SoFloPoJo Contents: Home * Essays * Interviews * Reviews * Special * Video * Visual Arts * Archives * Calendar * Masthead * SUBMIT * Tip Jar

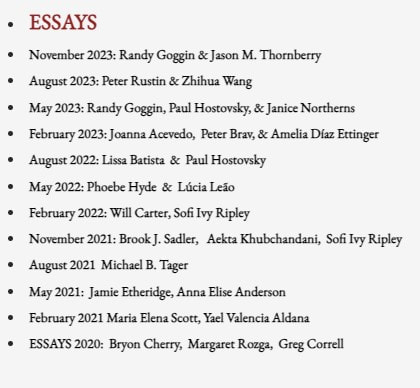

Prior Essays: Essays 2020-2021, Essays 2022-2023

ESSAYS - August 2024

Paul Hostovsky

COMING SOON: Paul's Essay LAST WORDS (8/1/2024)

Paul Hostovsky has won a Pushcart Prize, two Best of the Net Awards, the FutureCycle Poetry Book Prize, and has been featured on Poetry Daily, Verse Daily, The Writer's Almanac, and the Best American Poetry blog. His latest book of poems is PITCHING FOR THE APOSTATES (Kelsay, 2023). He makes his living in Boston as a sign language interpreter.

Website: paulhostovsky.com

Website: paulhostovsky.com

ESSAYS - February 2024

Okbi Han

|

Tenno Heika Banzai

My maternal grandfather is a man who adds jazz and classical music to his iPod Nano. Listening to Rachmaninoff, he cuts up newspaper articles to make a scrapbook. He is a sweet old man who appreciates Frida Kahlo and tells me to become an artist like her, an artist to be remembered even after death. Once he discovered a strange tattoo on his granddaughter’s neck. He thought she loved Vegemil so much that she inscribed it into her body, and he decided to send her a box of Vegemil. The truth, however, is that I am such a big fan of Britney Spears and got a bottle of poison tattooed, not a bottle of soy milk. My grandfather loved his wife so much that he couldn't even set foot at her funeral. He is a war hero of the Korean War, and a burial site is reserved for him at the Memorial Hall in Seoul. After hearing that his wife could not be buried with him there because she had died before him, my grandfather was furious. He was literally jumping around the hall. In his military years, he used to be a trumpeter. His band played for the US Army. My grandfather would send me letters on my birthday and some short English phrases were included in them. I believe his years spent in the US Army base are the reason for those phrases. My grandfather is a Japanese collaborator, though. A few years ago, my whole family gathered for a Chuseok evening out. On the way back, my grandfather declared that he was a Japanese collaborator. My aunt, busy with driving, did not seem to care so much. She simply mumbled something like “yeah, sure” without understanding what he was actually saying. In his loud angry voice, my grandfather again declared that he was a Japanese collaborator. He attended a national people’s school when he was a boy. That was what the elementary school was called when Korea was under the colonial rule of Japan. Every morning at the school, he was forced to cry out “Tenno Heika Banzai!” Long live His Majesty the Emperor. He confessed that he screamed harder and louder than anyone else because he was afraid and did not want to get beaten up by the teachers. Sometimes he would also shout three times in a row, “Banzai! Banzai! Banzai!” My grandfather concluded that there was no way he could be exempt from being a collaborator with such deeds and that he deserved to be purged. “I am no exception. It was never a right action, no?” He asked my aunt and umma in the car. I believe my grandfather wanted to hear back from us that it was not true. I told him that he was not a Japanese collaborator. The reply made in haste, however, did not leave my grandfather relieved. While the whole family went to a café to have coffee and dessert, he went home alone. Splitting a matcha macaron into halves for my nephew, I was still thinking about what my grandfather had said. Maybe I should have told him that a young child does not know anything, and he is unable to do something so bad. On the other hand, I thought there was something farcical about how he remembered his boyhood. Dessert time with a young nephew was not the best occasion to ponder on a colonial memory, nevertheless. The next moment, I was reminded that I prefer matcha from Japan, as Korean ones tend to taste bitter. |

Okbi Han is a poet, painter, and video editor. She lives in Seoul and can be reached at [email protected]. She is also a professional french fries craver.