Issue 11 November 2018

Mary Galvin, Guest Editor

Poets in this issue: Esperanza Snyder Virgil Suárez Kurt Luchs Jesse Millner Sean Sexton Maureen Seaton D. Nurkse Jane Rosenberg LaForge Lola Haskins Jeannie E. Roberts Elizabeth Jacobson Lucia Leao W.T. Pfefferle John L. Stanizzi Heikki Huotari Peycho Panev Judy Kronenfeld Sarah White Stephen Gibson Steve Klepetar Michael Brownstein Ron Reikki Al Maginnes Barry Peters

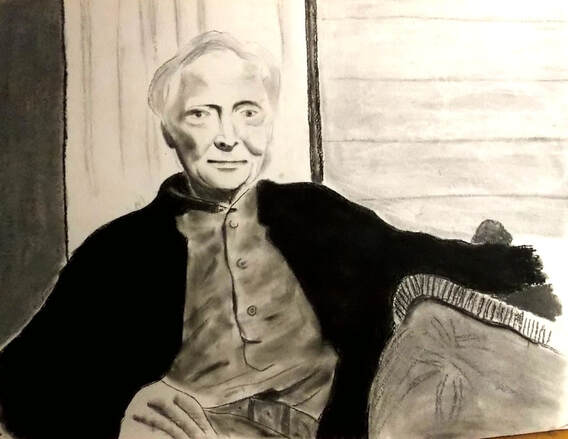

Merwin, charcoal on paper by Michael Byro

Lucia Leao

a kind of marriage

for Oswaldo Martins

the erotic poems were sent to ashes

when he died, but his wife grabbed a few

lower-case beginnings of lines becoming

dust in her eyes, but she didn’t cry

in fictional women he praised her,

and she was happy for him, for that

island of so many lakes, the imagination

she wore with him, his body

Lucia Leao is a translator and writer. Her poems have been published in Chariton Review, SoFloPoJo, and in Brazilian websites dedicated to poetry. Leao has published a collection of short stories and is co-author of a young-adult novel, both published in Portuguese, in Brazil. She has a bachelor’s degree in English and Literatures from Rio de Janeiro State University, Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), a master’s degree in Brazilian Literature from UERJ and a master’s in print journalism from University of Miami. She was born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

for Oswaldo Martins

the erotic poems were sent to ashes

when he died, but his wife grabbed a few

lower-case beginnings of lines becoming

dust in her eyes, but she didn’t cry

in fictional women he praised her,

and she was happy for him, for that

island of so many lakes, the imagination

she wore with him, his body

Lucia Leao is a translator and writer. Her poems have been published in Chariton Review, SoFloPoJo, and in Brazilian websites dedicated to poetry. Leao has published a collection of short stories and is co-author of a young-adult novel, both published in Portuguese, in Brazil. She has a bachelor’s degree in English and Literatures from Rio de Janeiro State University, Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), a master’s degree in Brazilian Literature from UERJ and a master’s in print journalism from University of Miami. She was born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Steve Klepetar

Swimming in the Rain

How you howled when rain

beat down and thunder roared

overhead.

You swore that lightning

crashed into a puddle

by your feet, but

that may have been a vision

or a dream.

I saw a shadow

shiver loose, a shade

of a shade torn apart by wind.

Then we were swimming in a lake

pocked by rain, with black pines

clustered around the shore.

Your mother called and called your name.

Her voice rose out of darkness as you struggled

to breathe, pulling the water toward you with your little arms.

Steve Klepetar lives in the Berkshires in Massachusetts. His work has received several nominations for Best of the Net and the Pushcart Prize. Recent collections include A Landscape in Hell (Flutter Press) and Why Glass Shatters (One Sentence Chaps).

How you howled when rain

beat down and thunder roared

overhead.

You swore that lightning

crashed into a puddle

by your feet, but

that may have been a vision

or a dream.

I saw a shadow

shiver loose, a shade

of a shade torn apart by wind.

Then we were swimming in a lake

pocked by rain, with black pines

clustered around the shore.

Your mother called and called your name.

Her voice rose out of darkness as you struggled

to breathe, pulling the water toward you with your little arms.

Steve Klepetar lives in the Berkshires in Massachusetts. His work has received several nominations for Best of the Net and the Pushcart Prize. Recent collections include A Landscape in Hell (Flutter Press) and Why Glass Shatters (One Sentence Chaps).

Esperanza Snyder 3 poems

Immigrant

Because before I could walk my father took me to the embassy in Bogotá

with my first black and white photograph and his own passport,

I used to say this was the only thing he ever did for me. And the best.

No, he didn’t give me Sunday mornings in church, afternoons in the park,

bedtime stories, Happy Birthday calls, wrapped Christmas presents.

From him, no family dinners, money for clothes, or food, or college.

He wasn’t there when my mother, tired of mothering,

locked me in the closet with a bag full of mangoes--I had eaten

a mango without asking--so I would learn to want less, expect less.

In Bogotá, I’d sit under the dining room table, mouth open,

sugar shaker pouring crystals straight on to my tongue. At fifteen,

not knowing what to do with me, my mother brought me here

to live, to study, and to work, so we could pay the rent. I came to this,

my new adopted country, not through a tunnel, or in an overflowing

boat, not locked in a van, but in an airplane, with a passport.

At fifteen, after school, long after I’d lost my taste for sweets,

I sold chocolates in a candy shop. When I walked home

from work at night, alone, or worse, got a ride from a man, my mother,

always distracted with problems of her own, wouldn’t ask what took

me so long. Because my US Passport was the only thing

my father left, when he left--that, and the empty drawers, empty

bank account, my mother’s empty bed, I held on to the document

and what I thought it meant: that I was loved, that I was

wanted, that I was good enough for him, for them.

Because before I could walk my father took me to the embassy in Bogotá

with my first black and white photograph and his own passport,

I used to say this was the only thing he ever did for me. And the best.

No, he didn’t give me Sunday mornings in church, afternoons in the park,

bedtime stories, Happy Birthday calls, wrapped Christmas presents.

From him, no family dinners, money for clothes, or food, or college.

He wasn’t there when my mother, tired of mothering,

locked me in the closet with a bag full of mangoes--I had eaten

a mango without asking--so I would learn to want less, expect less.

In Bogotá, I’d sit under the dining room table, mouth open,

sugar shaker pouring crystals straight on to my tongue. At fifteen,

not knowing what to do with me, my mother brought me here

to live, to study, and to work, so we could pay the rent. I came to this,

my new adopted country, not through a tunnel, or in an overflowing

boat, not locked in a van, but in an airplane, with a passport.

At fifteen, after school, long after I’d lost my taste for sweets,

I sold chocolates in a candy shop. When I walked home

from work at night, alone, or worse, got a ride from a man, my mother,

always distracted with problems of her own, wouldn’t ask what took

me so long. Because my US Passport was the only thing

my father left, when he left--that, and the empty drawers, empty

bank account, my mother’s empty bed, I held on to the document

and what I thought it meant: that I was loved, that I was

wanted, that I was good enough for him, for them.

Wings

With lines from Jack Gilbert

That May, on the airplane to Milan

my thoughts turned to leaving,

to cutting ties, lies, burning letters.

Flying into Malpensa airport

I flew into a new life, a new love.

Tuscan mornings I opened

windows to a sea of vineyards,

a sweet scent of grapes ripening,

the gentleness in me like deer

standing in the dawn mist.

Summer afternoons I took

my daughter to the pool,

watched her float in arm bands.

Chlorine on our skin, water

all around us, Petrarch’s

cypress trees lining the road,

the Tuscan sky above us,

she learned to swim her first

summer on earth. I dreamed

of giving her wings like Daedalus

gave his son. Who knew Icarus

would plunge into the sea searching

for freedom? Who knew that

after nine Tuscan summers, love

fading out of me, my thoughts

would turn to leaving, to taking

airplanes, a suitcase and a child?

Everyone forgets that Icarus also flew.

With lines from Jack Gilbert

That May, on the airplane to Milan

my thoughts turned to leaving,

to cutting ties, lies, burning letters.

Flying into Malpensa airport

I flew into a new life, a new love.

Tuscan mornings I opened

windows to a sea of vineyards,

a sweet scent of grapes ripening,

the gentleness in me like deer

standing in the dawn mist.

Summer afternoons I took

my daughter to the pool,

watched her float in arm bands.

Chlorine on our skin, water

all around us, Petrarch’s

cypress trees lining the road,

the Tuscan sky above us,

she learned to swim her first

summer on earth. I dreamed

of giving her wings like Daedalus

gave his son. Who knew Icarus

would plunge into the sea searching

for freedom? Who knew that

after nine Tuscan summers, love

fading out of me, my thoughts

would turn to leaving, to taking

airplanes, a suitcase and a child?

Everyone forgets that Icarus also flew.

Waiting

He was there, waiting for me in a big, beat up,

white sedan, in the cold drizzle, waiting for me

to finish selling chocolate covered cherries,

sitting in the dark, waiting for the cash register

to ring, the numbers to match, because our ages

didn’t, waiting for me to turn the key, lock up, hang

up my polyester smock. He waited to drive me home,

winter evenings, around highways, down the road,

to park. Who tied my mother’s tongue, so she

couldn’t, wouldn’t, ask, “What took so long?”

Perhaps, tired after work, she didn’t want to talk.

Years later, I learned about the winter day

he came with roses while I slept on my childhood’s

bed, how she shut the door on him, his flowers.

Esperanza Snyder was born in Colombia and lives in West Virginia. She holds degrees from the College of William and Mary, George Washington, Johns Hopkins, and the University of Manchester. Mother of three children, she is currently the assistant director of the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference in Sicily and poet laureate of Shepherdstown, West Virginia.

He was there, waiting for me in a big, beat up,

white sedan, in the cold drizzle, waiting for me

to finish selling chocolate covered cherries,

sitting in the dark, waiting for the cash register

to ring, the numbers to match, because our ages

didn’t, waiting for me to turn the key, lock up, hang

up my polyester smock. He waited to drive me home,

winter evenings, around highways, down the road,

to park. Who tied my mother’s tongue, so she

couldn’t, wouldn’t, ask, “What took so long?”

Perhaps, tired after work, she didn’t want to talk.

Years later, I learned about the winter day

he came with roses while I slept on my childhood’s

bed, how she shut the door on him, his flowers.

Esperanza Snyder was born in Colombia and lives in West Virginia. She holds degrees from the College of William and Mary, George Washington, Johns Hopkins, and the University of Manchester. Mother of three children, she is currently the assistant director of the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference in Sicily and poet laureate of Shepherdstown, West Virginia.

Virgil Suárez

The Lion Head Belt Buckle

My father bought it for me as a gift in the Madrid rastro

near where we lived, new immigrants from Cuba.

The eyes and mane carved deep into the metal, the tip of the nose

already thin with the blush of wear. My mother found a brown

leather strap and made it into a belt with enough slack and holes

to see me wearing it in Los Angeles where we landed next.

My father worked at Los Dos Toros, a meat market run by Papito,

A heavy-set man with a quick smile and when I would visit

the market after school to wait for my father to bring me home,

Papito always talked to me about baseball and his favorite

Cincinnati Reds players. It was there one of his employees,

a skinny man with deep set eyes and crow-feather black

hair would stop me in the narrow hallway by the produce tables

and grab the belt buckle and praise it. All along passing his hand

over my penis. “You are strong,” he would whisper, “like this lion.”

I would recoil from his touch and move away back to the front

where Papito would ask me about what bases I intended

to play next season on Los Cubanitos team. I never told my father,

or anyone, but the afternoon I showed up and the Fire Department

and police and ambulances huddled in the alleyway behind

Los Dos Toros, I knew something terrible had happened. Some

other kid had uttered the man’s groping and insisting on a kiss

in the almacén, the darkened storage room past the meat locker.

And another father had taken matters into his own hands.

But instead I found my father hosing the back door entrance,

washing the blood down to the alleyway. He told me to wait for him

in the car. The paramedics rolled out Papito, shot and dead on a stretcher,

victim of a hold up. The dark Cuban man who’d felt me up time

and again stood in the shade of a tree weeping and kicking the dirt

with blood encrusted shoes. I found out later he was the one who

slammed the assailant against the wall, and beat him unconscious.

Fuerte como un leon. The words fluttered like cow birds in the back

of my mind. Scattershot and ringing like the violence among the men.

Virgil Suárez is the author a multitude of books about the Cuban-American experience. His most recent collection is The Soviet Circus Comes to Havana & Other Stories. When he is not writing, he is out riding his Yamaha V-Star 1100 Classic up and down the Blue Highways of the Southeastern United States, stopping often enough to take a picture or two of abandoned places.

My father bought it for me as a gift in the Madrid rastro

near where we lived, new immigrants from Cuba.

The eyes and mane carved deep into the metal, the tip of the nose

already thin with the blush of wear. My mother found a brown

leather strap and made it into a belt with enough slack and holes

to see me wearing it in Los Angeles where we landed next.

My father worked at Los Dos Toros, a meat market run by Papito,

A heavy-set man with a quick smile and when I would visit

the market after school to wait for my father to bring me home,

Papito always talked to me about baseball and his favorite

Cincinnati Reds players. It was there one of his employees,

a skinny man with deep set eyes and crow-feather black

hair would stop me in the narrow hallway by the produce tables

and grab the belt buckle and praise it. All along passing his hand

over my penis. “You are strong,” he would whisper, “like this lion.”

I would recoil from his touch and move away back to the front

where Papito would ask me about what bases I intended

to play next season on Los Cubanitos team. I never told my father,

or anyone, but the afternoon I showed up and the Fire Department

and police and ambulances huddled in the alleyway behind

Los Dos Toros, I knew something terrible had happened. Some

other kid had uttered the man’s groping and insisting on a kiss

in the almacén, the darkened storage room past the meat locker.

And another father had taken matters into his own hands.

But instead I found my father hosing the back door entrance,

washing the blood down to the alleyway. He told me to wait for him

in the car. The paramedics rolled out Papito, shot and dead on a stretcher,

victim of a hold up. The dark Cuban man who’d felt me up time

and again stood in the shade of a tree weeping and kicking the dirt

with blood encrusted shoes. I found out later he was the one who

slammed the assailant against the wall, and beat him unconscious.

Fuerte como un leon. The words fluttered like cow birds in the back

of my mind. Scattershot and ringing like the violence among the men.

Virgil Suárez is the author a multitude of books about the Cuban-American experience. His most recent collection is The Soviet Circus Comes to Havana & Other Stories. When he is not writing, he is out riding his Yamaha V-Star 1100 Classic up and down the Blue Highways of the Southeastern United States, stopping often enough to take a picture or two of abandoned places.

Kurt Luchs

Abduction

Brad, he said his name was, the man

about 30 in a red Mustang

who offered me a ride

that summer day between 7th and 8th grade,

the Summer of Love.

Every other radio was blaring Sgt. Pepper

but Brad was tuned to the classical station.

Debussy. Satie.

He was an adult in a suit.

I said yes.

All too soon he turned the wrong way

and then again and again, fast enough

that I couldn't think of jumping out.

We stopped miles out of town

on a dirt road in a cornfield.

He couldn't look at me.

Sweat glistened on his forehead

as he spoke of what he wanted to do.

His right hand was moist too,

crawling into my lap

like a fleshy pink tarantula.

I backed against the door on the passenger side.

I told him I only liked girls.

He said that was all right, he'd pay me.

Then he started to cry,

sobbing on my shoulder, his fingers

suddenly grasping with a different need,

the need not to be hated for his need.

I realized the power had shifted in my favor.

I patted him on the back, told him

it was all right and said it was time

to go home now.

He never said another word.

I never told a soul.

What amazes me most

is that I can still enjoy Satie.

Debussy was permanently ruined.

To this day the opening notes of La Mer

make me weep, I'm not sure for whom.

Kurt Luchs has poems published or forthcoming in Into the Void, Triggerfish Critical Review, Right Hand Pointing, Roanoke Review, Grey Sparrow Journal, Antiphon, Emrys Journal, and The Sun Magazine, among others, and won the 2017 Bermuda Triangle Poetry Prize. He has written humor for the New Yorker, the Onion and McSweeney's Internet Tendency. His poetry chapbook, One of These Things Is Not Like the Other, is forthcoming. More of his work, both poetry and humor, can be found at kurtluchs.com.

Brad, he said his name was, the man

about 30 in a red Mustang

who offered me a ride

that summer day between 7th and 8th grade,

the Summer of Love.

Every other radio was blaring Sgt. Pepper

but Brad was tuned to the classical station.

Debussy. Satie.

He was an adult in a suit.

I said yes.

All too soon he turned the wrong way

and then again and again, fast enough

that I couldn't think of jumping out.

We stopped miles out of town

on a dirt road in a cornfield.

He couldn't look at me.

Sweat glistened on his forehead

as he spoke of what he wanted to do.

His right hand was moist too,

crawling into my lap

like a fleshy pink tarantula.

I backed against the door on the passenger side.

I told him I only liked girls.

He said that was all right, he'd pay me.

Then he started to cry,

sobbing on my shoulder, his fingers

suddenly grasping with a different need,

the need not to be hated for his need.

I realized the power had shifted in my favor.

I patted him on the back, told him

it was all right and said it was time

to go home now.

He never said another word.

I never told a soul.

What amazes me most

is that I can still enjoy Satie.

Debussy was permanently ruined.

To this day the opening notes of La Mer

make me weep, I'm not sure for whom.

Kurt Luchs has poems published or forthcoming in Into the Void, Triggerfish Critical Review, Right Hand Pointing, Roanoke Review, Grey Sparrow Journal, Antiphon, Emrys Journal, and The Sun Magazine, among others, and won the 2017 Bermuda Triangle Poetry Prize. He has written humor for the New Yorker, the Onion and McSweeney's Internet Tendency. His poetry chapbook, One of These Things Is Not Like the Other, is forthcoming. More of his work, both poetry and humor, can be found at kurtluchs.com.

Jesse Millner 2 poems

What Do Men Want?

After Kim Addonizio

I want a cherry-red 1965 Mustang

with a manual transmission.

I want to be eighteen again

driving through the streets

of a strange place I’ve never visited before.

I want it to be a small town with

one bank, a single grocery store,

and a solitary bar where all the locals

drink their nights away. I want everyone

in the tavern to be a man who’s lost something.

I want half of them to be crying into their beer.

I want the other half to be laughing

at the men who are crying—in other words,

I want realism. I want the desperation

that comes from time and booze.

I want a shot of Jim Beam, please, and give

me back those ten years I wasted working

on that oil pipeline in Nebraska. It was a cold,

shitty job. All the women I met hated me

because I always smelled like smoke and distance.

The only thing I knew to talk about

was the way the daylight retreated

from a landscape that was emptiness,

drought, dust and the hallucinations

of ghost Irishmen building a railroad, dragging

the cottonwood ties to the gravel bed

that mostly wandered west. I want

a different memory filled with carnivals

and circus clowns. I want to ride a Ferris

wheel beneath a star-pierced sky

that is so beautiful, I’ll repeat it

seven times. I want the bearded lady

to fall in love with me. I want to have

six bearded children who will become

their own show, complete with fireworks

that go off after they do that thing with the lion.

After Kim Addonizio

I want a cherry-red 1965 Mustang

with a manual transmission.

I want to be eighteen again

driving through the streets

of a strange place I’ve never visited before.

I want it to be a small town with

one bank, a single grocery store,

and a solitary bar where all the locals

drink their nights away. I want everyone

in the tavern to be a man who’s lost something.

I want half of them to be crying into their beer.

I want the other half to be laughing

at the men who are crying—in other words,

I want realism. I want the desperation

that comes from time and booze.

I want a shot of Jim Beam, please, and give

me back those ten years I wasted working

on that oil pipeline in Nebraska. It was a cold,

shitty job. All the women I met hated me

because I always smelled like smoke and distance.

The only thing I knew to talk about

was the way the daylight retreated

from a landscape that was emptiness,

drought, dust and the hallucinations

of ghost Irishmen building a railroad, dragging

the cottonwood ties to the gravel bed

that mostly wandered west. I want

a different memory filled with carnivals

and circus clowns. I want to ride a Ferris

wheel beneath a star-pierced sky

that is so beautiful, I’ll repeat it

seven times. I want the bearded lady

to fall in love with me. I want to have

six bearded children who will become

their own show, complete with fireworks

that go off after they do that thing with the lion.

The likelihood of death

when standing next to a tall slash pine in a storm can be calculated by dividing the velocity of the

lightning bolt by the total number of days you wasted in fourth grade staring at that skinny little

girl with the amazing blue eyes, which seemed to glow with the sure knowledge of another world

where maybe love was possible and the principal breakfast food was chocolate ice cream. You

can also figure out how likely you are to deliver a newborn calf by multiplying the number of

dairy farms in your state by the elevation of each farm and then dividing everything by 12.

Curious about what happens when you die? Simply put fifteen lightning bugs in a jar and ask

fifteen people if the creatures are called bugs or fireflies. The bug number becomes the

numerator and the fly number the denominator in a fraction that must be multiplied by the speed

of light.

Once you’ve reached a final answer to these questions, write it down on lilac-perfumed

stationery, buy a tractor and drive west for 59 miles, then bury the answer by the side of the road.

If, however, there is roadkill within a mile of your burial, you must fetch the dead creature and

gently bury it with your answer. Make sure you cover the grave when you’re done so that other

contestants may not cheat their way into avoiding death by lightning, delivering calves, or

discovering the truth about Heaven and Hell.

Jesse Millner’s poems and prose have appeared in River Styx, Pearl, The Prose Poem Project, Gravel, Pithead Chapel, Wraparound South, The Best American Poetry 2013 and other literary magazines. He teaches writing courses at Florida Gulf Coast University in Fort Myers.

when standing next to a tall slash pine in a storm can be calculated by dividing the velocity of the

lightning bolt by the total number of days you wasted in fourth grade staring at that skinny little

girl with the amazing blue eyes, which seemed to glow with the sure knowledge of another world

where maybe love was possible and the principal breakfast food was chocolate ice cream. You

can also figure out how likely you are to deliver a newborn calf by multiplying the number of

dairy farms in your state by the elevation of each farm and then dividing everything by 12.

Curious about what happens when you die? Simply put fifteen lightning bugs in a jar and ask

fifteen people if the creatures are called bugs or fireflies. The bug number becomes the

numerator and the fly number the denominator in a fraction that must be multiplied by the speed

of light.

Once you’ve reached a final answer to these questions, write it down on lilac-perfumed

stationery, buy a tractor and drive west for 59 miles, then bury the answer by the side of the road.

If, however, there is roadkill within a mile of your burial, you must fetch the dead creature and

gently bury it with your answer. Make sure you cover the grave when you’re done so that other

contestants may not cheat their way into avoiding death by lightning, delivering calves, or

discovering the truth about Heaven and Hell.

Jesse Millner’s poems and prose have appeared in River Styx, Pearl, The Prose Poem Project, Gravel, Pithead Chapel, Wraparound South, The Best American Poetry 2013 and other literary magazines. He teaches writing courses at Florida Gulf Coast University in Fort Myers.

Sean Sexton 4 poems

Last of the Calves

At the gate, the last of the calves

balk, turn and fly away as toward

some great wisdom, hurrying back

to the fond allure of the past,

their last suckle, perhaps— anywhere,

save through the loathsome door

just opened in the world.

The herd has crossed over, resumed its work

yet twenty truants remain, scattering

perilously as if no promise

lay beyond that brink.

Headlong they go, creatures

possessed, close to heaven

as the days they were born.

At the gate, the last of the calves

balk, turn and fly away as toward

some great wisdom, hurrying back

to the fond allure of the past,

their last suckle, perhaps— anywhere,

save through the loathsome door

just opened in the world.

The herd has crossed over, resumed its work

yet twenty truants remain, scattering

perilously as if no promise

lay beyond that brink.

Headlong they go, creatures

possessed, close to heaven

as the days they were born.

Not

After Seamus Heaney

Not the listless woods these days,

their ongoing summer song

same as the year-round sound in my head.

Not the thick, bottomless mud in gateways

difficult as winter to cross, nor

the next unbridling rain,

wrung out of any torporous hour--

dark, light, morning, night.

And not the suffocation of breath

in the thick, sunsoaked air, but you,

four years gone by September,

disappearing like a whole calf-crop one quick day,

with only us to say, you were here at all.

After Seamus Heaney

Not the listless woods these days,

their ongoing summer song

same as the year-round sound in my head.

Not the thick, bottomless mud in gateways

difficult as winter to cross, nor

the next unbridling rain,

wrung out of any torporous hour--

dark, light, morning, night.

And not the suffocation of breath

in the thick, sunsoaked air, but you,

four years gone by September,

disappearing like a whole calf-crop one quick day,

with only us to say, you were here at all.

The Barren Heifer

Today is the day, the last crimson dawn

for the barren heifer, a truck to the abattoir,

soon to arrive. Half a year she stayed,

up to her withers in feast in the set-aside

pasture, with orphans, errant bulls

a rickety cow, and others on last legs.

We drove her with an ancient, blind dam

who knew the gate, stored them together

overnight in the pens to keep her blood quiet.

She has no light, no soil within to plant.

Dinner by dinner, we’ll send her to heaven,

our bellies her path, one way or another.

Today is the day, the last crimson dawn

for the barren heifer, a truck to the abattoir,

soon to arrive. Half a year she stayed,

up to her withers in feast in the set-aside

pasture, with orphans, errant bulls

a rickety cow, and others on last legs.

We drove her with an ancient, blind dam

who knew the gate, stored them together

overnight in the pens to keep her blood quiet.

She has no light, no soil within to plant.

Dinner by dinner, we’ll send her to heaven,

our bellies her path, one way or another.

Things Found Caught in the Fence

A late April Inventory

Innumerable wisps of cow’s tails,

silken, black, tawny, and brown.

Tiny spider webs,

(tent-fashioned & occasional)

upon wire barbs.

A single white tuft of down.

Remains of the butcher bird’s quarry:

2 frogs (desiccated), a locust,

baby red rat snake, draped,

3 small beetles, dark, shiny,

all impaled—

and hollowed out.

Dew.

A buckthorn bush, privet,

and several thistles

grown up and through.

Four equal-sized, ongoing, eternal spaces,

Light.

Sean Sexton received an Individual Artist’s Fellowship from the State of Florida in 2000-2001. He is author of Blood Writing, Poems, Anhinga Press, 2009, The Empty Tomb, University of Alabama Slash Pine Press, 2014, and Descent, Yellow Jacket Press, 2018. May Darkness Restore, Poems, Press 53 is due out in early 2019. He has performed annually at the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Elko, Nevada, and presented at the The Miami Book Fair International, O' Miami, and Other Words Arts Literary Conference in Tampa, FL. On Sept 1, 2016, He became the inaugural Poet Laureate of Indian River County.

A late April Inventory

Innumerable wisps of cow’s tails,

silken, black, tawny, and brown.

Tiny spider webs,

(tent-fashioned & occasional)

upon wire barbs.

A single white tuft of down.

Remains of the butcher bird’s quarry:

2 frogs (desiccated), a locust,

baby red rat snake, draped,

3 small beetles, dark, shiny,

all impaled—

and hollowed out.

Dew.

A buckthorn bush, privet,

and several thistles

grown up and through.

Four equal-sized, ongoing, eternal spaces,

Light.

Sean Sexton received an Individual Artist’s Fellowship from the State of Florida in 2000-2001. He is author of Blood Writing, Poems, Anhinga Press, 2009, The Empty Tomb, University of Alabama Slash Pine Press, 2014, and Descent, Yellow Jacket Press, 2018. May Darkness Restore, Poems, Press 53 is due out in early 2019. He has performed annually at the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Elko, Nevada, and presented at the The Miami Book Fair International, O' Miami, and Other Words Arts Literary Conference in Tampa, FL. On Sept 1, 2016, He became the inaugural Poet Laureate of Indian River County.

Maureen Seaton 2 poems

A Pod of Whales

for L

A person can die of night terrors—right there in the middle of sleep, their hearts might stop, you

say, as if I don’t believe you. Sometimes you dream so loud your life flashes before my eyes,

your screams raise ghost stories. Against my will, I am your wide-eyed witness. It’s been years

since we slept spooned and cozy, and I’ve almost forgotten I miss you. Still, I would go back to

your race-betrayed American past and keep you safe from all the things a child should never

have to see. You’d snore like any tired soul wrapped warm beside me, wake up yawning. Now a

pod of pilot whales is stranded in shallows off the coast of Florida. They’ll die together, it’s true,

as the pod will never abandon its wounded. Who can reconcile this cuspy hold on life, who sleep

through the crescendo of hearts stopping?

for L

A person can die of night terrors—right there in the middle of sleep, their hearts might stop, you

say, as if I don’t believe you. Sometimes you dream so loud your life flashes before my eyes,

your screams raise ghost stories. Against my will, I am your wide-eyed witness. It’s been years

since we slept spooned and cozy, and I’ve almost forgotten I miss you. Still, I would go back to

your race-betrayed American past and keep you safe from all the things a child should never

have to see. You’d snore like any tired soul wrapped warm beside me, wake up yawning. Now a

pod of pilot whales is stranded in shallows off the coast of Florida. They’ll die together, it’s true,

as the pod will never abandon its wounded. Who can reconcile this cuspy hold on life, who sleep

through the crescendo of hearts stopping?

Jesus on the Beach

Because I lived on the beach in what some folks call old Florida, there were a fair number of

ponytailed guys in the neighborhood who resembled Jesus. One, in particular, drove a pick-up

and loved animals, even beach cats. I don’t know if my neighbor, Pete, was a poet or not. He

looked like a middle-aged, hard-drugging Jesus to me, so he could have been. We said hi to each

other most evenings, and if a hurricane came along, I knew he’d share his canned chili and Easy

Cheese with me. One weekend he parked his truck crooked to keep tourists out of our little lot

and he blocked my space by accident. When I politely tapped on his door to ask him to move his

truck, he yelled from the shower: Park on the goddamn grass, asshole. His wife found him dead

the next day on the bathroom floor. He was shaving, she said, and he just keeled over. Jesus, I

said to myself.

Maureen Seaton has authored twenty poetry collections, both solo and collaborative. Her awards include the Iowa Poetry Prize and Lambda Literary Award, an NEA fellowship and the Pushcart. Her memoir, Sex Talks to Girls (U. of Wisconsin Press), also garnered a Lammy. A new poetry collection, Fisher, is out from Black Lawrence Press and a new anthology, Reading Queer: Poetry in a Time of Chaos, co-edited with Neil de la Flor, is out from Anhinga Press. Seaton teaches Creative Writing at the University of Miami, Florida.

Because I lived on the beach in what some folks call old Florida, there were a fair number of

ponytailed guys in the neighborhood who resembled Jesus. One, in particular, drove a pick-up

and loved animals, even beach cats. I don’t know if my neighbor, Pete, was a poet or not. He

looked like a middle-aged, hard-drugging Jesus to me, so he could have been. We said hi to each

other most evenings, and if a hurricane came along, I knew he’d share his canned chili and Easy

Cheese with me. One weekend he parked his truck crooked to keep tourists out of our little lot

and he blocked my space by accident. When I politely tapped on his door to ask him to move his

truck, he yelled from the shower: Park on the goddamn grass, asshole. His wife found him dead

the next day on the bathroom floor. He was shaving, she said, and he just keeled over. Jesus, I

said to myself.

Maureen Seaton has authored twenty poetry collections, both solo and collaborative. Her awards include the Iowa Poetry Prize and Lambda Literary Award, an NEA fellowship and the Pushcart. Her memoir, Sex Talks to Girls (U. of Wisconsin Press), also garnered a Lammy. A new poetry collection, Fisher, is out from Black Lawrence Press and a new anthology, Reading Queer: Poetry in a Time of Chaos, co-edited with Neil de la Flor, is out from Anhinga Press. Seaton teaches Creative Writing at the University of Miami, Florida.

D. Nurkse 3 poems

The Old One

When you were a child, you were afraid of dying. You asked your mother, exactly how is it like going to sleep? The fly who tucks its legs against its chest–-what does it do next? The room was bright though the blinds were drawn. Your mother rocked you and cried softly. You could barely

hear her sniffle, but you licked a dab of salt.

Swiftly you came of age. You told your lover, I won’t know how to leave you. She unhooked her pleated skirt and lay beside you. She stroked your hair. Reaching over, you felt her amber pendant, strangely warm for a mineral, almost moist. Her calm breath soothed you.

Now it’s death you meet. You say, I’m not so sure anymore, and he cries. He undresses and lies beside you. His tears are pungent, but he’s old himself. In a moment he’ll want to piss. He’ll long for a cigarette, a sprig of grapes, news of Kaunas. His big toe will itch. His femur will throb. He’ll miss the friends of his boyhood, Michael and little Gabriel, the smoky taste of kielbasa, the lilt of a village lullaby.

He’s bawling now, but in an hour he won’t remember why he came into the room.

When you were a child, you were afraid of dying. You asked your mother, exactly how is it like going to sleep? The fly who tucks its legs against its chest–-what does it do next? The room was bright though the blinds were drawn. Your mother rocked you and cried softly. You could barely

hear her sniffle, but you licked a dab of salt.

Swiftly you came of age. You told your lover, I won’t know how to leave you. She unhooked her pleated skirt and lay beside you. She stroked your hair. Reaching over, you felt her amber pendant, strangely warm for a mineral, almost moist. Her calm breath soothed you.

Now it’s death you meet. You say, I’m not so sure anymore, and he cries. He undresses and lies beside you. His tears are pungent, but he’s old himself. In a moment he’ll want to piss. He’ll long for a cigarette, a sprig of grapes, news of Kaunas. His big toe will itch. His femur will throb. He’ll miss the friends of his boyhood, Michael and little Gabriel, the smoky taste of kielbasa, the lilt of a village lullaby.

He’s bawling now, but in an hour he won’t remember why he came into the room.

A Second Of Happiness

When we were children, she says, how we wanted to be old-–to walk with exciting buckling canes, to be swathed in trusses and bandages, to bump into each other mouthing excuse me, to lap up liquid food, as a moment ago, when we were babies.

Perhaps then, we thought, we would look back, and see happiness, burning like a fire in the mountains.

When we were lovers, she says, how we longed to be parted, to live in distant cities, Duluth and Vancouver, under assumed names, working nights in the central post office, or as shipping clerks in huge factories.

Perhaps there would come an instant, a split-second, a final blink, when we would look back and understand happiness, that consumes everything.

After surgery, she says, how I hoped to live forever, though all I meant by that was: another second.

Another drop pearls in the spigot. The blind dog hunts in a dream.

When we were children, she says, how we wanted to be old-–to walk with exciting buckling canes, to be swathed in trusses and bandages, to bump into each other mouthing excuse me, to lap up liquid food, as a moment ago, when we were babies.

Perhaps then, we thought, we would look back, and see happiness, burning like a fire in the mountains.

When we were lovers, she says, how we longed to be parted, to live in distant cities, Duluth and Vancouver, under assumed names, working nights in the central post office, or as shipping clerks in huge factories.

Perhaps there would come an instant, a split-second, a final blink, when we would look back and understand happiness, that consumes everything.

After surgery, she says, how I hoped to live forever, though all I meant by that was: another second.

Another drop pearls in the spigot. The blind dog hunts in a dream.

Twilight

The child is hiding in the pear orchard and I shout her name but she doesn’t budge or rustle. Or if she does, it’s because all leaves flinch, tremble, and cough. Anything less would be suspicious.

But I know it’s crazy laughter, suppressed to the limit of human strength, that makes a scritch like a vole’s tail brushing marl.

Almost-relief that she doesn’t amble out, hiccuping, examining her thumbnail critically. Perhaps she’s helpless against my will.

The previous owner nailed a ladder to a fuzzy trunk, and buckets in the forked branches, in the summer before the first storms. Bottoms are rusted out, a rung is missing. Here’s the red handle of a shears, the blade is a crease in moss.

A cat sidles from the thicket, annoyed at the commotion. A familiar slouch: is that Twilight?

But you know how people resemble each other? Mr. Pogue and Arthur Perlo? Dr. Platt with his plaid earmuffs and the nameless librarian? How Tuesday is like Thursday? As if there were a template they all vie to fit? This cat too is the same but different: gray mark on one haunch. Tattered ear, where the original had no ear. But the identical contemptuous yawn.

Peraps I should just be calling: Child! Child!

When I turn back to the porch, the laughter, meaning the silence, will intensify. Time to turn up the wick in the oil lamp, set the table, find a match for the citronella candle, cut the bread and pour the sticky wine. But all my gestures are double. I’m miming myself. To amaze you with your boredom, there where you watch, in the halo of bees.

D. Nurkse's eleventh poetry collection, Love in the Last Days, was published by Knopf in 2017.

The child is hiding in the pear orchard and I shout her name but she doesn’t budge or rustle. Or if she does, it’s because all leaves flinch, tremble, and cough. Anything less would be suspicious.

But I know it’s crazy laughter, suppressed to the limit of human strength, that makes a scritch like a vole’s tail brushing marl.

Almost-relief that she doesn’t amble out, hiccuping, examining her thumbnail critically. Perhaps she’s helpless against my will.

The previous owner nailed a ladder to a fuzzy trunk, and buckets in the forked branches, in the summer before the first storms. Bottoms are rusted out, a rung is missing. Here’s the red handle of a shears, the blade is a crease in moss.

A cat sidles from the thicket, annoyed at the commotion. A familiar slouch: is that Twilight?

But you know how people resemble each other? Mr. Pogue and Arthur Perlo? Dr. Platt with his plaid earmuffs and the nameless librarian? How Tuesday is like Thursday? As if there were a template they all vie to fit? This cat too is the same but different: gray mark on one haunch. Tattered ear, where the original had no ear. But the identical contemptuous yawn.

Peraps I should just be calling: Child! Child!

When I turn back to the porch, the laughter, meaning the silence, will intensify. Time to turn up the wick in the oil lamp, set the table, find a match for the citronella candle, cut the bread and pour the sticky wine. But all my gestures are double. I’m miming myself. To amaze you with your boredom, there where you watch, in the halo of bees.

D. Nurkse's eleventh poetry collection, Love in the Last Days, was published by Knopf in 2017.

Jane Rosenberg LaForge

Defect

By the time they identified

the flaw, a tilt

of the hips

as though you were

temporarily itching

a scratch you did not

ever wish to see,

it was too late

for braces, for relearning

the basics, the un-plaiting

of muscles determined to hold on

to this mistake

terminally. To make it

natural, when it wasn’t;

to make it like so many

other failings

that didn’t make for special

notice. That was never

the family style.

The spine can be tricky,

just as synapses are over-bunched

as blossoms fighting for dominance,

the weaker shielded

from nourishment,

like a twin that dies

in uterine grief.

Now that you are older

and can no longer contain

these errors in public;

that they impede your operation

and appearance as if you were mechanical

and wanting for maintenance;

and for years of coping

you are blameful,

lacking remorse for

this lurch and slide,

the overcompensation for something

you thought somatic,

but time has made it real

if still not relevant enough

for true service

and suffering.

Jane Rosenberg LaForge lives in New York. She is a novelist, poet, and memoirist, having most recently published The Hawkman: A Fairy Tale of the Great War (Amberjack Publishing); Daphne and Her Discontents (Ravenna Press); and An Unsuitable Princess: A True Fantasy/A Fantastical Memoir (Jaded Ibis Press). Her poetry has most recently appeared in Peacock Journal, Counterclock and Poets Reading the News.

By the time they identified

the flaw, a tilt

of the hips

as though you were

temporarily itching

a scratch you did not

ever wish to see,

it was too late

for braces, for relearning

the basics, the un-plaiting

of muscles determined to hold on

to this mistake

terminally. To make it

natural, when it wasn’t;

to make it like so many

other failings

that didn’t make for special

notice. That was never

the family style.

The spine can be tricky,

just as synapses are over-bunched

as blossoms fighting for dominance,

the weaker shielded

from nourishment,

like a twin that dies

in uterine grief.

Now that you are older

and can no longer contain

these errors in public;

that they impede your operation

and appearance as if you were mechanical

and wanting for maintenance;

and for years of coping

you are blameful,

lacking remorse for

this lurch and slide,

the overcompensation for something

you thought somatic,

but time has made it real

if still not relevant enough

for true service

and suffering.

Jane Rosenberg LaForge lives in New York. She is a novelist, poet, and memoirist, having most recently published The Hawkman: A Fairy Tale of the Great War (Amberjack Publishing); Daphne and Her Discontents (Ravenna Press); and An Unsuitable Princess: A True Fantasy/A Fantastical Memoir (Jaded Ibis Press). Her poetry has most recently appeared in Peacock Journal, Counterclock and Poets Reading the News.

Lola Haskins 3 poems

The Second Through Fourth Grades Put on We Haz Jazz.

Lydia, in a glittery red dress

lugs her bass on stage

and stands in front

of the cardboard piano.

The other kids—the girls

in pumps and pastel gowns,

azaleas wilting in their hair,

the suited flat—capped boys--

belt out Paper Moon

while Lydia plucks.

Her instrument is bigger

than she is. Her instrument

will always be bigger than she is.

Lydia, in a glittery red dress

lugs her bass on stage

and stands in front

of the cardboard piano.

The other kids—the girls

in pumps and pastel gowns,

azaleas wilting in their hair,

the suited flat—capped boys--

belt out Paper Moon

while Lydia plucks.

Her instrument is bigger

than she is. Her instrument

will always be bigger than she is.

Redemption

When the sky turns blue I'm drawn to look beyond it but every time

I try, the fog rolls in off the Golden Gate again. And my first love

jumps again and is scattered on the gray waves again like the

flowers people throw from boats. And I walk the fire road again to

where the dark pines open to hills smeared with red. And I take the

turn up at the fork as I always have, because I know the other way

leads to where I don't belong.

When the fog rolls away, everything that used to be there is gone.

No house on Vallejo Street, no back door whose chain rattled every

night at three after the caller I never saw had hung up. No police

dog, baring his teeth in the yard. But the story isn't over because

what's left is no protection against last year's man who said he

loved me then night after night idled his car in my driveway in the

dark then knocked my mailbox off its post- it fell like a punched

child—and finally broke into my garage and took what he'd wanted

all along-- not my bicycle but boxes and boxes of my self. I can

still see my faces on the backs of those books, burning. He must

have enjoyed watching each tiny image, each witch, curl and turn to

ash. He must have warmed his hands over the fire.

The sky is blue again and far above the woods an eagle crosses.

When the sky turns blue I'm drawn to look beyond it but every time

I try, the fog rolls in off the Golden Gate again. And my first love

jumps again and is scattered on the gray waves again like the

flowers people throw from boats. And I walk the fire road again to

where the dark pines open to hills smeared with red. And I take the

turn up at the fork as I always have, because I know the other way

leads to where I don't belong.

When the fog rolls away, everything that used to be there is gone.

No house on Vallejo Street, no back door whose chain rattled every

night at three after the caller I never saw had hung up. No police

dog, baring his teeth in the yard. But the story isn't over because

what's left is no protection against last year's man who said he

loved me then night after night idled his car in my driveway in the

dark then knocked my mailbox off its post- it fell like a punched

child—and finally broke into my garage and took what he'd wanted

all along-- not my bicycle but boxes and boxes of my self. I can

still see my faces on the backs of those books, burning. He must

have enjoyed watching each tiny image, each witch, curl and turn to

ash. He must have warmed his hands over the fire.

The sky is blue again and far above the woods an eagle crosses.

Across the Tops

our path runs narrow through heather whose purple

sprigs, being September's, are mixed with brown. A

bleak sacramental wind cleans us for Rhylstone Cross

and the miles that may remain to us under this dark-

gray roiling sky whose blue patches open and close in

a blink. May no step we take go unnoticed, may we

mark the whirr and complaint of each flushed grouse,

and may we glory in the cold forever, for it is the cold

of the sea, which is grass and heather and birds and

sky, and most of all the breaking light that gleams,

wild and holy, in our eyes.

Lola Haskins divides her time between Gainesville and North Yorkshire. Her newest collection, Asylum, oriented around the states of mind of John Clare, is due from Pitt in Spring, 2019. The book before that, How Small, Confronting Morning (Jacar, 2016), was plein air poetry set in inland Florida. She currently serves as Honorary Chancellor for the Florida State Poets Association. Past honors include the Iowa Poetry Prize, two NEAs, two Florida Book Awards, and the Emily Dickinson prize from Poetry Society of America. For more information, please visit her at www.lolahaskins.com.

our path runs narrow through heather whose purple

sprigs, being September's, are mixed with brown. A

bleak sacramental wind cleans us for Rhylstone Cross

and the miles that may remain to us under this dark-

gray roiling sky whose blue patches open and close in

a blink. May no step we take go unnoticed, may we

mark the whirr and complaint of each flushed grouse,

and may we glory in the cold forever, for it is the cold

of the sea, which is grass and heather and birds and

sky, and most of all the breaking light that gleams,

wild and holy, in our eyes.

Lola Haskins divides her time between Gainesville and North Yorkshire. Her newest collection, Asylum, oriented around the states of mind of John Clare, is due from Pitt in Spring, 2019. The book before that, How Small, Confronting Morning (Jacar, 2016), was plein air poetry set in inland Florida. She currently serves as Honorary Chancellor for the Florida State Poets Association. Past honors include the Iowa Poetry Prize, two NEAs, two Florida Book Awards, and the Emily Dickinson prize from Poetry Society of America. For more information, please visit her at www.lolahaskins.com.

Jeannie E. Roberts

Awaken

—After Gretchen Marquette’s poem “What We Will Love with the Time We Have Left”

“The breeze at dawn has secrets to tell you. Don’t go back to sleep.” —Rumi

When we awaken, we may celebrate steam rising, the first sips of sunrise

where lake ice yawns neutrals, breaks white. The clarity of cold, its frozen

stillness. Constellations. The burning trail of stars. Hats. Scarves. Handmade

mittens. Bundles of children laughing, shaping angels in snow.

Maples, lindens, and oaks. Landscapes of lemon and scarlet, vermillion.

The tangle of understory, where mice skitter and stumps rot. The fragrance

of decay. Well-worn work gloves. Bamboo rakes. The muscular ache

of outdoor chores. Bonfires fueled with autumn’s leavings. Marshmallows,

their molten centers. The drip and stickiness of caramel apples. The small

softness of your child’s hand. Each step taken as you walk through alfalfa

fields. Clouds. The meadow where you lay dreaming, imagining dogs,

dragons, and dinosaurs. Plants, their power to grow, flourish between

concrete cracks. The green alignment of crops and pines, rural symmetry.

The squirrel drinking from backyard birdbaths, the tall dog following suit.

Crystals forming after hot coffee is poured over ice cream, the dissolving

texture that sweetens our lips. The sparkle of July in children’s eyes.

The scent of fresh starts. Lilacs blossoming. Buds burgeoning. The beating

of grouse. Swallowtails sailing midst maidenhair ferns. Rivers. Flood-beaten

banks. Haphazard heaps of driftwood. The surface glide of water striders.

The backward dance of crayfish. The call and commotion of American cliff

swallows. Precisely-made-mud nests. Bogs, peepers, and pollywogs. Youth,

and its bringing on. Age, and its letting go. The beauty of imperfection.

The gifts of brokenness. Poems, knowing that the breeze at dawn has secrets

to tell us.

Jeannie E. Roberts lives in an inspiring setting near Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin, where she writes, draws and paints, and often photographs her natural surroundings. She has authored four poetry collections, including the most recent The Wingspan of Things (Dancing Girl Press, 2017).

—After Gretchen Marquette’s poem “What We Will Love with the Time We Have Left”

“The breeze at dawn has secrets to tell you. Don’t go back to sleep.” —Rumi

When we awaken, we may celebrate steam rising, the first sips of sunrise

where lake ice yawns neutrals, breaks white. The clarity of cold, its frozen

stillness. Constellations. The burning trail of stars. Hats. Scarves. Handmade

mittens. Bundles of children laughing, shaping angels in snow.

Maples, lindens, and oaks. Landscapes of lemon and scarlet, vermillion.

The tangle of understory, where mice skitter and stumps rot. The fragrance

of decay. Well-worn work gloves. Bamboo rakes. The muscular ache

of outdoor chores. Bonfires fueled with autumn’s leavings. Marshmallows,

their molten centers. The drip and stickiness of caramel apples. The small

softness of your child’s hand. Each step taken as you walk through alfalfa

fields. Clouds. The meadow where you lay dreaming, imagining dogs,

dragons, and dinosaurs. Plants, their power to grow, flourish between

concrete cracks. The green alignment of crops and pines, rural symmetry.

The squirrel drinking from backyard birdbaths, the tall dog following suit.

Crystals forming after hot coffee is poured over ice cream, the dissolving

texture that sweetens our lips. The sparkle of July in children’s eyes.

The scent of fresh starts. Lilacs blossoming. Buds burgeoning. The beating

of grouse. Swallowtails sailing midst maidenhair ferns. Rivers. Flood-beaten

banks. Haphazard heaps of driftwood. The surface glide of water striders.

The backward dance of crayfish. The call and commotion of American cliff

swallows. Precisely-made-mud nests. Bogs, peepers, and pollywogs. Youth,

and its bringing on. Age, and its letting go. The beauty of imperfection.

The gifts of brokenness. Poems, knowing that the breeze at dawn has secrets

to tell us.

Jeannie E. Roberts lives in an inspiring setting near Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin, where she writes, draws and paints, and often photographs her natural surroundings. She has authored four poetry collections, including the most recent The Wingspan of Things (Dancing Girl Press, 2017).

Elizabeth Jacobson 3 poems

Melancholia

Completely unsheathed, a frangipani

besides a fence, facing a river.

The fragility of bare finger-like tips.

The tender scaled boughs.

In the absence of leaves, leaves sprout forth.

In the absence of nectar, a sphinx moth

appears. Frangipani. Your aromatic selves,

when they bloom— each one

a love poem; each one a hoax.

Completely unsheathed, a frangipani

besides a fence, facing a river.

The fragility of bare finger-like tips.

The tender scaled boughs.

In the absence of leaves, leaves sprout forth.

In the absence of nectar, a sphinx moth

appears. Frangipani. Your aromatic selves,

when they bloom— each one

a love poem; each one a hoax.

Hottest Year on Record

Long Marriage

I have about 1000 postcard stamps, she says,

as his hand lifts her pajama shirt,

slides down her spine.

Oh, that feels good, she says, tucking a pillow between her legs, can you rub this hip?

I went to the post office yesterday and bought more by mistake, she says.

What? he says, pulling her closer, moving his hand across the small of her back.

And I cut my finger on the metal tab while closing the envelope I was mailing.

Look, she says, turning and placing her finger in his mouth.

Ooo, he says.

I organized all the stamps, by the way, she says.

I put them in one of those free parchment envelopes

with the postal service eagle head.

He slips his fingers lower, into her moistness.

Ummm, she says. I’ve got to get up.

Because they did it a few mornings last week,

he thinks they are going to do it every morning now.

That’s good, she says, but I’ve really got to get up.

I need to make coffee.

Just relax, he says, kissing behind her ears,

shifting her shoulders and pressing her into the pillows.

She looks up at him, his eyes are wide open.

The loose skin on his face pulled down by gravity.

They are more sensitive now than when they were younger.

The membranes a little thinner,

their nerve endings more fine-tuned.

Elizabeth Jacobson is the author of Not into the Blossoms and Not into the Air, winner of the New Measure Poetry Prize, selected by Marianne Boruch, Parlor Press, 2019. Are the Children Make Believe?, a chapbook, was recently published by dancing girl press. New poems are forthcoming in the American Poetry Review, On The Seawall, Plume, Terrain and Vox Populi. She lives in Santa Fe, NM and directs the WingSpan Poetry Project.

I have about 1000 postcard stamps, she says,

as his hand lifts her pajama shirt,

slides down her spine.

Oh, that feels good, she says, tucking a pillow between her legs, can you rub this hip?

I went to the post office yesterday and bought more by mistake, she says.

What? he says, pulling her closer, moving his hand across the small of her back.

And I cut my finger on the metal tab while closing the envelope I was mailing.

Look, she says, turning and placing her finger in his mouth.

Ooo, he says.

I organized all the stamps, by the way, she says.

I put them in one of those free parchment envelopes

with the postal service eagle head.

He slips his fingers lower, into her moistness.

Ummm, she says. I’ve got to get up.

Because they did it a few mornings last week,

he thinks they are going to do it every morning now.

That’s good, she says, but I’ve really got to get up.

I need to make coffee.

Just relax, he says, kissing behind her ears,

shifting her shoulders and pressing her into the pillows.

She looks up at him, his eyes are wide open.

The loose skin on his face pulled down by gravity.

They are more sensitive now than when they were younger.

The membranes a little thinner,

their nerve endings more fine-tuned.

Elizabeth Jacobson is the author of Not into the Blossoms and Not into the Air, winner of the New Measure Poetry Prize, selected by Marianne Boruch, Parlor Press, 2019. Are the Children Make Believe?, a chapbook, was recently published by dancing girl press. New poems are forthcoming in the American Poetry Review, On The Seawall, Plume, Terrain and Vox Populi. She lives in Santa Fe, NM and directs the WingSpan Poetry Project.

Lucia Leao 2 poems

a kind of marriage

for Oswaldo Martins

the erotic poems were sent to ashes

when he died, but his wife grabbed a few

lower-case beginnings of lines becoming

dust in her eyes, but she didn’t cry

in fictional women he praised her,

and she was happy for him, for that

island of so many lakes, the imagination

she wore with him, his body

for Oswaldo Martins

the erotic poems were sent to ashes

when he died, but his wife grabbed a few

lower-case beginnings of lines becoming

dust in her eyes, but she didn’t cry

in fictional women he praised her,

and she was happy for him, for that

island of so many lakes, the imagination

she wore with him, his body

the simple visibility of the sea

is a curse

of course I know

the moment you arrive

you are already gone.

I call you my identity not

Caribbean not

European not,

the knot the hinge

this land where I insist.

Lucia Leao is a translator and writer. Her poems have been published in Chariton Review, SoFloPoJo, and in Brazilian websites dedicated to poetry. Leao has published a collection of short stories and is co-author of a young-adult novel, both published in Portuguese, in Brazil. She has a bachelor’s degree in English and Literatures from Rio de Janeiro State University, Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), a master’s degree in Brazilian Literature from UERJ and a master’s in print journalism from University of Miami. She was born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

is a curse

of course I know

the moment you arrive

you are already gone.

I call you my identity not

Caribbean not

European not,

the knot the hinge

this land where I insist.

Lucia Leao is a translator and writer. Her poems have been published in Chariton Review, SoFloPoJo, and in Brazilian websites dedicated to poetry. Leao has published a collection of short stories and is co-author of a young-adult novel, both published in Portuguese, in Brazil. She has a bachelor’s degree in English and Literatures from Rio de Janeiro State University, Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), a master’s degree in Brazilian Literature from UERJ and a master’s in print journalism from University of Miami. She was born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

W.T. Pfefferle 2 poems

Breathing

My daughter puffs

at me, puffs out her cheeks

when she’s mad. Puffs of dust

as she runs out of the yard.

She collapses in autumn

in my wife’s arms, and we

take her to the hospital

when her skin goes white then blue.

She is last born, stubborn,

the one we think of as a runt.

She thinks she’s the leader of

the pack, the one who will get

out of Wisconsin before the rest of us.

She winces to life when the doctor

puts the needle between her ribs,

when he blows air through a plastic hose.

Later, she rides home in back, a little inhaler

in her fist, her instructions to use it

and to slow down. I see her grimace

down at it. She puts it in a blue jeans pocket

when we hit the driveway. She runs across

the yard, up a tree. I see her take a puff,

put the damn thing away again,

and look out across the field,

south and west and away from here.

My daughter puffs

at me, puffs out her cheeks

when she’s mad. Puffs of dust

as she runs out of the yard.

She collapses in autumn

in my wife’s arms, and we

take her to the hospital

when her skin goes white then blue.

She is last born, stubborn,

the one we think of as a runt.

She thinks she’s the leader of

the pack, the one who will get

out of Wisconsin before the rest of us.

She winces to life when the doctor

puts the needle between her ribs,

when he blows air through a plastic hose.

Later, she rides home in back, a little inhaler

in her fist, her instructions to use it

and to slow down. I see her grimace

down at it. She puts it in a blue jeans pocket

when we hit the driveway. She runs across

the yard, up a tree. I see her take a puff,

put the damn thing away again,

and look out across the field,

south and west and away from here.

Tuscaloosa

Walter at the Tuscaloosa Greyhound station

tells me that Jupiter will fill the sky tonight.

He says that it’s been 500 years since it’s happened,

and that the best time to see it is at midnight.

He draws a circle with his finger in the air, the size of an apple,

and says, “It’ll be shiny and red if you look at it through a scope.”

A girl who bolted and left without paying, peers through the window,

motioning to us. She’s left her keys behind.

Walter picks them up, spins the ring around his finger.

“Come and get ‘em,” he mouths to the girl.

Later, at midnight, I sit on the bench out front of the station.

I don’t see anything in the sky over Tuscaloosa.

It’s just dark up there. Just inky.

Walter caught his bus. And I’ve got the keys.

W.T. Pfefferle is the author of The Meager Life and Modest Times of Pop Thorndale, My Coolest Shirt, and Poets on Place. His poems are in Antioch Review, Connecticut Review, Gargoyle Magazine, Georgetown Review, Greensboro Review, Hayden's Ferry Review, Indiana Review, Mississippi Review, New Orleans Review, Nimrod, North American Review, Ohio Review, South Carolina Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, and others.

Walter at the Tuscaloosa Greyhound station

tells me that Jupiter will fill the sky tonight.

He says that it’s been 500 years since it’s happened,

and that the best time to see it is at midnight.

He draws a circle with his finger in the air, the size of an apple,

and says, “It’ll be shiny and red if you look at it through a scope.”

A girl who bolted and left without paying, peers through the window,

motioning to us. She’s left her keys behind.

Walter picks them up, spins the ring around his finger.

“Come and get ‘em,” he mouths to the girl.

Later, at midnight, I sit on the bench out front of the station.

I don’t see anything in the sky over Tuscaloosa.

It’s just dark up there. Just inky.

Walter caught his bus. And I’ve got the keys.

W.T. Pfefferle is the author of The Meager Life and Modest Times of Pop Thorndale, My Coolest Shirt, and Poets on Place. His poems are in Antioch Review, Connecticut Review, Gargoyle Magazine, Georgetown Review, Greensboro Review, Hayden's Ferry Review, Indiana Review, Mississippi Review, New Orleans Review, Nimrod, North American Review, Ohio Review, South Carolina Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, and others.

John L. Stanizzi 2 poems

Phonebooth

I found one of the phonebooths I used to call you from 40 years ago. It was in the white room of

a museum, not connected to anything. It was just a “piece.” When no one was looking I rushed inside

and called you. When you answered I couldn’t speak.

I found one of the phonebooths I used to call you from 40 years ago. It was in the white room of

a museum, not connected to anything. It was just a “piece.” When no one was looking I rushed inside

and called you. When you answered I couldn’t speak.

It’s Not the Heat…

Humidity is fatigue, a scrim, that which holds the trees down by their shoulders or

shakes them, fills shadows with fat, bloats bark, prompts birdsong to echo, frogs to stillness

in warm shallows, and when rain comes, humid air breaks into pieces, and fills

each droplet with a tiny cloud.

John L. Stanizzi is author of the full-length collections Ecstasy Among Ghosts, Sleepwalking, Dance Against the Wall, After the Bell, Hallelujah Time!, and High Tide – Ebb Tide. His poems have appeared in Prairie Schooner, American Life in Poetry, The New York Quarterly, Paterson Literary Review, The Cortland Review, Rattle, Tar River Poetry, Rust & Moth, Connecticut River Review, Hawk & Handsaw, and others. He teaches literature at Manchester Community College in Manchester, CT and he lives with his wife, Carol, in Coventry.

Humidity is fatigue, a scrim, that which holds the trees down by their shoulders or

shakes them, fills shadows with fat, bloats bark, prompts birdsong to echo, frogs to stillness

in warm shallows, and when rain comes, humid air breaks into pieces, and fills

each droplet with a tiny cloud.

John L. Stanizzi is author of the full-length collections Ecstasy Among Ghosts, Sleepwalking, Dance Against the Wall, After the Bell, Hallelujah Time!, and High Tide – Ebb Tide. His poems have appeared in Prairie Schooner, American Life in Poetry, The New York Quarterly, Paterson Literary Review, The Cortland Review, Rattle, Tar River Poetry, Rust & Moth, Connecticut River Review, Hawk & Handsaw, and others. He teaches literature at Manchester Community College in Manchester, CT and he lives with his wife, Carol, in Coventry.

Heikki Huotari 3 poems

Improbable Cause

An ill-fitting lid omits a crescent.

An improper moon rolls out

a pale green tentacle

on every board of every floor.

The visitor to earth asserts,

That's one bad axis of rotation

and one incidental anthropocene epoch.

Posing or not for Picasso,

posing or not as Picasso,

I have both eyes on one side

and the one quirk or cause I have

has probability no greater than point five.

So if birds do it both sides do it.

So to be a tow truck is

to be a tow truck being towed.

The submachine gun that you showed off

was no submachine gun

and it wasn't even loaded.

So the joke's on me.

An ill-fitting lid omits a crescent.

An improper moon rolls out

a pale green tentacle

on every board of every floor.

The visitor to earth asserts,

That's one bad axis of rotation

and one incidental anthropocene epoch.

Posing or not for Picasso,

posing or not as Picasso,

I have both eyes on one side

and the one quirk or cause I have

has probability no greater than point five.

So if birds do it both sides do it.

So to be a tow truck is

to be a tow truck being towed.

The submachine gun that you showed off

was no submachine gun

and it wasn't even loaded.

So the joke's on me.

Like Most Canadians

I'm nowhere near the freeway now,

where rattlesnakes are disciplined

and illustrating electronic books,

but through an atmospheric shortcut

of some kind, the music of the cylinders

of engine-breaking tractor-trailers is conveyed.

Like most Canadians,

I live within my boundaries and,

like most Canadians,

I'm bounded only on one side.

Now with your xray vision you can

see in me the metal object I absorbed.

Scaffold and Mirage

When you enter my implied icosahedron

resurrecting every which way

and have handsome antlers,

what some synesthetics see they won't believe,

as they've been fooled before. With nothing

to push off of you may only gyrate

and your higher powers say,

The law of gravity won't save you this time.

Palpable is palpable but every temporary structure

promises in its own underhanded way.

In a past century Heikki Huotari attended a one-room school and spent summers on a forest-fire lookout tower, is now a retired math professor, and has published three chapbooks, one of which won the Gambling The Aisle prize, and one collection, Fractal Idyll (A..P Press). Another collection is in press.

When you enter my implied icosahedron

resurrecting every which way

and have handsome antlers,

what some synesthetics see they won't believe,

as they've been fooled before. With nothing

to push off of you may only gyrate

and your higher powers say,

The law of gravity won't save you this time.

Palpable is palpable but every temporary structure

promises in its own underhanded way.

In a past century Heikki Huotari attended a one-room school and spent summers on a forest-fire lookout tower, is now a retired math professor, and has published three chapbooks, one of which won the Gambling The Aisle prize, and one collection, Fractal Idyll (A..P Press). Another collection is in press.

Peycho Kanev

Prone to Repetition

The stone

is a drum that works poorly,

the snake sleeping on it

and under the scorching sun

knows that,

but that is only

for a fraction of a second

and then again it turns into

a mirror

and the serpent sees itself

sinking into it and into the million

years of evolution

just to return to star dust again.

The man

stepping out of the house,

doesn’t know anything,

he just lights a cigarette and looks

at his reflection

in the last remaining rain puddle,

and thinks,

Oh not again.

Peycho Kanev is the author of four poetry collections and three chapbooks, published in the USA and Europe. His poems have appeared in many literary magazines, such as: Rattle, Poetry Quarterly, Evergreen Review, Front Porch Review, Hawaii Review, Barrow Street, Sheepshead Review, Off the Coast, The Adirondack Review, Sierra Nevada Review, The Cleveland Review and many others. His new chapbook titled Under Half-Empty Heaven was published in 2018 by Grey Book Press.

The stone

is a drum that works poorly,

the snake sleeping on it

and under the scorching sun

knows that,

but that is only

for a fraction of a second

and then again it turns into

a mirror

and the serpent sees itself

sinking into it and into the million

years of evolution

just to return to star dust again.

The man

stepping out of the house,

doesn’t know anything,

he just lights a cigarette and looks

at his reflection

in the last remaining rain puddle,

and thinks,

Oh not again.

Peycho Kanev is the author of four poetry collections and three chapbooks, published in the USA and Europe. His poems have appeared in many literary magazines, such as: Rattle, Poetry Quarterly, Evergreen Review, Front Porch Review, Hawaii Review, Barrow Street, Sheepshead Review, Off the Coast, The Adirondack Review, Sierra Nevada Review, The Cleveland Review and many others. His new chapbook titled Under Half-Empty Heaven was published in 2018 by Grey Book Press.