Excerpts from Omar Pimienta's Album of Fences

Translated by Jose Antonio Villarán

with review by Arturo Desimone

Translated by Jose Antonio Villarán

with review by Arturo Desimone

With gratitude to friend of the Journal, Arturo Desimone, for bringing Omar Pimienta's book to our attention.

|

from Section 2: L A I N V A S I Ó N P A U L A T I N A

|

from Section 2: T H E G R A D U A L I N V A S I O N

|

|

5.

Tenemos un hermoso mar de mierda gente parada perpendicular a la orilla vigilando un muro a la espera de un cambio de turno un tsunami que nos arrastre hasta San Diego un mar de mierda al que desemboca la ciudad entera cuando llega el niño y nos llora por días y noches tenemos casas de cartón que flotan hasta el mar un mar de mierda nuestra mierda y la de ellos y la de otros del cual alguna vez me sacó de las greñas el fantasma de mi madre un mar de mierda californiano Pacífico frío la mayoría del tiempo aunque parezca raro que la mierda pueda ser fría mar delator con olas de fósforo que ilumina los cuerpos por las noches mar que traga y escupe una cuchilla que bifurca su lengua un mar de mierda que presume su ciudadanía cruza los postes y se regresa arena que diluye los nombres de todos los que vemos el horizonte con las narices tapadas al filo de la primera frontera. |

5.

We have a beautiful sea of shit people standing perpendicular to the shore guarding a wall awaiting the next shift a tsunami to drag us to San Diego a sea of shit that the whole city flows into when el niño comes and cries day and night we have cardboard houses that float down to the sea a sea of shit our shit and their shit and the shit of others from which my mother’s ghost once pulled me by the hair a sea of shit californian Pacific cold most of the time though it might seem strange that shit can be cold a snitch ocean with phosphorous waves that lights the bodies at night sea that swallows and spits a knife that cuts its tongue a sea of shit that presumes its citizenry crosses the posts and comes back sand that dilutes the names of all those who see the horizon with our noses covered at the edge of the first border. |

|

6.

Esto no es una mentira no es una mentira acerca de la mentira una mentira que prolonga la mentira esto es la verdad la única verdad Anastasio Hernández-Rojas (San Luis Potosí 1968-San Diego †2010) se robó una botella de vino una botella de vino para celebrar el día de las madres la propia la de sus hijos cárcel y deportación golpes y electricidad la única verdad es muerte se puede ver se puede oír la mentira se propaga hasta crear un discurso pero la verdad es ésta: la gente muere y la verdad más real es ésta: hay gente que muere a manos de otra gente que cree que matar es parte de su oficio Anastasio Hernández -Rojas (San Luis Potosí 1968-San Diego †2010) gritó que lo dejaran de golpear lo golpeaban para que dejara de gritar la gente lo escuchó la gente lo escuchó aunque no quería escucharlo el sonido es más terco que la imagen es el ojo más miedoso que el oído la verdad al igual que el miedo se siente pocos pudieron traducir el grito otros gritaron que lo dejaran alguien pidió como él ayuda otros quisieron ignorar y cruzaron la frontera esto no es una mentira no es una mentira acerca de la mentira esto es la verdad la última verdad |

6.

This is not a lie it’s not a lie about the lie a lie that prolongs the lie this is the truth the only truth Anastasio Hernández-Rojas (San Luis Potosí 1968-San Diego †2010) stole a bottle of wine a bottle of wine to celebrate Mother’s Day his own mother his children’s prison and deportation beatings and electricity the only truth is death it can be seen it can be heard the lie spreads until it creates a discourse but the truth is this: people die and the most real truth is this: there are people who die at the hands of others who believe killing is part of their job Anastasio Hernández-Rojas (San Luis Potosí 1968-San Diego †2010) screamed so they would stop beating him they beat him to make him stop screaming the people heard the people heard even though they didn’t want to sound is more stubborn than image the eye is more afraid than the ear the truth just like fear is felt few were able to translate the scream others screamed at them to let him go someone asked like him for help others tried to ignore this and crossed the border this is not a lie it’s not a lie about the lie this is the truth the last truth. |

ALBUM OF FENCES - BOOK REVIEW

By Arturo Desimone

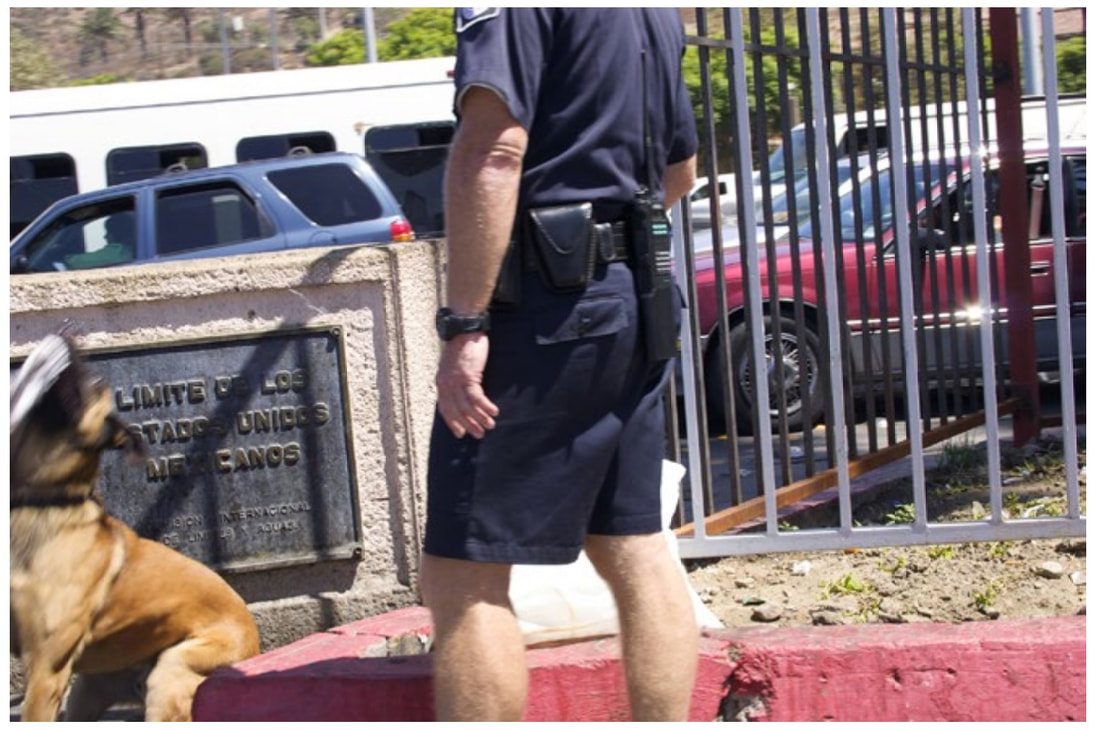

Omar Pimienta's Album of Fences is precisely this—part photo-album, part bilingual poetry book, (English translation by José Villarán) with a photography exhibition. Nowhere as ominous as the title implies—though it refers to the fences along the US Mexico border, increasingly militarized, returning to its historical state of war-zone—the fences also refer to the vocation of Pimienta’s father Don Marcos, a blacksmith artisan with only nine fingers, who is rendered as a character with more presence than any other in the book. The absence of a finger lost while working to support the family is a silence that speaks, and makes the authority of the father.

The translator conveys el habla de sus manos literally, as ''the talk of his hands'' in one of the poems about the father. Here, as in a few other places in this translation, certain figures of speech might have perhaps been rendered less materially or less literally--el habla for example, can be understood as ''the parlance (of his hands)'' The poetry in figures of speech commonly used in Spanish could, ideally, have been brought to the fullest attention of the Anglo reader, though that might come at the cost of simplicity. Translator José Antonio Villarán takes some liberties in translation, yet effectively preserves the endearing Don Marcos and his son.

The finger’s absence, on hands that form part of a man's speech and language, transforms from mere absence into a poetic silence wielding more power than words. Poetry uses words in an arc contrary to chatter—as materials that summon music from silence, to transport us back to places of stillness: a silence that is not absence, and surges beyond the merely meditative; a silence that talks…like the missing finger of the old man with an alias.

One of the poems tells of Pimienta’s father Don Marcos's adoption of a false identity, explores the subject of what happens to us as the consequence of using aliases and alibis. To cross the border, Marcos adopts the name of US citizen Prisciliano Gil Bautista, born in Indiana. In a chilling interrogation-dialogue within the verse, US immigrations officer Cruz reveals he knows the name belonged to a Prisciliano who already died in Tijuana.

What is the power in names? Does an alibi grant us that power of invisibility at no expense? Or does it possess us, inhabiting the user, rather than simply allowing the impostor to inhabit the alibi?

Pimienta says donning the name gave his father a “social organ” made of papel picado, a form of decorative papier maché used in Mexico for masks and ornamentations. Like much literature on the immigrant minority experience, the poet is brought to a new self-consciousness of certain antics that would otherwise go unnoticed—for example, a father who talks with his hands. Without having immigrated to the North, would we even notice that people somewhere do not talk with their hands? Do Argentinian and Mediterranean novelists, for example, speaking of their lands of origin, mention the peculiarity of their characters' gesticulating with their hands when it would seem redundant?

Pimienta, in the playfulness of childhood, despite having to work

with don Marcos in the blacksmith-shop, seems almost grateful to his father and employer, showing the workshop as the place where he and other youths found more than only a means to avail their families in Mexico: they also find creativity,

''in don Marcos' blacksmith shop we built:

a giant whale a sea snail some clouds

a flag (...)

a press to compress marijuana'' The availability of wielding tools cannot sever childhood's realm completely from the young laborers.

"time stretches and compresses in memory

this text depends on that elasticity ''

The last stanza quoted above, portrays a reality not only for autobiographical writing.

Recent pictures taken of Marcos' father recently have a more professional quality—Pimienta is a professional, widely-exhibited contemporary visual artist and poet—though the photos of Pimienta as a child, taken by his family, interact with poetry in a more touching manner.

Rather than a tale of the horrors of being an immigrant, or mere political confrontation of xenophobia—however necessary and natural in the current time of torture camps for border-crossers--Album of Fences tells a coming of age story, of a youth balanced on the border. Here, childhood and coming of age into adolescence and manhood are a healthy and sane development, thanks to his parents, though that sane life is confronted nonetheless at every turn of the Album with the unfettered insanity of border politics. In one verse, the child’s plastic American soldiers say ‘’made in China.”

Here and there we get a self-portrait in poetry that runs contrary to the expected—despite the dangers inherent in being an immigrant laborer's son, what we glimpse through the fence is a childhood refuged, at times, from the pain of class consciousness dawning too early. A childhood kept safe from destruction is what all good parents struggle provide. The Album provokes us to reflect on the interplay and tensions between forces of political alienation and a good, sane life; as well as the seeming contradiction between a stable upbringing and life on the road, constantly crossing a border, risking danger.

''Southbound to see older people

northbound to see younger people

(..) I grow when I travel

from those long and slow journeys

we always came back with something: boxes of grapes

(...) gallons of tequila

cheese, lots of cheese

amusement park tickets

One picture at first glance seems the conventional photo of a child

with someone costumed as a Disney animal in the heat of the fun-park. Later he reveals it's his cousin:

all my relatives up north worked in something fun

in the fields with food with Mickey ''

Pimienta's parents have not told their 8-year-old son that the Mexican 'Mickey'' might be exploited or underpaid, or that working the grape field is not much fun—but why should they? The album homages parents willing to lose fingers in order to preserve the priceless illusion of childhood.

Instead of the necropolis of migration-related trauma, we read of life: long treks with grapes, cheese and tequila, travelling, all despite being poor, and these earthly delights all accessed in the only ways that the poor can have them.

Yet, the awareness of what these delights mean, is always different:

I have a picture with a penguin

I have a picture with someone else's cousin''

Works like Pimienta's show that poetry, rather than being limited (even in the genre's political outpourings) to being ultimately a bit of bourgeois confessionalism, can also be a good bit of working-class confessionalism. Perhaps that's for the better.

While successfully depicting the alienation of the rhetoric around the border, Pimienta challenges popular notions of unlimited oppression being a basis for writing interesting poetry. Pimienta also challenges the more recent idea that all immigrants are case-studies in misery and ''the marginalized.’’ Pimienta’s book offers a refreshing turn, a break of sorts from other social-realism that has sprung up elsewhere in Latino literature in the smattering of journals accepting ‘’Latino’’ literary production.

Through the multifaceted album laced with photographic interstices with verses, the reader gets a sense of knowing Pimienta, as a child and young man in

the form of a coming of age story. Towards the end, Pimienta in college makes friends with bloggers and with Chicano Studies, and discovers parties in Tijuana and the US.

Quite surprisingly, the exploration of sex, usually an indelible part of the coming-of-age genre, plays almost no role in the later part of the book where Pimienta tells of his adolescence and young adulthood. It as if these developments fell absent or were omitted, (possibly following the advice of MFA thesis-supervisors?) This is one fault in the Album, making it less risk-taking, as it departs for no good reason from a phase in the dramatic arc of the literary tradition of coming-of-age tales. If skipped, then the artwork should allude as to why the absence. Possibly, to describe sexual awakenings of a young man goes against the current codes of the MFA programs. In the NY Times article ‘’Sex and the American Male Novelist’’ critic and highly-polemical provocateuse Katie Roiphe compares the sexual explorations of second-generation-immigrant writers like Philip Roth and Norman Mailer, to the glaring absence of sex, substituted by a preference for cuddles, to be found in Jonathan Franzen, David Foster-Wallace, Jonathan Saffran-Foer among other recent stars of the creative-writing program-bubble. Beyond the musings of a bête noir of sex and of literary critique, the absence triggers inquisitive readers of contemporary Latino-lit to ask another poignant question: is the sexual psyche of the Latino heterosexual male effaced from North American contemporary literature, and from wider popular culture for being too ‘’problematic’’? Does the current culture of erudite liberals who fathom themselves tolerant, actually tolerate any real, interesting exploration of the sexual experience of the working class Latino or Latina, other than the complete omission of it as too provocative or unsettling for the current university-literary bubble? Can the new immigrant writers not have the same freedom as previous immigrant writers of Mailer’s and Roth’s generation?

Certainly, to include such accounts in a photo-book that beyond any doubt will be read by the author’s family might have guaranteed embarrassment at the very least—though Junot Díaz among others have taken such risks.

The Album’s chapter titled “Gradual Invasion'' marks the entry of corrupt forces into Omar’s childhood world: the militarization of not only the border, but also of the mere conversation about the border and immigrants. This militarization does not limit itself to the rhetoric of sheriffs: it is also in the eventual classrooms where they will sit in silence hearing of Chicano Studies.

"we trained since we were children ... in the dust

ghost town facades remnants of the Titanic

fictitious scenes of what awaited us

we learned their customs on VHS '' goes some revealing verse, under a sentimental picture of a small boy in a desert yard. Childhood’s joys await the invasion of foolish politicians, law enforcement, the academics: all enemies of childhood. Pimienta here gives a good twist of irony, while sincere: for the child Omar, it is his world being invaded, taken over by people and things that clearly are alien trespassers in childhood’s kingdom. Much conventional wisdom would have us believe the foreign child is the invader. In this way, Pimienta forms a small part of a future narrative of immigrant children surviving the contemporary madness, who one day will ask: who was the real invader? Who invaded the world of children—in the name of political blather, kafkaesque legislation, and endless discussions about migration on the right and left?

The pictures of the child and father, inevitably touching, complement the mostly short, clear poems. Those with an intermediate command of Spanish can benefit from useful bilingual formatting of the book, putting original and translation side by side, so as to enjoy both. Let's hope for more bilingual editions, in what are and remain the two major languages of the United States.

By Arturo Desimone

Omar Pimienta's Album of Fences is precisely this—part photo-album, part bilingual poetry book, (English translation by José Villarán) with a photography exhibition. Nowhere as ominous as the title implies—though it refers to the fences along the US Mexico border, increasingly militarized, returning to its historical state of war-zone—the fences also refer to the vocation of Pimienta’s father Don Marcos, a blacksmith artisan with only nine fingers, who is rendered as a character with more presence than any other in the book. The absence of a finger lost while working to support the family is a silence that speaks, and makes the authority of the father.

The translator conveys el habla de sus manos literally, as ''the talk of his hands'' in one of the poems about the father. Here, as in a few other places in this translation, certain figures of speech might have perhaps been rendered less materially or less literally--el habla for example, can be understood as ''the parlance (of his hands)'' The poetry in figures of speech commonly used in Spanish could, ideally, have been brought to the fullest attention of the Anglo reader, though that might come at the cost of simplicity. Translator José Antonio Villarán takes some liberties in translation, yet effectively preserves the endearing Don Marcos and his son.

The finger’s absence, on hands that form part of a man's speech and language, transforms from mere absence into a poetic silence wielding more power than words. Poetry uses words in an arc contrary to chatter—as materials that summon music from silence, to transport us back to places of stillness: a silence that is not absence, and surges beyond the merely meditative; a silence that talks…like the missing finger of the old man with an alias.

One of the poems tells of Pimienta’s father Don Marcos's adoption of a false identity, explores the subject of what happens to us as the consequence of using aliases and alibis. To cross the border, Marcos adopts the name of US citizen Prisciliano Gil Bautista, born in Indiana. In a chilling interrogation-dialogue within the verse, US immigrations officer Cruz reveals he knows the name belonged to a Prisciliano who already died in Tijuana.

What is the power in names? Does an alibi grant us that power of invisibility at no expense? Or does it possess us, inhabiting the user, rather than simply allowing the impostor to inhabit the alibi?

Pimienta says donning the name gave his father a “social organ” made of papel picado, a form of decorative papier maché used in Mexico for masks and ornamentations. Like much literature on the immigrant minority experience, the poet is brought to a new self-consciousness of certain antics that would otherwise go unnoticed—for example, a father who talks with his hands. Without having immigrated to the North, would we even notice that people somewhere do not talk with their hands? Do Argentinian and Mediterranean novelists, for example, speaking of their lands of origin, mention the peculiarity of their characters' gesticulating with their hands when it would seem redundant?

Pimienta, in the playfulness of childhood, despite having to work

with don Marcos in the blacksmith-shop, seems almost grateful to his father and employer, showing the workshop as the place where he and other youths found more than only a means to avail their families in Mexico: they also find creativity,

''in don Marcos' blacksmith shop we built:

a giant whale a sea snail some clouds

a flag (...)

a press to compress marijuana'' The availability of wielding tools cannot sever childhood's realm completely from the young laborers.

"time stretches and compresses in memory

this text depends on that elasticity ''

The last stanza quoted above, portrays a reality not only for autobiographical writing.

Recent pictures taken of Marcos' father recently have a more professional quality—Pimienta is a professional, widely-exhibited contemporary visual artist and poet—though the photos of Pimienta as a child, taken by his family, interact with poetry in a more touching manner.

Rather than a tale of the horrors of being an immigrant, or mere political confrontation of xenophobia—however necessary and natural in the current time of torture camps for border-crossers--Album of Fences tells a coming of age story, of a youth balanced on the border. Here, childhood and coming of age into adolescence and manhood are a healthy and sane development, thanks to his parents, though that sane life is confronted nonetheless at every turn of the Album with the unfettered insanity of border politics. In one verse, the child’s plastic American soldiers say ‘’made in China.”

Here and there we get a self-portrait in poetry that runs contrary to the expected—despite the dangers inherent in being an immigrant laborer's son, what we glimpse through the fence is a childhood refuged, at times, from the pain of class consciousness dawning too early. A childhood kept safe from destruction is what all good parents struggle provide. The Album provokes us to reflect on the interplay and tensions between forces of political alienation and a good, sane life; as well as the seeming contradiction between a stable upbringing and life on the road, constantly crossing a border, risking danger.

''Southbound to see older people

northbound to see younger people

(..) I grow when I travel

from those long and slow journeys

we always came back with something: boxes of grapes

(...) gallons of tequila

cheese, lots of cheese

amusement park tickets

One picture at first glance seems the conventional photo of a child

with someone costumed as a Disney animal in the heat of the fun-park. Later he reveals it's his cousin:

all my relatives up north worked in something fun

in the fields with food with Mickey ''

Pimienta's parents have not told their 8-year-old son that the Mexican 'Mickey'' might be exploited or underpaid, or that working the grape field is not much fun—but why should they? The album homages parents willing to lose fingers in order to preserve the priceless illusion of childhood.

Instead of the necropolis of migration-related trauma, we read of life: long treks with grapes, cheese and tequila, travelling, all despite being poor, and these earthly delights all accessed in the only ways that the poor can have them.

Yet, the awareness of what these delights mean, is always different:

I have a picture with a penguin

I have a picture with someone else's cousin''

Works like Pimienta's show that poetry, rather than being limited (even in the genre's political outpourings) to being ultimately a bit of bourgeois confessionalism, can also be a good bit of working-class confessionalism. Perhaps that's for the better.

While successfully depicting the alienation of the rhetoric around the border, Pimienta challenges popular notions of unlimited oppression being a basis for writing interesting poetry. Pimienta also challenges the more recent idea that all immigrants are case-studies in misery and ''the marginalized.’’ Pimienta’s book offers a refreshing turn, a break of sorts from other social-realism that has sprung up elsewhere in Latino literature in the smattering of journals accepting ‘’Latino’’ literary production.

Through the multifaceted album laced with photographic interstices with verses, the reader gets a sense of knowing Pimienta, as a child and young man in

the form of a coming of age story. Towards the end, Pimienta in college makes friends with bloggers and with Chicano Studies, and discovers parties in Tijuana and the US.

Quite surprisingly, the exploration of sex, usually an indelible part of the coming-of-age genre, plays almost no role in the later part of the book where Pimienta tells of his adolescence and young adulthood. It as if these developments fell absent or were omitted, (possibly following the advice of MFA thesis-supervisors?) This is one fault in the Album, making it less risk-taking, as it departs for no good reason from a phase in the dramatic arc of the literary tradition of coming-of-age tales. If skipped, then the artwork should allude as to why the absence. Possibly, to describe sexual awakenings of a young man goes against the current codes of the MFA programs. In the NY Times article ‘’Sex and the American Male Novelist’’ critic and highly-polemical provocateuse Katie Roiphe compares the sexual explorations of second-generation-immigrant writers like Philip Roth and Norman Mailer, to the glaring absence of sex, substituted by a preference for cuddles, to be found in Jonathan Franzen, David Foster-Wallace, Jonathan Saffran-Foer among other recent stars of the creative-writing program-bubble. Beyond the musings of a bête noir of sex and of literary critique, the absence triggers inquisitive readers of contemporary Latino-lit to ask another poignant question: is the sexual psyche of the Latino heterosexual male effaced from North American contemporary literature, and from wider popular culture for being too ‘’problematic’’? Does the current culture of erudite liberals who fathom themselves tolerant, actually tolerate any real, interesting exploration of the sexual experience of the working class Latino or Latina, other than the complete omission of it as too provocative or unsettling for the current university-literary bubble? Can the new immigrant writers not have the same freedom as previous immigrant writers of Mailer’s and Roth’s generation?

Certainly, to include such accounts in a photo-book that beyond any doubt will be read by the author’s family might have guaranteed embarrassment at the very least—though Junot Díaz among others have taken such risks.

The Album’s chapter titled “Gradual Invasion'' marks the entry of corrupt forces into Omar’s childhood world: the militarization of not only the border, but also of the mere conversation about the border and immigrants. This militarization does not limit itself to the rhetoric of sheriffs: it is also in the eventual classrooms where they will sit in silence hearing of Chicano Studies.

"we trained since we were children ... in the dust

ghost town facades remnants of the Titanic

fictitious scenes of what awaited us

we learned their customs on VHS '' goes some revealing verse, under a sentimental picture of a small boy in a desert yard. Childhood’s joys await the invasion of foolish politicians, law enforcement, the academics: all enemies of childhood. Pimienta here gives a good twist of irony, while sincere: for the child Omar, it is his world being invaded, taken over by people and things that clearly are alien trespassers in childhood’s kingdom. Much conventional wisdom would have us believe the foreign child is the invader. In this way, Pimienta forms a small part of a future narrative of immigrant children surviving the contemporary madness, who one day will ask: who was the real invader? Who invaded the world of children—in the name of political blather, kafkaesque legislation, and endless discussions about migration on the right and left?

The pictures of the child and father, inevitably touching, complement the mostly short, clear poems. Those with an intermediate command of Spanish can benefit from useful bilingual formatting of the book, putting original and translation side by side, so as to enjoy both. Let's hope for more bilingual editions, in what are and remain the two major languages of the United States.

A B O U T T H E A U T H O R

Omar Pimienta is an interdisciplinary artist and writer who lives and works in the San Diego / Tijuana border region. His artistic practice examines questions of identity, migration, citizenship, emergency poetics, landscape and memory. His work has been presented in museums and cultural centers of the U.S., Mexico, Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Denmark, Germany, Morocco, and Spain. He has published four books of poetry: Primera Persona Ella (La Linea/Anortecer 2004); La Libertad: Ciudad de paso (awarded the 2006 CONACULTA / CECUT Publication Prize); Escribo desde Aquí (Pre-Textos 2009, awarded the Emilio Prado 10th International Publication Prize from the Centro Cultural Generación del 27 Malaga Spain in 2009); and his most recent book, Álbum de las rejas, (Liliputienses 2016). He is currently a PhD candidate in Literature at the University of California, San Diego, and he received his MFA in Visual Arts from the same institution.

Omar Pimienta is an interdisciplinary artist and writer who lives and works in the San Diego / Tijuana border region. His artistic practice examines questions of identity, migration, citizenship, emergency poetics, landscape and memory. His work has been presented in museums and cultural centers of the U.S., Mexico, Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Denmark, Germany, Morocco, and Spain. He has published four books of poetry: Primera Persona Ella (La Linea/Anortecer 2004); La Libertad: Ciudad de paso (awarded the 2006 CONACULTA / CECUT Publication Prize); Escribo desde Aquí (Pre-Textos 2009, awarded the Emilio Prado 10th International Publication Prize from the Centro Cultural Generación del 27 Malaga Spain in 2009); and his most recent book, Álbum de las rejas, (Liliputienses 2016). He is currently a PhD candidate in Literature at the University of California, San Diego, and he received his MFA in Visual Arts from the same institution.

A B O U T T H E T R A N S L A T O R

Jose Antonio Villarán is the author of la distancia es siempre la misma (Matalamanga, 2006) and el cerrajero / the locksmith (AUB, 2012). In 2008 he created the AMLT project, an exploration of hypertext literature and collective authorship; the project was sponsored by Puma from 2011-2014. His third book, titled open pit, is forthcoming from AUB (Lima) in 2018. He holds an MFA in Writing from the University of California-San Diego, and is currently a PhD student of Literature at the University of California-Santa Cruz. His translations have been published in Entropy Magazine, Boom, California, Tripwire, and Deluge.

Jose Antonio Villarán is the author of la distancia es siempre la misma (Matalamanga, 2006) and el cerrajero / the locksmith (AUB, 2012). In 2008 he created the AMLT project, an exploration of hypertext literature and collective authorship; the project was sponsored by Puma from 2011-2014. His third book, titled open pit, is forthcoming from AUB (Lima) in 2018. He holds an MFA in Writing from the University of California-San Diego, and is currently a PhD student of Literature at the University of California-Santa Cruz. His translations have been published in Entropy Magazine, Boom, California, Tripwire, and Deluge.

ABOUT THE BOOK

Originally pubished in 2016 as Álbum de las rejas, (Liliputienses 2016), then published in 2018 in side by side translation as Album of Fences by Cardboard House Press https://cardboardhousepress.org/ Album of Fences was supported by a grant from Arizona Humanities.

Originally pubished in 2016 as Álbum de las rejas, (Liliputienses 2016), then published in 2018 in side by side translation as Album of Fences by Cardboard House Press https://cardboardhousepress.org/ Album of Fences was supported by a grant from Arizona Humanities.

Arturo Desimone, Arubian-Argentinian writer and visual artist, was born in 1984 on the island Aruba. At the age of 22 he emigrated to the Netherlands. He is currently based in Argentina (a country two of his ancestors left during the 1970s) while working on a long fiction project about childhoods, diasporas, islands and religion. Desimone’s articles, poetry and short fiction pieces have appeared in CounterPunch, Círculo de Poesía, Acentos Review, New Orleans Review, Democracia Abierta, BIM Magazine. He writes a monthly blog on movements in Latin American poetry for Drunken Boat, ''Notes on a Return to the Ever-Dying Lands''. https://arturoblogito.wordpress.com/