor for Barren Magazine, and a poetry reader for The Rise Up Review. She can be followed at https://twitter.com/melablust.

you tried to make me so small

stitched me into the tightest of blankets

Hiding my curves behind

angles and light

crow's wing hair,

bee stung lips

Ashamed of hunger, hungry for joy

denying me so much

denying me sustenance

shiny curls hiding hollowed out cheekbones

later, my throat swallows itself

I'd say it's killing me but

I've been dead for years, hiding inside my stomach

scissor cut and scissor tongue -

lies we tell ourselves about being too much

You couldn't love me because there was so much of me.

So you carved fault lines, breathed white lines

told little white lies.

separated me from god,

made me someone else.

Mela Blust's work has appeared in The Bitter Oleander, YesPoetry, Isacoustic, Rust+Moth, Anti Heroin Chic, Califragile, Tilde Journal, Setu Magazine, Rhythm & Bones Lit, The Nassau Review, The Sierra Nevada Review, The Stray Branch, more. Her debut poetry collection, Skeleton Parade, is forthcoming with Apep Publications in 2019. She is Head Publicist and Social Media Manager for Animal Heart Press, a contributing editor for Barren Magazine, and a poetry reader for The Rise Up Review. She can be followed at https://twitter.com/melablust.

Alisa Veilja

Visions of a Storm Petrel

I don't know whence I am coming.

I proclaim the dead creator to be my enemy

from tomorrow onward.

The storm calls me;

the wave soars to the height of my flight,

and then reconverts to plain sea!

Space after space and beyond, the wild storm kicks me off my rocker.

Cradle and grave, grave and light

on the horizon of a wave graph.

The boats on the sandy shore once shattered

my insane love for symmetry.

I've had no time to brood

on whatever could or should come through!

Before and after the storm

the sea is mere water, not mighty wave.

The wave is us,

at the height of our own self.

Translated from Albanian: ARBEN P. LATIFI

Born in 1982 in Albania, Alisa Velaj’s poems have been published in Erbacce, The Curlew, Culture Cult Magazine, Stag Hill Literary Journal, The Quarterly Review, Orbis, The Linnet's Wings, and The Stockholm Review of Literature. She earned an Artist-in-Residence Scholarship, and attended the AIR Litteratur Västra Götaland Program in Villa Martinson, Jonsered, Sweden.

I don't know whence I am coming.

I proclaim the dead creator to be my enemy

from tomorrow onward.

The storm calls me;

the wave soars to the height of my flight,

and then reconverts to plain sea!

Space after space and beyond, the wild storm kicks me off my rocker.

Cradle and grave, grave and light

on the horizon of a wave graph.

The boats on the sandy shore once shattered

my insane love for symmetry.

I've had no time to brood

on whatever could or should come through!

Before and after the storm

the sea is mere water, not mighty wave.

The wave is us,

at the height of our own self.

Translated from Albanian: ARBEN P. LATIFI

Born in 1982 in Albania, Alisa Velaj’s poems have been published in Erbacce, The Curlew, Culture Cult Magazine, Stag Hill Literary Journal, The Quarterly Review, Orbis, The Linnet's Wings, and The Stockholm Review of Literature. She earned an Artist-in-Residence Scholarship, and attended the AIR Litteratur Västra Götaland Program in Villa Martinson, Jonsered, Sweden.

Bruce Bond

From Narcissus in the Underworld: 26, 28, 31, 32, 33

The creak of boats in swells of the harbor

sounds a warning like hinges of a forest

or failed estate. So difficult to get

news from news, history from history,

by which I mean writing and the written

off. The auguries of smoke and wind

blow dust from the glass of eyes that sting.

Earth keeps spinning the storm surge north,

and mountains sink, and refugees come,

and foreign words for home in the distance.

When a shoreline breaks, it breaks open,

and in flow the pixels too small to see,

stars of neither cruelty nor grace, but

a sorrow so deep its name has not arrived.

*

When a high wind tears down the power

and it’s you and me and the emptiness

that gives us license to move, we do not move.

We gather our cats in the pantry, we listen

we hear in heaven the enormous sigh

of an iron lung exhaling, the storm eye

passing, the terrible burden coming to rest.

One part of every wind is trembling.

The other the stillness the trembling moves aside.

The future, as we know it, is never true.

Never false. It is here in the quiet turn

of every breath, the little death a singer breathes.

One part of each departure is a mirror,

the other the wall to which a mirror turns.

*

The affliction of the heretic is never

to see the world at hand, only a world

to come, and so the circle of the damned

whose every step is the one they are

not taking. I have been that man. I

drove so reckless I could have killed my friends.

I love, I said, and it was not love, but

a world without heresy is not the world

I forgive. Call it innocence or sin,

the volt of desire that could have killed us all.

The affliction of the fetishist is never

to reclaim our disbelief. I have been

that angel doused in gasoline, that eye

of the candle, the blindness of the flame.

*

Back when I rented my books, I saw,

in the ledger pasted to the inner cover,

the signatures of students who carried

them before me. And there inside one

I found the name of a famous assassin,

and it made me feel important, as he too

must have felt, for all the wrong reasons.

I touched the hand that touched the gun that touched

the better nation we might have been.

If I hated the man behind the name,

I did not feel it. I could not yet. I was

a star. Today’s lesson is about the power

of the name, my teacher said. And so,

without warning, he took my book away.

*

The photo of a man turns to the wall,

so weary of the gazing and the gazed.

That spirit of exchange you hear about

in poems, it cannot hear you. Poems go

to die in silence and in dirt. I hate that.

I hate it and honor it, whatever it takes

to pay attention. The greatest poverty,

I know, is idolatrous life. I could have

passed my suicidal friend in the street,

and I did not see him. If I gave a dollar

to my assassin, a there-but-for-the-grace

might have kept me from his eyes. A wind

could sweep the street of cigarettes, and I,

a dollar lighter, would shudder out of view.

Bruce Bond is the author of twenty-three books including, most recently, Immanent Distance: Poetry and the Metaphysics of the Near at Hand (U of MI, 2015), Black Anthem (Tampa Review Prize, U of Tampa, 2016), Gold Bee (Helen C. Smith Award, Crab Orchard Award, SIU Press, 2016), Sacrum (Four Way, 2017), Blackout Starlight: New and Selected Poems 1997-2015 (L.E. Phillabaum Award, LSU, 2017), Rise and Fall of the Lesser Sun Gods (Elixir Book Prize, Elixir Press, 2018), Dear Reader (Free Verse Editions, 2018), and Frankenstein’s Children (Lost Horse, 2018). Five books are forthcoming including Plurality and the Poetics of Self (Palgrave). Presently he is a Regents Professor of English at the University of North Texas.

The creak of boats in swells of the harbor

sounds a warning like hinges of a forest

or failed estate. So difficult to get

news from news, history from history,

by which I mean writing and the written

off. The auguries of smoke and wind

blow dust from the glass of eyes that sting.

Earth keeps spinning the storm surge north,

and mountains sink, and refugees come,

and foreign words for home in the distance.

When a shoreline breaks, it breaks open,

and in flow the pixels too small to see,

stars of neither cruelty nor grace, but

a sorrow so deep its name has not arrived.

*

When a high wind tears down the power

and it’s you and me and the emptiness

that gives us license to move, we do not move.

We gather our cats in the pantry, we listen

we hear in heaven the enormous sigh

of an iron lung exhaling, the storm eye

passing, the terrible burden coming to rest.

One part of every wind is trembling.

The other the stillness the trembling moves aside.

The future, as we know it, is never true.

Never false. It is here in the quiet turn

of every breath, the little death a singer breathes.

One part of each departure is a mirror,

the other the wall to which a mirror turns.

*

The affliction of the heretic is never

to see the world at hand, only a world

to come, and so the circle of the damned

whose every step is the one they are

not taking. I have been that man. I

drove so reckless I could have killed my friends.

I love, I said, and it was not love, but

a world without heresy is not the world

I forgive. Call it innocence or sin,

the volt of desire that could have killed us all.

The affliction of the fetishist is never

to reclaim our disbelief. I have been

that angel doused in gasoline, that eye

of the candle, the blindness of the flame.

*

Back when I rented my books, I saw,

in the ledger pasted to the inner cover,

the signatures of students who carried

them before me. And there inside one

I found the name of a famous assassin,

and it made me feel important, as he too

must have felt, for all the wrong reasons.

I touched the hand that touched the gun that touched

the better nation we might have been.

If I hated the man behind the name,

I did not feel it. I could not yet. I was

a star. Today’s lesson is about the power

of the name, my teacher said. And so,

without warning, he took my book away.

*

The photo of a man turns to the wall,

so weary of the gazing and the gazed.

That spirit of exchange you hear about

in poems, it cannot hear you. Poems go

to die in silence and in dirt. I hate that.

I hate it and honor it, whatever it takes

to pay attention. The greatest poverty,

I know, is idolatrous life. I could have

passed my suicidal friend in the street,

and I did not see him. If I gave a dollar

to my assassin, a there-but-for-the-grace

might have kept me from his eyes. A wind

could sweep the street of cigarettes, and I,

a dollar lighter, would shudder out of view.

Bruce Bond is the author of twenty-three books including, most recently, Immanent Distance: Poetry and the Metaphysics of the Near at Hand (U of MI, 2015), Black Anthem (Tampa Review Prize, U of Tampa, 2016), Gold Bee (Helen C. Smith Award, Crab Orchard Award, SIU Press, 2016), Sacrum (Four Way, 2017), Blackout Starlight: New and Selected Poems 1997-2015 (L.E. Phillabaum Award, LSU, 2017), Rise and Fall of the Lesser Sun Gods (Elixir Book Prize, Elixir Press, 2018), Dear Reader (Free Verse Editions, 2018), and Frankenstein’s Children (Lost Horse, 2018). Five books are forthcoming including Plurality and the Poetics of Self (Palgrave). Presently he is a Regents Professor of English at the University of North Texas.

Lyn Lifshin

My Father Tells Us About Leaving Vilnius

On the night we left Vilnius, I had to bring goats

next door in the moon. Since I was not the youngest, I

couldn’t wait pressed under a shawl of coarse cotton

close to Mama’s breast as she whispered “hurry” in Yiddish.

Her ankles were swollen from ten babies. Though she was

only thirty her waist was thick, her lank hair hung in

strings under the babushka she swore she would burn

in New York City. She dreamt others pointed and snickered

near the tenement, that a neighbor borrowed the only bowl

she brought that was her mother’s and broke it. That night

every move had to be secret. In rooms there was no heat in,

no one put on muddy shoes or talked. It was forbidden to leave,

a law we broke like the skin of ice on pails of milk. Years from

then a daughter would write that I didn’t have a word for

America yet, that night of a new moon. Mother pressed my

brother to her, warned everyone even the babies must not make

a sound. Frozen branches creaked. I shivered at men with

guns near straw roofs on fire. It took our old samovar, every

coin to bribe someone to take us to the train. “Pretend to be

sleeping,” father whispered as the conductor moved near. Mother

stuffed cotton in the baby’s mouth. She held the mortar and

pestle wrapped in my quilt of feathers closer, told me I would

sleep in this soft blue in the years ahead. But that night I

was knocked sideways into ribs of the boat so sea sick I

couldn’t swallow the orange someone threw from an upstairs

bunk tho it was bright as sun and smelled of a new country I

could only imagine though never how my mother would become

a stranger to herself there, forget why we risked dogs and guns to come

LYN LIFSHIN is arguably the most prolific poet of her generation publishing over 130 books and chapbook. Lifshin published her prize winning book about the short lived beautiful race horse Ruffian, The Licorice Daughter: My Year With Ruffian and Barbaro: Beyond Brokenness. Recent books include Ballroom, All the Poets Who Have Touched Me, Living and Dead. All True, Especially The Lies, Light At the End: The Jesus Poems. NYQ books published A Girl Goes into The Woods. An update to her Gale Research Autobiography is out: Lips, Blues, Blue Lace: On The Outside. Forthcoming: Degas Little Dancer and Winter Poems from Kind of a Hurricane Press, Paintings and Poems, from Tangerine Press . Visit her at :www.lynlifshin.com

On the night we left Vilnius, I had to bring goats

next door in the moon. Since I was not the youngest, I

couldn’t wait pressed under a shawl of coarse cotton

close to Mama’s breast as she whispered “hurry” in Yiddish.

Her ankles were swollen from ten babies. Though she was

only thirty her waist was thick, her lank hair hung in

strings under the babushka she swore she would burn

in New York City. She dreamt others pointed and snickered

near the tenement, that a neighbor borrowed the only bowl

she brought that was her mother’s and broke it. That night

every move had to be secret. In rooms there was no heat in,

no one put on muddy shoes or talked. It was forbidden to leave,

a law we broke like the skin of ice on pails of milk. Years from

then a daughter would write that I didn’t have a word for

America yet, that night of a new moon. Mother pressed my

brother to her, warned everyone even the babies must not make

a sound. Frozen branches creaked. I shivered at men with

guns near straw roofs on fire. It took our old samovar, every

coin to bribe someone to take us to the train. “Pretend to be

sleeping,” father whispered as the conductor moved near. Mother

stuffed cotton in the baby’s mouth. She held the mortar and

pestle wrapped in my quilt of feathers closer, told me I would

sleep in this soft blue in the years ahead. But that night I

was knocked sideways into ribs of the boat so sea sick I

couldn’t swallow the orange someone threw from an upstairs

bunk tho it was bright as sun and smelled of a new country I

could only imagine though never how my mother would become

a stranger to herself there, forget why we risked dogs and guns to come

LYN LIFSHIN is arguably the most prolific poet of her generation publishing over 130 books and chapbook. Lifshin published her prize winning book about the short lived beautiful race horse Ruffian, The Licorice Daughter: My Year With Ruffian and Barbaro: Beyond Brokenness. Recent books include Ballroom, All the Poets Who Have Touched Me, Living and Dead. All True, Especially The Lies, Light At the End: The Jesus Poems. NYQ books published A Girl Goes into The Woods. An update to her Gale Research Autobiography is out: Lips, Blues, Blue Lace: On The Outside. Forthcoming: Degas Little Dancer and Winter Poems from Kind of a Hurricane Press, Paintings and Poems, from Tangerine Press . Visit her at :www.lynlifshin.com

Catherine Mazodier

Listening in

Late April, early morning, cold but bright.

I sit outside in a waterfall of birds.

A stranger, I can only make out the obvious dove drawling away

and the semi-colon of a cuckoo in the distance.

The rest is a stream of intertwining chitchat

my father could easily disentangle,

the way I can tell, in the metro in Paris,

who's warbling in Polish, Farsi or Portuguese

though the actual words escape my grasp.

Late April, early morning, cold but bright.

I sit outside in a waterfall of birds.

A stranger, I can only make out the obvious dove drawling away

and the semi-colon of a cuckoo in the distance.

The rest is a stream of intertwining chitchat

my father could easily disentangle,

the way I can tell, in the metro in Paris,

who's warbling in Polish, Farsi or Portuguese

though the actual words escape my grasp.

vie nocturne

Une chauve-souris est entrée dans la chambre.

Son vol, même dans la panique,

éclabousse de silence la nuit

qui tremble de grillons.

J'éteins la lumière électrique

et elle retrouve la fenêtre.

L'orange amère de Mars, visible à l'oeil nu,

ne cligne pas dans son orbite.

Je regarde le ciel qui s'allume par paliers

du toit au tilleul, des crêtes au peuplier.

La fontaine poursuit son obscur soliloque

insensible au frisson des moustiques.

Une chauve-souris est entrée dans la chambre.

Son vol, même dans la panique,

éclabousse de silence la nuit

qui tremble de grillons.

J'éteins la lumière électrique

et elle retrouve la fenêtre.

L'orange amère de Mars, visible à l'oeil nu,

ne cligne pas dans son orbite.

Je regarde le ciel qui s'allume par paliers

du toit au tilleul, des crêtes au peuplier.

La fontaine poursuit son obscur soliloque

insensible au frisson des moustiques.

Nightlife (translated by Catherine Mazodier)

A bat has flown into the bedroom.

Even in panic, the flutter of wings

splashes the cricket-crackling night

with silence.

I switch off the electric lights

and it finds its way out the window.

You can see Mars with the naked eye,

a bitter orange unblinking in its orbit.

I watch as the sky lights up in stages,

roof to lime tree, ridge to poplar.

The fountain's obscure soliloquy goes on,

unruffled by the sizzle of mosquitoes.

Catherine Mazodier teaches linguistics and translation at the university in Paris. She has had poems published in the online supplement to the British poetry journal Agenda, and also published two chapbooks of poems in French and English with a DIY publisher in France (Studio de l'Anaphore), and a few short stories in a now defunct French literary journal called Minimum Rock n Roll.

Tim Kahl 2 poems

Renunciation

It seems I've planned a rape in my dream.

At first it was innocent; I hired a man to

make love to a disabled woman amid

the fluffy bubbles in her tub. The moans

that arose in her tiled enclosure

made it seem like a public service for

the shut-in. But when I returned to the scene,

I saw the stab wounds. I'd been negligent

in my oversight. It was then I awoke.

I told myself I was the victim of too many

bad movies written by men pressing to pay

the bills. They pour on the drama to make

the sale. I'm left to sleep with the overkill.

The next night I'm responsible for the death

of a child, a shark attack at the aquatic center

right beneath the giant water slide.

I refused to act. The whole scene unfolded

like it was on screen. I wanted to know

Where the hell is the life guard? But it was me.

Damn the headlines and their insinuations,

their crude hints that if I'd been elsewhere

I might have intervened. I might have issued

a sharp warning to the actors to forget their lines,

their part in the play, to let the day wind down

into the forgivable, the merciful, the kind.

But I'm a little so-and-so survivor whose

interests are kept intact in mind instead of

letting tragedy draw near and dig itself in.

My sins of omission originate in my dreams

the way Christ's did when he sleepwalked

through Gethsemane in agony. No one can

tell me he stayed awake that entire night in

the garden. No one can tell me dream isn't

a form of meditation either, but the only reason

I dream is for the moral exercise that I renounce

some point later. I have forsaken the great and

wakeful world in all its splendid danger,

and for that, my punishment shall be to sleep,

the sleep of a contaminated soldier.

Hear Tim Kahl read this poem accompanied by music here: Renunciation

It seems I've planned a rape in my dream.

At first it was innocent; I hired a man to

make love to a disabled woman amid

the fluffy bubbles in her tub. The moans

that arose in her tiled enclosure

made it seem like a public service for

the shut-in. But when I returned to the scene,

I saw the stab wounds. I'd been negligent

in my oversight. It was then I awoke.

I told myself I was the victim of too many

bad movies written by men pressing to pay

the bills. They pour on the drama to make

the sale. I'm left to sleep with the overkill.

The next night I'm responsible for the death

of a child, a shark attack at the aquatic center

right beneath the giant water slide.

I refused to act. The whole scene unfolded

like it was on screen. I wanted to know

Where the hell is the life guard? But it was me.

Damn the headlines and their insinuations,

their crude hints that if I'd been elsewhere

I might have intervened. I might have issued

a sharp warning to the actors to forget their lines,

their part in the play, to let the day wind down

into the forgivable, the merciful, the kind.

But I'm a little so-and-so survivor whose

interests are kept intact in mind instead of

letting tragedy draw near and dig itself in.

My sins of omission originate in my dreams

the way Christ's did when he sleepwalked

through Gethsemane in agony. No one can

tell me he stayed awake that entire night in

the garden. No one can tell me dream isn't

a form of meditation either, but the only reason

I dream is for the moral exercise that I renounce

some point later. I have forsaken the great and

wakeful world in all its splendid danger,

and for that, my punishment shall be to sleep,

the sleep of a contaminated soldier.

Hear Tim Kahl read this poem accompanied by music here: Renunciation

On the Cancellation of As The World Turns

Standing behind the ironing board, sawing on the blouse

she got for Christmas, my mom listened to Aida

walled in with Radames right up to the end.

But at noon the tube came on and the world

according to Procter & Gamble unfolded in neat

one hour segments. Dr. Bob and the Oakdale gang

delivered their version of daytime drama in

sweater vests and sweeping neckline dresses.

My mom educated me on the concepts of ratfink

and schnook, which she assured me could

hold over from several seasons ago.

But we’d disagree on some characters,

especially the ever-tactful Dr. Bob, who seemed

a little dull and stuffy to me, the kind of guy

whose wardrobe you wouldn’t want

even if you won it in a giveaway.

His kids fell in love with all the right people

which wasn’t hard in a town full of

beautiful ones, so beautiful they irritated

the soul more than a little. They got on

with the elite and never took their cars into

the garage with the mechanic who has

no English but for twenty bucks will

recharge your A/C. Their lives were as

clear as the Ivory Snow each episode

was brought to you by. My life was a blend

of chores and minor curiosities

that would make a Sunday crawl

to the point of making you look forward to

some momentous day when one choice

would change your fate forever,

or at least as long as it took the writers

to introduce a new character.

Ah, the plenitude of agendas, the passions

ripe enough to split the skin and ooze into

the seat next to you in the living room --

you made me scheme for a secret escape from

the comforts I was given. Oh, life, if only you

had moved at the speed of plot and introduced me

to supercouples with unflagging smiles

and a talent for tossing verbal bonbons to

each other. If only you had rigged

a lingering gaze in perfect silence to explode

into unmanageable kisses. If only you had

engineered a double-cross so diabolical,

it would have brought me to consider a wave

of gunplay. These I had to glean from afternoons

spent with the world turning at an excruciating pace,

with my mother pondering her past in Davenport, Iowa,

a graduate of the high school there and no more,

thinking of the man who ended up a newscaster,

whom she didn’t steal away with into that

forbidden place in the night. Instead, there she was

with me, dusting all the furniture.

Now her program is gone, the one she referred

to as though she alone possessed it.

It has passed into the vapor as has Gregory Peck,

her rock-steady favorite, Mr. Reliable,

the last bastion of fair play and insufferable goodness

seemingly hatched out of a Midwestern town surrounded

by cornfields. Oakdale, Illinois, you were the place

to loiter in my youth when I needed respite from

the metaphysical questions I was battling --

why the universe cannot unstir itself, why

the sun insists on bombarding my retina,

why the moon looks down with its solitary face

as the world turns right next to it. Yes, as the world

is turning, people who watch obsolete shows

will themselves become obsolete. My mother

has flown up into a heaven of reruns to be replaced

by other mothers retooled with their new and

improved purposes, only a few of them staying home

to watch the soaps, slowly walled into their crypts.

So, mom, if you could put down that remote for

a minute and help me Lemon Pledge this desk here

with the dust from some flamboyant star collecting

on it, I’d appreciate it. Already its surface has suffered

too much from a decade’s worth of optical mouse abuse.

Together we could browse your program’s site

and reflect on fifty years of illicit embrace, of firm

clasping in wonderful light, of close-ups on

the great bosomy clutch, and you would be there

once again to tell me the good guys from the schnooks.

From that, my moral barometer would be reset,

ready for service in the wider world of losses

and acquisitions. It is this world that drifts across

my footprints all these years I’ve been traveling

out of my comfort zone. Goodbye, my privileged trips

to see the gorillas. Goodbye, my favorite potato chips,

my hot baths at night, my wishful thinking about

the universe’s decisions. Goodbye, my comfortable

afternoons in Oakdale spent second-guessing the glands

of its beautiful people. Tell me, what is the point of

all this comfort, if it never goes away?

Hear Tim Kahl read this poem accompanied by music here: On the Cancellation of As the World Turns

Tim Kahl [http://www.timkahl.com] is the author of Possessing Yourself (CW Books, 2009), The Century of Travel (CW Books, 2012) The String of Islands (Dink, 2015) and Omnishambles (Bald Trickster, 2019). His work has been published in Prairie Schooner, Drunken Boat, Mad Hatters' Review, Indiana Review, Metazen, Ninth Letter, Sein und Werden, Notre Dame Review, The Really System, Konundrum Engine Literary Magazine, The Journal, The Volta, Parthenon West Review, Caliban and many other journals in the U.S. He is also editor of Clade Song [http://www.cladesong.com]. He is the vice president and events coordinator of The Sacramento Poetry Center. He also has a public installation in Sacramento {In Scarcity We Bare The Teeth}. He plays flutes, guitars, ukuleles, charangos and cavaquinhos. He currently teaches at California State University, Sacramento, where he sings lieder while walking on campus between classes.

Standing behind the ironing board, sawing on the blouse

she got for Christmas, my mom listened to Aida

walled in with Radames right up to the end.

But at noon the tube came on and the world

according to Procter & Gamble unfolded in neat

one hour segments. Dr. Bob and the Oakdale gang

delivered their version of daytime drama in

sweater vests and sweeping neckline dresses.

My mom educated me on the concepts of ratfink

and schnook, which she assured me could

hold over from several seasons ago.

But we’d disagree on some characters,

especially the ever-tactful Dr. Bob, who seemed

a little dull and stuffy to me, the kind of guy

whose wardrobe you wouldn’t want

even if you won it in a giveaway.

His kids fell in love with all the right people

which wasn’t hard in a town full of

beautiful ones, so beautiful they irritated

the soul more than a little. They got on

with the elite and never took their cars into

the garage with the mechanic who has

no English but for twenty bucks will

recharge your A/C. Their lives were as

clear as the Ivory Snow each episode

was brought to you by. My life was a blend

of chores and minor curiosities

that would make a Sunday crawl

to the point of making you look forward to

some momentous day when one choice

would change your fate forever,

or at least as long as it took the writers

to introduce a new character.

Ah, the plenitude of agendas, the passions

ripe enough to split the skin and ooze into

the seat next to you in the living room --

you made me scheme for a secret escape from

the comforts I was given. Oh, life, if only you

had moved at the speed of plot and introduced me

to supercouples with unflagging smiles

and a talent for tossing verbal bonbons to

each other. If only you had rigged

a lingering gaze in perfect silence to explode

into unmanageable kisses. If only you had

engineered a double-cross so diabolical,

it would have brought me to consider a wave

of gunplay. These I had to glean from afternoons

spent with the world turning at an excruciating pace,

with my mother pondering her past in Davenport, Iowa,

a graduate of the high school there and no more,

thinking of the man who ended up a newscaster,

whom she didn’t steal away with into that

forbidden place in the night. Instead, there she was

with me, dusting all the furniture.

Now her program is gone, the one she referred

to as though she alone possessed it.

It has passed into the vapor as has Gregory Peck,

her rock-steady favorite, Mr. Reliable,

the last bastion of fair play and insufferable goodness

seemingly hatched out of a Midwestern town surrounded

by cornfields. Oakdale, Illinois, you were the place

to loiter in my youth when I needed respite from

the metaphysical questions I was battling --

why the universe cannot unstir itself, why

the sun insists on bombarding my retina,

why the moon looks down with its solitary face

as the world turns right next to it. Yes, as the world

is turning, people who watch obsolete shows

will themselves become obsolete. My mother

has flown up into a heaven of reruns to be replaced

by other mothers retooled with their new and

improved purposes, only a few of them staying home

to watch the soaps, slowly walled into their crypts.

So, mom, if you could put down that remote for

a minute and help me Lemon Pledge this desk here

with the dust from some flamboyant star collecting

on it, I’d appreciate it. Already its surface has suffered

too much from a decade’s worth of optical mouse abuse.

Together we could browse your program’s site

and reflect on fifty years of illicit embrace, of firm

clasping in wonderful light, of close-ups on

the great bosomy clutch, and you would be there

once again to tell me the good guys from the schnooks.

From that, my moral barometer would be reset,

ready for service in the wider world of losses

and acquisitions. It is this world that drifts across

my footprints all these years I’ve been traveling

out of my comfort zone. Goodbye, my privileged trips

to see the gorillas. Goodbye, my favorite potato chips,

my hot baths at night, my wishful thinking about

the universe’s decisions. Goodbye, my comfortable

afternoons in Oakdale spent second-guessing the glands

of its beautiful people. Tell me, what is the point of

all this comfort, if it never goes away?

Hear Tim Kahl read this poem accompanied by music here: On the Cancellation of As the World Turns

Tim Kahl [http://www.timkahl.com] is the author of Possessing Yourself (CW Books, 2009), The Century of Travel (CW Books, 2012) The String of Islands (Dink, 2015) and Omnishambles (Bald Trickster, 2019). His work has been published in Prairie Schooner, Drunken Boat, Mad Hatters' Review, Indiana Review, Metazen, Ninth Letter, Sein und Werden, Notre Dame Review, The Really System, Konundrum Engine Literary Magazine, The Journal, The Volta, Parthenon West Review, Caliban and many other journals in the U.S. He is also editor of Clade Song [http://www.cladesong.com]. He is the vice president and events coordinator of The Sacramento Poetry Center. He also has a public installation in Sacramento {In Scarcity We Bare The Teeth}. He plays flutes, guitars, ukuleles, charangos and cavaquinhos. He currently teaches at California State University, Sacramento, where he sings lieder while walking on campus between classes.

Kushal Poddar 2 poems

Everyone's Gone to The Moon, Nina Simone

For two inept hours we stretch our love

hurting each other (not what

you think—her head hits mine,

my knee DUIs between her long legs).

Saturday street drapes outside.

Everyone else has gone to the paper moon.

Radio croons a moony uh-la-la-la.

Everyone else has gone. They wrote in

the newspaper—an asteroid will pass this planet.

You comb your hair. I read the rest of the news.

On the porcelain the half eaten cookie gathers a fly.

Everyone else has gone to the moon.

For two inept hours we stretch our love

hurting each other (not what

you think—her head hits mine,

my knee DUIs between her long legs).

Saturday street drapes outside.

Everyone else has gone to the paper moon.

Radio croons a moony uh-la-la-la.

Everyone else has gone. They wrote in

the newspaper—an asteroid will pass this planet.

You comb your hair. I read the rest of the news.

On the porcelain the half eaten cookie gathers a fly.

Everyone else has gone to the moon.

God Complex

My therapist says, she needs my father

on her battered counseling couch

for my therapeutics.

She tells my father after a session

with him, she needs his father

for an analysis.

Father cites, he rests in peace.

Doesn’t matter, insists my therapist,

I just need his id.

Months later, lying on the couch

God reveals his impairments

in the areas of foreseeing.

There, says my therapist,

your cure heals its wound blindly.

Kushal Poddar is author of The Circus Came To My Island, A Place For Your Ghost Animals, Understanding The Neighborhood, Scratches Within, Kleptomaniac's Book of Unoriginal Poems, Eternity Restoration Project- Selected and New Poems and most recently, Herding My Thoughts To The Slaughterhouse-A Prequel (Alien Buddha Press).

My therapist says, she needs my father

on her battered counseling couch

for my therapeutics.

She tells my father after a session

with him, she needs his father

for an analysis.

Father cites, he rests in peace.

Doesn’t matter, insists my therapist,

I just need his id.

Months later, lying on the couch

God reveals his impairments

in the areas of foreseeing.

There, says my therapist,

your cure heals its wound blindly.

Kushal Poddar is author of The Circus Came To My Island, A Place For Your Ghost Animals, Understanding The Neighborhood, Scratches Within, Kleptomaniac's Book of Unoriginal Poems, Eternity Restoration Project- Selected and New Poems and most recently, Herding My Thoughts To The Slaughterhouse-A Prequel (Alien Buddha Press).

Laura Ohlmann 3 poems

For My Father

After Sharon Olds

You were my first child.

I took you in my arms after the first

attempted hanging to your bedpost,

hid the used Home Depot rope

in my closet and covered it like dead prey.

At the hospital I washed your hands

with foamed sanitizer, cleaned

your blood crusted lips with a wet wipe—

your legs cuffed by pressure monitors—too weak

and swollen to lift you anyway.

How did we get to this moment?

I stood with you by Mom’s grave at 12, watched

the curators lower her pine casket towards

the rocking earth—my body bowing towards it--

like in your waterbed that evening,

and I grasped your hand in mine. My child face

saw your softened face and sensed

a splitting chasm there.

You weren’t much of a father—but you loved. You saved

what you could and kept it beside you,

like the paper towel rolls strung together

and pop tabs that gather around the house.

Maybe it’s my fault that you want me in your bed

each night, beside your clumsy breath,

the CPAP soon to follow.

I stayed beside you, a child mannequin, enabler,

companion, daughter-wife,

holding your puttied hand in mine.

After Sharon Olds

You were my first child.

I took you in my arms after the first

attempted hanging to your bedpost,

hid the used Home Depot rope

in my closet and covered it like dead prey.

At the hospital I washed your hands

with foamed sanitizer, cleaned

your blood crusted lips with a wet wipe—

your legs cuffed by pressure monitors—too weak

and swollen to lift you anyway.

How did we get to this moment?

I stood with you by Mom’s grave at 12, watched

the curators lower her pine casket towards

the rocking earth—my body bowing towards it--

like in your waterbed that evening,

and I grasped your hand in mine. My child face

saw your softened face and sensed

a splitting chasm there.

You weren’t much of a father—but you loved. You saved

what you could and kept it beside you,

like the paper towel rolls strung together

and pop tabs that gather around the house.

Maybe it’s my fault that you want me in your bed

each night, beside your clumsy breath,

the CPAP soon to follow.

I stayed beside you, a child mannequin, enabler,

companion, daughter-wife,

holding your puttied hand in mine.

The Altar

An altar of red rock rises before us.

Fremont cottonwoods lay rows

down the slick black gravel

like a bed of white rose petals.

We’ve seen it all before. Even the black

figurine of a bear laying in the sand.

I dust its coat with my fingertips,

now coated in red earth and whisper

a prayer into the fingernail sized muzzle.

Utah Juniper’s decorate the street corners

and I see the bouquet from my dreams-

nucleus of each black center like a fetus’

face rising towards my face, while fetal pine cones

hang like corpses above our heads.

An altar of red rock rises before us.

Fremont cottonwoods lay rows

down the slick black gravel

like a bed of white rose petals.

We’ve seen it all before. Even the black

figurine of a bear laying in the sand.

I dust its coat with my fingertips,

now coated in red earth and whisper

a prayer into the fingernail sized muzzle.

Utah Juniper’s decorate the street corners

and I see the bouquet from my dreams-

nucleus of each black center like a fetus’

face rising towards my face, while fetal pine cones

hang like corpses above our heads.

To Justin

Remember my childhood swing set? Your body spearheading mine,

rocking me back & forth with your hips. What was that feeling?

Was it love that tucked itself, like a hummingbird between my legs?

You leaned in for the first kiss & I imagined being struck by lightning &

foot flying into the air. Too soon, you asked me to your house, where

no one would be home.

I had never kissed a man or

held a hand or

a wrist or

a neck or

soft shoulders & mountaincrest of vertebrae.

You untucked me from your truck and led me to your bedroom, where bottles

of liquor lined your bookshelves. You stripped the cheap bra from the shoulders

and left the collarbones with a slug-trail of sputum. I didn’t want sex--

yet you submerged your fingers between the lips & asked

if you could go in—your penis bobbing from the zipper of your pants,

while I lay in skin & shame before you. No, I told you.

So you kissed the trailbone neck and furry-stream along the baby-fat stomach.

Can I go in? I want you so bad, you told me. I wasn’t used to saying no to men.

Can I slip in the back? Your hand slapped the ass, the body already positioned

over the apex of the bed. You made circles over the asscheeks.

I’ll give you a spanking. Your cockular tip at the anus now, testing the entrance -

no saliva or lube to place it.

Okay, I told you & felt shame slip into the asshole.

When you dropped me off & I submerged the empty birdcage body into the tub,

your fluid leaked from it & bruises gripped the hip bones & I wondered

what it meant for a man to love me.

Laura Ohlmann’s poetry and nonfiction has appeared in Cake, the 2016 Wild Ekphrastic Contest, and Honey & Lime. She was born in Cooper City, Florida and is currently an MFA student at the University of Central Florida. She resides in Orlando with her dog, Lady and her human, Jon.

Remember my childhood swing set? Your body spearheading mine,

rocking me back & forth with your hips. What was that feeling?

Was it love that tucked itself, like a hummingbird between my legs?

You leaned in for the first kiss & I imagined being struck by lightning &

foot flying into the air. Too soon, you asked me to your house, where

no one would be home.

I had never kissed a man or

held a hand or

a wrist or

a neck or

soft shoulders & mountaincrest of vertebrae.

You untucked me from your truck and led me to your bedroom, where bottles

of liquor lined your bookshelves. You stripped the cheap bra from the shoulders

and left the collarbones with a slug-trail of sputum. I didn’t want sex--

yet you submerged your fingers between the lips & asked

if you could go in—your penis bobbing from the zipper of your pants,

while I lay in skin & shame before you. No, I told you.

So you kissed the trailbone neck and furry-stream along the baby-fat stomach.

Can I go in? I want you so bad, you told me. I wasn’t used to saying no to men.

Can I slip in the back? Your hand slapped the ass, the body already positioned

over the apex of the bed. You made circles over the asscheeks.

I’ll give you a spanking. Your cockular tip at the anus now, testing the entrance -

no saliva or lube to place it.

Okay, I told you & felt shame slip into the asshole.

When you dropped me off & I submerged the empty birdcage body into the tub,

your fluid leaked from it & bruises gripped the hip bones & I wondered

what it meant for a man to love me.

Laura Ohlmann’s poetry and nonfiction has appeared in Cake, the 2016 Wild Ekphrastic Contest, and Honey & Lime. She was born in Cooper City, Florida and is currently an MFA student at the University of Central Florida. She resides in Orlando with her dog, Lady and her human, Jon.

Keith Ratzlaff 3 poems

After

Because I’ve let the apples

fall, mowed around their

constellations in the grass.

This year fire blight

kept us from pruning;

last year it was negligence

and forgetting, two sides

of the same ignorance.

So ironically this year,

the trees cascade apples,

and now I have them

in spades and bushels

I’ve carried to the compost bin

as of no worth. And the yard

smells of vinegar and the wasps

are drunk on the cider, and

the apples look better blighted

than the rest of the garden--

beetled, wilted—better than

the waterlogged pine

coughing up a thousand cones

before it flames out. Because

at first, I mowed over the apples,

but their trepanned heads made

the yard some sort of battlefield.

So now instead I let them fall,

make their small zodiacs

in the earth-bound heavens.

Yesterday my horoscope said,

“Leo, endings may be challenging

for you now.” But I don’t need

stars telling me the future:

Next week the last hostas

will raise their lavender antennae;

then blackened coneflowers,

the final sweet peppers. After that,

frost we’ll save the tomatoes from--

only for a night or two—by covering them

with sheets we used to sleep under.

Because I’ve let the apples

fall, mowed around their

constellations in the grass.

This year fire blight

kept us from pruning;

last year it was negligence

and forgetting, two sides

of the same ignorance.

So ironically this year,

the trees cascade apples,

and now I have them

in spades and bushels

I’ve carried to the compost bin

as of no worth. And the yard

smells of vinegar and the wasps

are drunk on the cider, and

the apples look better blighted

than the rest of the garden--

beetled, wilted—better than

the waterlogged pine

coughing up a thousand cones

before it flames out. Because

at first, I mowed over the apples,

but their trepanned heads made

the yard some sort of battlefield.

So now instead I let them fall,

make their small zodiacs

in the earth-bound heavens.

Yesterday my horoscope said,

“Leo, endings may be challenging

for you now.” But I don’t need

stars telling me the future:

Next week the last hostas

will raise their lavender antennae;

then blackened coneflowers,

the final sweet peppers. After that,

frost we’ll save the tomatoes from--

only for a night or two—by covering them

with sheets we used to sleep under.

Sitting Above a Ravine in Lynchburg, Virginia

I’m perched on the edge

because of flowers.

Because the almost

dramatic drop-off

gives me a pleasant vertigo.

And I’m writing a poem

imagining how I’d die

if I flung myself

over the edge,

a martyr for spring.

But I wouldn’t--

die, I mean—not with

the crows’ thick caw,

the rain-softened ground

waiting to catch me.

I’ve got a red magnolia leaf

for company,

and a tiny cedar cone,

and the almost

gray-green of a holly leaf

with its almost dangerous blade.

And March is ruining

the dun-colored

leaves with violets.

Who asked them back?

How can I fling myself

almost to my death in a poem

when there are violets,

and strawberries, a bee

broken from the tomb,

the small blue eyes

of spring beauties at the bottom?

How, with flowers everywhere,

can I concentrate

instead on being

last year’s magnolia leaf--

bruised over half my body,

stippled with white fungus--

with just a little green

to show who I was,

and just a little red

to show how much

I loved the glossy world once?

How can I die

in the plane crash I imagined

last night on the flight

from Charlottesville--

the scuffed turbo-prop

that lurched and bucked

and wanted, I was sure,

to throw itself down now, now,

into some Blue Ridge ravine?

Because what’s the use

if you’re a plane,

old and wheezing,

carrying college students

back from break--

who are not afraid

and can’t imagine dying--

and carrying one old poet

who is and can and who

could name the flowers

they would crash into?

What’s the use

if you’re a plane running

the midnight commute

to Lynchburg again and over,

when all they’ll do someday

is push you into the ravine

like the lawnmower you are?

But we didn’t crash

and everyone’s in class,

and I’m alive and watching

spring resurrect itself

into violets and trout lilies,

watching thunderheads

bunch above Lynchburg

where I landed last night,

so happy and thirsty

for the ground I licked

rain off my windshield

and said thank you.

I’m perched on the edge

because of flowers.

Because the almost

dramatic drop-off

gives me a pleasant vertigo.

And I’m writing a poem

imagining how I’d die

if I flung myself

over the edge,

a martyr for spring.

But I wouldn’t--

die, I mean—not with

the crows’ thick caw,

the rain-softened ground

waiting to catch me.

I’ve got a red magnolia leaf

for company,

and a tiny cedar cone,

and the almost

gray-green of a holly leaf

with its almost dangerous blade.

And March is ruining

the dun-colored

leaves with violets.

Who asked them back?

How can I fling myself

almost to my death in a poem

when there are violets,

and strawberries, a bee

broken from the tomb,

the small blue eyes

of spring beauties at the bottom?

How, with flowers everywhere,

can I concentrate

instead on being

last year’s magnolia leaf--

bruised over half my body,

stippled with white fungus--

with just a little green

to show who I was,

and just a little red

to show how much

I loved the glossy world once?

How can I die

in the plane crash I imagined

last night on the flight

from Charlottesville--

the scuffed turbo-prop

that lurched and bucked

and wanted, I was sure,

to throw itself down now, now,

into some Blue Ridge ravine?

Because what’s the use

if you’re a plane,

old and wheezing,

carrying college students

back from break--

who are not afraid

and can’t imagine dying--

and carrying one old poet

who is and can and who

could name the flowers

they would crash into?

What’s the use

if you’re a plane running

the midnight commute

to Lynchburg again and over,

when all they’ll do someday

is push you into the ravine

like the lawnmower you are?

But we didn’t crash

and everyone’s in class,

and I’m alive and watching

spring resurrect itself

into violets and trout lilies,

watching thunderheads

bunch above Lynchburg

where I landed last night,

so happy and thirsty

for the ground I licked

rain off my windshield

and said thank you.

The Couple in Valentine Costumes

Let’s not talk about them,

the couple we envied

at the party—James and Margaret?--

wearing cupids in their hair,

and big sandwich-sign hearts

draped over their shoulders

like billboards for love.

Valentine hearts resemble

nothing but themselves--

not the pipes and vaults

of any actual organs.

And in valentine hearts

there are no echoes of

the real heart’s iambic la dah,

predictable as polka drumming;

no orchestras there,

or the shush of brushes,

no cymbals, no tom-toms,

no playing around with the offbeat

(though offbeats are what we love--

what James and Margaret loved—

dancing like romantic red paddles,

gawky and spinning to some samba

that would kill a real heart).

Someone has opened a window,

and music is floating

into the streetlights, then up

into the routes the Concorde

used to fly above us before

everything went tragic.

Then the moon, then

the constellations

living their dot to dot lives:

the virgin Pleiades chased

forever by Orion chased

forever by the scorpion;

Cassiopeia stuffed in a basket

and hung upside down

for boasting she was

more beautiful than even the gods.

I don't know

if James and Margaret

were in love or not;

there are no hearts

in the stars, no shapes

there to auger love for them.

Only dogs and ravens,

doves and bears;

only Boötes the plowman

courting the enigmatic Norma,

bent like a carpenter’s square;

only the leftover story

of Andromeda, Cassiopeia’s

truly beautiful daughter

set in the heavens

for being true to Perseus,

who dances with her

forever—contiguously—

the kind of almost touching

that passes for love among stars.

In twenty-five years

we’ve never gone dancing;

probably not tonight, either.

That’s not our story.

Think instead of the night

we parked in a field

east of town to watch the eclipse.

The moon was a peach,

an old pond-glimmerer,

her spin and step so certain

she let the sun—that old dazzler--

put the moves on,

let Earth cut in, then

let the sun win her back

through all her phases--

new, wan, gibbous, full.

Sol and Luna,

the big lights so finely matched

they disappear into each other’s arms.

Or think of us as us—

me the salesman’s mild-mannered son;

you more beautiful than even the stars.

Keith and Treva,

about whom there are stories

too numerous to tell:

Keith Ratzlaff’s most recent books of poetry are Then, A Thousand Crows (Anhinga Press, 2009) and Dubious Angels: Poems after Paul Klee (Anhinga, 2005). His latest book, Who’s Asking?, is forthcoming, also from Anhinga. Poems and reviews have appeared recently in The Cincinnati Review, The Georgia Review, Arts and Letters, Colorado Review, and The American Reader. His awards include the Anhinga Prize for Poetry, the Theodore Roethke Award, two Pushcart Prizes and inclusion in The Best American Poetry 2009.

Paul Dickey 2 poems

The Violence Poetry Could Speak of Today in America

A book thief recently stole a signed first-edition copy of Billy Collins'

Nine Horses and blasted it with a .410 shotgun.

– https://www.citizen-times.com/story/news/local/2015/05/21/book-thief-vents-rage-laureates-poetry-shotgun/27711589/

If you know anything of Billy’s poetry,

you know how natural it feels a gun

in your hands, how easy it could have been

to forget to pay for it

before taking it from the bookstore

to meet and greet America.

A signed, pristine first edition, though.

So that was a crime, naturally, but nonetheless,

it apparently traveled well--

expressing itself eloquently but accessibly

on the daily issues—how to survive

while sleeping under a motorcycle seat

on the road to Waco,

or in a backpack in Ferguson, Missouri,

hitching a ride in a police car

in the Bronx or Cleveland

with the cache of weapons, but of course,

it is no crime to have weapons in America.

Only the AK-47’s and the sling blades felt awkward,

in the company of Billy’s poetry.

The rifles and ammunition chatted

amicably with the free verse,

and were overheard collaboratively discussing

the glory and thrills of American history.

But the poetry, I must say,

soon had an experience it will not soon forget,

though it still found its way back home

like a Billy Collins poem,

enlightened by the adventure.

The thin volume, more valuable now

for its trouble, returned to its shelf

snug between Bronte and cummings.

A book thief recently stole a signed first-edition copy of Billy Collins'